Hong Kong democracy has taken a “quantum leap forward,” officials have told a UN rights committee, during a grilling over the national security law, declining press freedom and other developments in the wake of the 2019 protests.

Leading a nine-member delegation of government officers, Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang evaded the panel’s questions about shrinking political participation, saying only that the electoral overhaul ensuring only “patriots” can run for office had “enhanced the effectiveness of governance.”

“In fact, democracy has taken a quantum leap forward since the return to the motherland in 1997,” Tsang said at the Tuesday session with the UN Human Rights Committee.

The two-and-a-half-hour session capped three days of meetings with the committee, which is tasked with monitoring state parties’ commitments to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

According to the UN, state parties must report on the progress made towards adopting measures relating to the covenant every four years, after which a meeting is convened.

Civil society organisations were invited to submit issues for discussion. NGOs including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch were among the groups that provided reports, while Hong Kong-based groups Justice Centre Hong Kong and the Society for Community Organisation made their submissions in an earlier round two years ago. Pro-democracy party Civic Party, as well as the now-defunct Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions and Demosisto, also took part – with the latter groups having made submissions before they disbanded.

Despite repeated questioning, the delegates did not provide a direct answer as to whether participating organisations would face legal consequences.

The Hong Kong delegation, which included representatives from the Security Bureau, the Police Force, the Department of Justice, the Labour Department and the Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, attended the sessions in Switzerland virtually. Tuesday’s meeting followed a session on Friday that was cut short by technical difficulties.

Freedoms restricted

The three days of meetings covered a broad swathe of rights issues in Hong Kong, from the mechanism used to screen asylum seekers to the treatment of the city’s 340,000 domestic workers.

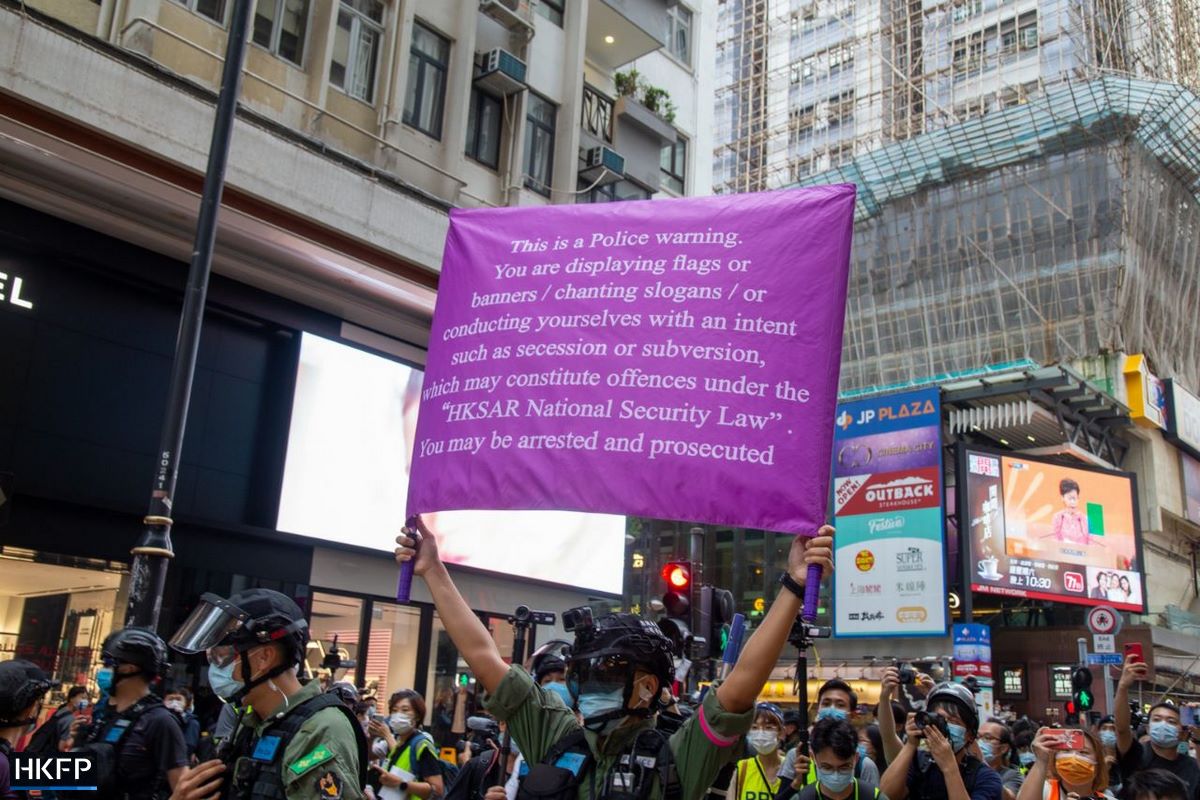

Friday’s questions, however, focused almost entirely on political developments following the passing of the 2020 national security law.

Tania Maria Abdo Rochelle, a member of the committee representing Paraguay, raised concerns about declining press freedom, including allegedly censorship at the government-owned broadcaster RTHK, the arrests of the now-defunct Apple Daily and Stand News staff, and the practice of barring reporters from accessing public records.

“Is the state considering lifting the administrative measures which restrict the capacity and operations of media? Does the state plan to restore the editorial independence of Radio Television Hong Kong?” she asked.

Abdo Rochell then questioned the state of academic freedom in Hong Kong, describing university authorities’ sanctions on student unions. She also mentioned by name Allan Au, a consultant with the Chinese University’s journalism school arrested by national security police in April, as well as pro-democracy activist and law professor Benny Tai, who was fired by the University of Hong Kong in 2020 for alleged misconduct.

“Does Hong Kong envision taking action to restore freedom of thought and expression in the academic sphere?” the expert asked.

Shuichi Furuya, vice-chair of the committee, pressed the delegation on the government’s use of Covid-19 social distancing rules to bar protests. Applications to hold the annual Tiananmen crackdown vigil and July 1 democracy march were shot down in 2020 and 2021, with authorities pointing to the pandemic.

The expert cited the example of police fining three people who took part in a protest in support of Ukraine in March.

“How [does] the Hong Kong government make the anti-pandemic restrictive measures compatible with the right of peaceful assembly?” Furuya asked, adding that the restrictions had imposed “undue restriction” on such gatherings.

In response, Deputy Secretary for Security Shirley Yung said the allegation that the government uses social distancing measures to suppress assemblies is “merely unfounded” and based on “speculation.”

Democratic progress in ‘opposite direction’

Experts also raised concerns over the fate of labour unions and other civil society groups disbanding under the pressure of the national security law.

“In the less-than-two-years since the national security law was enacted, nearly 100 civil society organisations operating in Hong Kong have had either to disband or to relocate,” said Carlos Gomez Martinez, adding that groups were reportedly facing “increasing difficulties in carrying out” activities.

The expert asked the delegation to provide “information on steps taken” to ensure that the enforcement of the security law, and the Societies Ordinance, does not violate rights to association.

Delegate Apolonnia Liu, Deputy Secretary for Security, said in response that civil society groups’ decisions to “remain or leave Hong Kong… are based on different factors.”

“On the other hand, we should point out that the implementation of the national security law has actually reverted the chaotic situation and serious violence earlier and restored stability,” she added.

Christopher Arif Bulkan, vice-chair of the committee, highlighted the electoral overhaul last year, which decreased democratic representation in the Legislative Council.

“The rights of Hong Kong residents have gone in the opposite direction” since the last UN review of the city in 2018, he said, adding that the number of directly elected seats in the legislature has fallen and that candidates must be pre-screened.

“The bottom line is that 4.5 million voters in Hong Kong can elect only 20 of 90 legislators,” he said, adding that the remainder are chosen by a “tiny, unrepresentative body” dominated by special interests.

Bulkan also asked when Hong Kong would implement universal suffrage and what the “obstacle” was towards allowing the public wider access to voting and participating in political life.

In response, Tsang said: “[P]lease be rest assured that the ultimate aim of attaining universal suffrage… remains unchanged.”

Last March, the Hong Kong government said in a press release that “certain rights and freedoms recognised in the ICCPR are not absolute: the ICCPR stipulates that certain rights and freedoms may be subject to restrictions as prescribed by law if it is necessary in the interests of national security, public safety, public order or the rights and freedoms of others, etc.”

The Hong Kong delegates and the rights committee will meet for a closing session on July 22, during which the committee will make recommendations for the city’s consideration.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team