Officially, July 1 marks the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule in 1997. Traditionally, it was also a day for tens – or even hundreds – of thousands of Hongkongers to take their diverse demands and grievances to the streets.

From pro-democracy groups to labour unions, from LGBT+ rights advocates to artists wielding satirical effigies, the July 1 march was the most important date on the annual protest calendar. It served as a fundraiser for dozens of NGOs, was testimony to Hong Kong’s thriving civil society, and acted a barometer for free speech. For years, the government vowed to listen to the public’s views “in a humble manner,” saying it “respected people’s rights to take part in processions and their freedom of expression.”

But over the last two years, the colourful annual procession was banned by the police citing public health concerns during the Covid-19 pandemic. More notably, the long-time organiser of the march – the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF) – and many participating groups, were dissolved after the Beijing-imposed national security law came into force a little over two years ago.

As the city celebrates 25 years since the Handover, HKFP revisits the demands made by Hongkongers and how the local political landscape has changed over the years.

2003: Anti-Article 23; ‘Don’t want Tung Chee-hwa’

Between 1997, when Hong Kong was returned to China, and 2002, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China had organised marches on July 1. The group disbanded last September and is currently facing subversion charges under the security law.

But the notable turnout in 2003 – when some 530,000 Hongkongers filled the streets to oppose the enactment of a security law – left many believing the iconic march only began that year. The new organisers – the CHRF – emerged as a prominent protest coalition in the years that followed.

Dissatisfaction with the government, under the leadership of Tung Chee-hwa, had reached a tipping point when the authorities announced plans in September 2002 to pass Article 23 of the Basic Law, which would allow it to enact laws against treason, secession, sedition and other national security offences. It sparked fears among pro-democracy activists that civil liberties could be negatively threatened.

Together with economic recession in the aftermath of the SARS epidemic, CHRF estimated that over half a million people joined its march, with many calling for Article 23 to be axed and for Tung to step down. Some held protest slogans printed by the pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily, which also folded in June 2021 following national security arrests of senior staff and a raid on its newsroom.

Police estimated at least 350,00 people had participated in the march, local media reported at the time. Over a year later, Tung resigned.

2004: ‘Fight for universal suffrage in 2007, 2008’

One year after the historic 2003 rally, the turnout for the 2004 demonstration was estimated to be even higher by organisers, who said some 530,000 people hit the streets. But the figure was disputed by scholars, with some saying only around 400,000 turned up. The Public Opinion Programme at the University of Hong Kong (HKUPOP) also gave a much lower estimate of 193,500, while police said 200,000 people attended.

Demonstrators urged the government to implement universal suffrage – as promised in the mini-constitution – by 2007 and 2008, urging the authorities to give eligible voters a say in electing the chief executive and all legislative seats.

2005: ‘Oppose collusion between government and businesses, fight for full universal suffrage’

The CHRF saw a sharp drop in the number of marchers who joined them in 2005 when they repeated their demand for full universal suffrage. Around 20,000 showed up, the organisers said, while police put the turnout at around 11,000.

2006: ‘Equal and just New Hong Kong, democratic universal suffrage creates hope’

In 2006, the CHRF’s demands focused on equality and justice, as the turnout bounced back slightly to around 58,000, they estimated. HKUPOP and police figures were 36,000 and 28,000, respectively.

2007: ‘Fight for universal suffrage, improve livelihood’

On the 10th anniversary of Hong Kong’s Handover from Britain, around 68,000 people took to the streets and once again asked the government to introduce full democracy, organisers said. Marchers also called on the authorities to improve their livelihoods. Some activists, including then-lawmaker Leung Kwok-hung, burned an invitation card to attend the Handover celebrations.

The government said only 20,000 took part in the procession, while HKUPOP said 32,000 showed up.

2008: ‘One dream, one human right; Return power to the people, improve livelihood’

The July 1 demonstration turnout dipped again in 2008, around a month before Beijing held the Summer Olympic Games. Positive sentiment towards the mainland was high, though around 47,000 people marched on the day, organisers said. Police and HKUPOP gave similar estimates of between 15,500 and 17,500.

The CHRF’s demands were a twist on the Beijing Olympics slogan “One World, One Dream.” The activist group called for attention on human rights issues in Hong Kong, and for power to be returned to the people.

2009: ‘Wrong policymaking, wealth disparity, return the power to the people, improve livelihood’

More people joined the July 1 march in 2009 compared to the year before, as the CHRF said 76,000 participated. Again, HKUPOP and the government had similar counts of 31,000 and 28,000 attendees, respectively.

2010: ‘Go forward on July 1, the future of Hong Kong is in my hands’

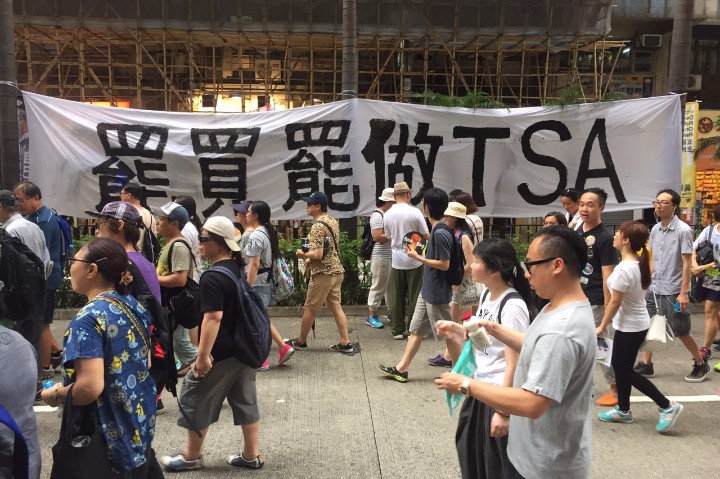

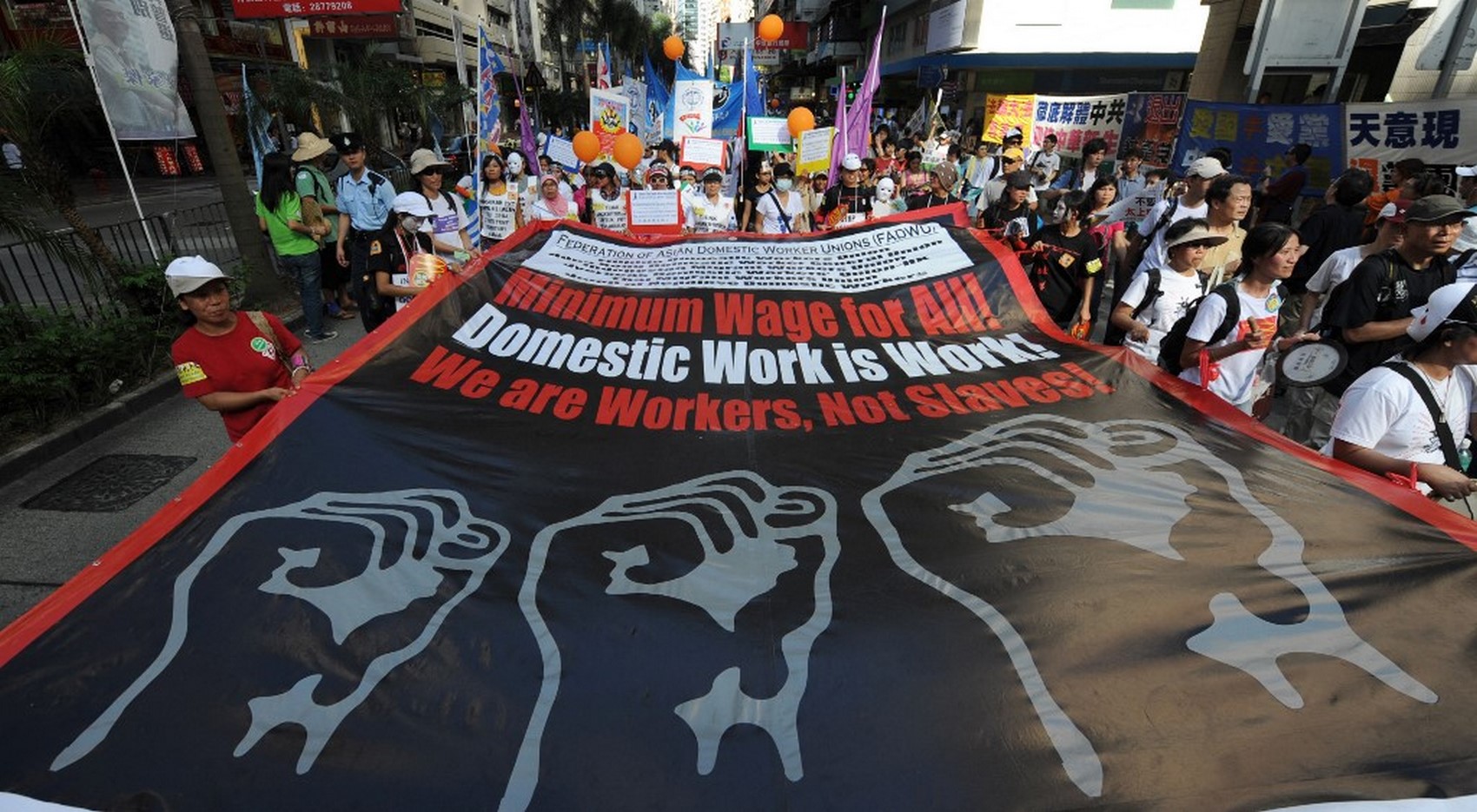

The turnout shrank once more in 2010, when some 52,000 Hongkongers expressed hopes in “going forward.” Organisers led people to put the city’s future “in [their] hands.” Many migrant workers also took to the street under the sweltering heat to ask for a minimum wage, saying they were not “slaves.”

Realising universal suffrage remained as one of the many demands.

2011: ‘Give me back dual universal suffrage in 2012; down with developer hegemony; Donald Tsang step down’

The CHRF reported a sharp jump in the July 1 turnout in 2011, when they said 218,000 people filled the streets, marking the highest number of participants during then-chief executive Donald Tsang’s term. Demanding his resignation was one of the many demands of the year.

HKUPOP and the government’s estimated turnout was much lower, as they reported 58,000 and 54,000, respectively.

2012: ‘Kick away collusion between party officials and businessmen, defend freedom & fight for democracy’

As Leung Chun-ying was sworn in as Hong Kong’s new chief executive in 2012, some 400,000 people cast doubt on their new leader, according to CHRF’s estimates.

Many held papers with Leung’s face printed on it, with a line reading: “Say no to Hong Kong Communist regime.” They accused Leung of being a “liar,” and demanded that he step down, on the first day he assumed power.

2013: ‘Independence of the people; immediate universal suffrage’

A year after Leung Chun-ying took office, the number of July 1 marchers continued to rise and reached 430,000 in 2013, the CHRF said. It was the highest turnout since 2003. Demonstrators again asked Leung to step down, while some waved British colonial flags. The organisers also said the civil disobedience movement Occupy Central was “ready to go.”

2014: ‘Fight for universal suffrage; Leung Chun-ying step down’

In 2014, Hong Kong saw around 510,000 people join the July 1 march – the highest turnout in recent years. It came more than a year after scholars including then-HKU law professor Benny Tai promoted the “Occupy Central” campaign as a “non-violent” civil disobedience campaign to push for universal suffrage by 2017.

Occupying the business district of Hong Kong was only part of Tai’s proposal and was said to be the “last resort.”

Over 500 people were arrested after the march ended, when they staged a silent sit-in in Central as a rehearsal for the occupy movement proposal.

More than two months later, the 79-day pro-democracy Umbrella Movement street occupations began after Beijing decided that leadership candidates would be nominated by a “broadly representative” committee, rather than being openly nominated.

During the movement, thousands of protesters occupied roads around the legislature and two other main districts following a student sit-in. Many leading figures including legal scholar Tai and then-student leader Joshua Wong were jailed in the years following the police clearance.

2015: ‘Build a democratic Hong Kong, retake our city’s future’

In the aftermath of the Umbrella Movement, which resulted in more than 1,000 arrests, the July 1 march turnout plunged to only 48,000 in 2015, organisers estimated. The figure was the lowest since 2008, as Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement was at a low ebb, beset with in-fighting and fatigue.

HKUPOP recorded a turnout of 28,000, while the government said only 20,000 took part in the march.

2016: ‘Battle against 689; Stay united, safeguard Hong Kong’

While the CHRF said the turnout of the July 1 march rose back to 110,000 in 2016, HKUPOP and the authorities reported the showing to be between 20,000 and 30,000.

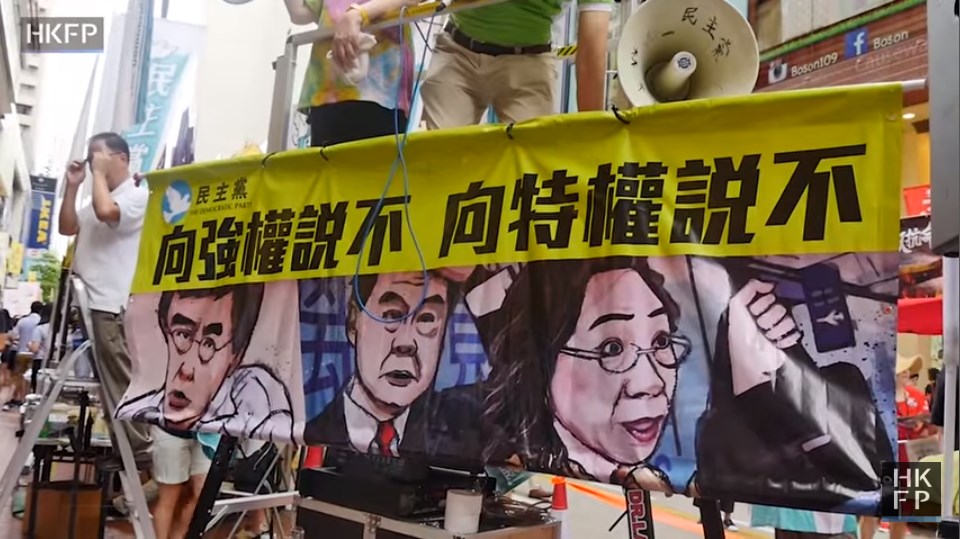

Demonstrators once again voiced discontent against then-leader Leung Chun-ying, referring to him as “689,” the number of votes he gained to be selected by the Election Committee for the top job.

2017: ‘One Country, Two Systems, a lie for 20 years; Democratic self-rule, retake Hong Kong’

In 2017, Hong Kong celebrated two decades since returning to Chinese rule. CHRF said around 60,000 people joined the march, with demonstrators calling on Beijing to release dissident Liu Xiaobo, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. He died weeks later on July 13, 2017.

Some accused the Central Government of making a “fake promise” to Hong Kong over the past two decades. Localist and pro-independence activists were among those who joined the annual day of dissent, including Tony Chung, who is now in prison over national security law secession charges. The then-secondary student appealed to Hongkongers that Hong Kong independence was “the only way out.”

Advocating for independence is now criminalised under the security legislation.

2018: ‘End one-party rule, refuse to let Hong Kong fall’

Hong Kong demonstrators expressed fear over dwindling freedoms and Chinese encroachment at the July 1 march in 2018, when organisers put the turnout at 50,000. But police put the figure at 9,800 – the lowest on record.

The line “End one -party rule” was printed on the CHRF’s banner, which was one of the five “operational goals” of the Hong Kong alliance before it disbanded in September 2021 under pressure from the authorities.

The government also alleged in October 2021 that the slogan amounted to “subverting state power.”

2019: ‘Withdraw extradition bill; Carrie Lam steps down’

In the midst of Hong Kong’s worst political turmoil in decades, organisers estimated that 550,000 Hongkongers took to the streets on July 1, 2019, around a month after the extradition bill protests erupted.

Demonstrators rallied for democracy and chanted slogans such as “free Hong Kong” and “democracy now.” The face of then-chief-executive Carrie Lam was printed on red placards, with some demonstrators labelling her as “the traitor of Hong Kong” amid calls for her to “step down.”

Despite Lam’s pledge in mid-June to suspend the controversial extradition bill, marchers called for the proposed law – which would allow the transfer of suspects to mainland China – to be completely pulled.

They also urged the government to set up an independent inquiry to look into alleged police misconduct during protest clearances, release whom they saw as political prisoners, restart democratic reform and retract the characterisation of an earlier protest as a “riot.”

While the march remained typically peaceful, hundreds later surrounded the Legislative Council Complex and tried to break into the building using trollies and metal bars. They stormed the legislature after the July 1 march, vandalised the interior and spray-painted anti-government graffiti on the walls. They also defaced the HKSAR emblem inside the chamber, tore down portraits of heads of legislature and tore up a copy of the Basic Law.

2020: ‘We really fucking love Hong Kong’

A day after the Beijing-imposed national security law came into force, thousands of Hongkongers defied a police ban and gathered on the streets in Causeway Bay and Wan Chai regardless.

Marchers followed the usual July 1 procession route, with some holding a long, narrow black banner with the line “We really fucking love Hong Kong” printed on it. Among the sea of people were hand gestures that signalled “Five demands, not one less,” while some held placards reading “Persist with the five demands. Resist the evil national security law.”

Despite the new law that criminalised secession, subversion, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts, some demonstrators waved pro-independence flags and chanted slogans such as “One nation, one Hong Kong.” Some protesters dug up bricks and scattered them on roads, while some set fire to storefronts.

Many gathered outside Times Square in Causeway Bay where people shouted the ubiquitous protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times.” The government declared a day later that the phrase had secessionist, subversive and pro-independence connotations.

A man with a Hong Kong independence flag became the first to be arrested under the national security law. Police made more than 370 arrests on that day as they cleared protesters by firing tear gas and pepper balls, as well as deploying water cannon trucks.

The Force also debuted a new purple warning flag, telling the crowds that their display of banner or flags, chanting of slogans or other behaviour had an intent to breach the sweeping security legislation.

2021: No rally as police seal off Victoria Park

As the Chinese Communist Party marked its centenary year, Hong Kong police banned the July 1 march for the second consecutive year in 2021 citing restrictions on public gatherings during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Force sealed off six football pitches, basketball courts, the central lawn, and entrances of Victoria Park, the starting point of previous July 1 marches.

It was the first time Hong Kong saw no large-scale rally or march on the traditional day of protest. The League of Social Democrats (LSD) was one of the few pro-democracy groups that managed to set up a street booth in Causeway Bay. The group put up a banner asking the authorities to free its members who were either jailed or in custody, including Jimmy Sham, “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, Figo Chan and Avery Ng.

The LSD also handed out leaflets detailing the history of the July 1 march.

The Force thwarted attempts to distribute placards that read “resolutely defend this city” by the now-defunct Student Politicism in Mong Kok. Its convenor Wong Yat-chin was among at least 11 arrested on that day under the colonial-era sedition law.

2022: A protest-free July 1, as activists’ homes searched by police

As one of the last pro-democracy groups still active in Hong Kong, the LSD announced they would not hold any protest activity on July 1, 2022, after some of their volunteers were called in to meet officers from the police National Security Department.

The city was on high security alert as Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited the city for the first time since 2017. Police sealed off the areas where Xi stayed, visited and passed by as “core security zones,” where only accredited individuals and vehicles could enter.

The LSD chairwoman Chan Po-ying, wife of Leung Kwok-hung, said on Thursday that national security police conducted searches at her home and the residences of five other members: Raphael Wong, Avery Ng, Tsang Kin-shing, Dickson Chau and Yu Wai-pan.

They were also taken to different police stations for a meeting, she said, during which they were warned not to hold any protest activities as Hong Kong marked 25 years since its Handover from Britain to China. “The details of the meeting cannot be disclosed. Also, everyone is being followed and watched by the police,” Chan said in a statement.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team