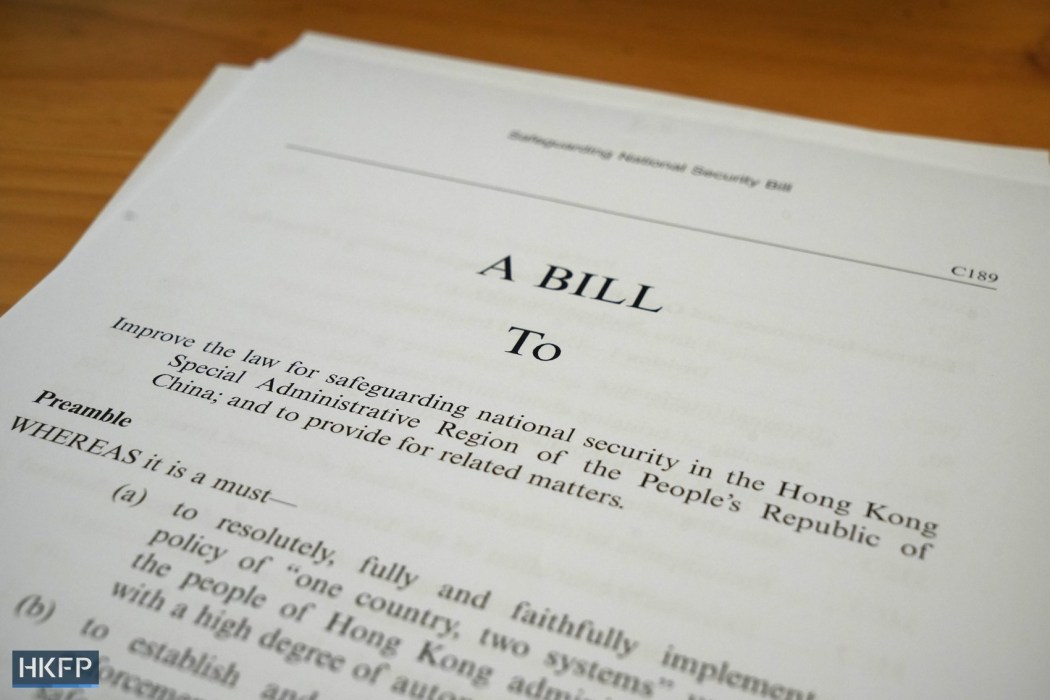

Hong Kong’s new, homegrown security law does not undermine press freedom, the city’s justice secretary has stated, amid concern that legislation against external interference and theft of state secrets may affect reporting.

In an opinion piece published in Ming Pao on Monday, Secretary for Justice Paul Lam said Article 23 would not have any “unreasonable restrictions” on the work of the media. Criticism against the government was allowed “no matter how sharp or severe,” he added.

“As long as the media industry adheres to the professional principles of truth-seeking, fairness, objectivity, impartiality and being comprehensive… there is no need to be especially worried about breaching the law,” Lam wrote in Chinese.

The justice secretary’s comments came about a month after authorities fast-tracked a new locally-legislated security law through the Legislative Council, which lost its effective opposition after sweeping electoral changes in 2021 allowing only those deemed “patriots” to be elected.

Known colloquially as Article 23, the security law targets treason, insurrection, sabotage, external interference, sedition, theft of state secrets and espionage. It allows for pre-charge detention of to up to 16 days, and suspects’ access to lawyers may be restricted, with penalties involving up to life in prison. Arrests have yet to be made under the legislation.

The law is separate from the Beijing-imposed national security legislation, which was enacted after the protests and unrest of 2019.

The Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) has expressed concern that Article 23 could see reporters falling afoul of the law, citing “vague” provisions relating to offences such as external interference and theft of state secrets.

Last week, Chief Executive John Lee suggested that the city had no plans to enact a “fake news law,” after authorities first raised the proposal in 2021. His comments came after Lam said in an interview that authorities were not considering criminalising “fake news” as it was hard to define, adding that Article 23 had already partly helped tackle the issue.

Press freedom

In the Ming Pao op-ed, Lam said the new homegrown security law had improved the city’s laws that safeguard national security while also respecting “basic human rights and freedoms.” It came less than three weeks after a press freedom advocate from NGO Reporters Without Borders was barred from entering the city.

Lam added that the government works hand in hand with the media to bring about change in society.

It is despite government departments thwarting access to the press seeking to tell even positive stories of the city.

“The government hopes and needs the media industry’s help to convey accurate, fair and positive messages,” Lam wrote. “But more so, it needs to understand citizens’ thoughts and needs through the media.”

Hong Kong has plummeted in international press freedom indices since the onset of the security law. Watchdogs cite the arrest of journalists, raids on newsrooms and the closure of around 10 media outlets including Apple Daily, Stand News and Citizen News. Over 1,000 journalists have lost their jobs, whilst many have emigrated. Meanwhile, the city’s government-funded broadcaster RTHK has adopted new editorial guidelines, purged its archives and axed news and satirical shows.

See also: Explainer: Hong Kong’s press freedom under the national security law

In 2022, Chief Executive John Lee said press freedom was “in the pocket” of Hongkongers but “nobody is above the law.” Although he has told the press to “tell a good Hong Kong story,” government departments have been reluctant to respond to story pitches.

In February, ahead of the passing of the homegrown security law, a HKJA survey of reporters found that all 160 respondents said they believed Article 23 would have a “negative impact” on press freedom in Hong Kong, with 90 per cent of them saying the impact would be “significant.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team