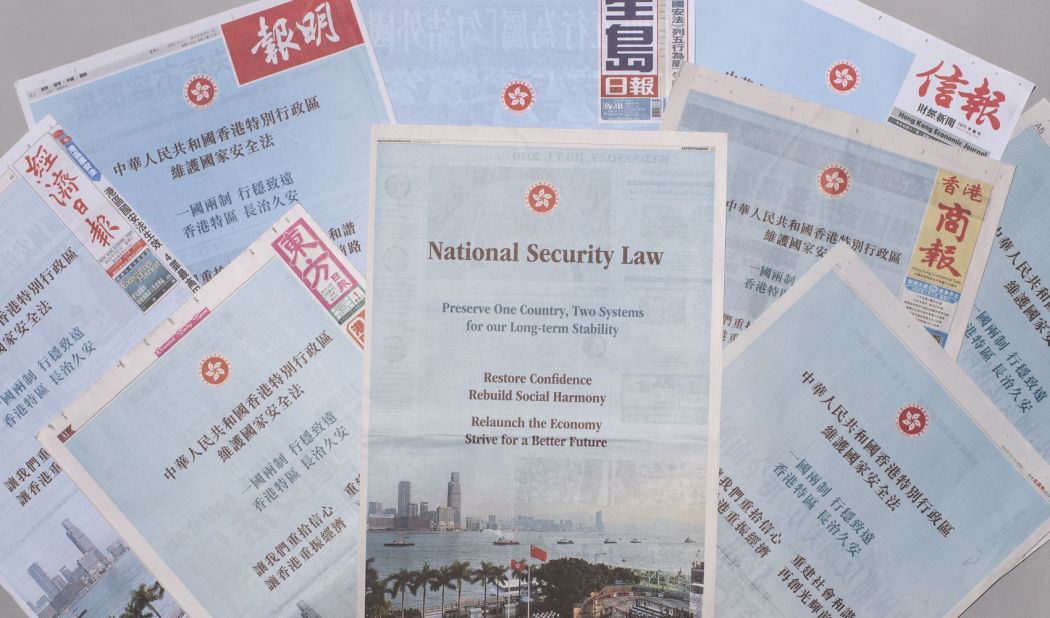

Since the passing of the National Security Law, the streets of Hong Kong have been eerily calm. Large-scale marches and guerrilla-style street protests are no longer a weekly sight. While some Western pundits and expats were quick to declare that Hong Kong and its pro-democracy movement is dead, Hongkongers’ spirit of resistance lives on. It has taken on a transnational orientation as they advocate for protesters across the world – most recently in Belarus and Thailand.

Since the 2019 protests began, Hongkongers have experienced over a year of heartbreak, trauma and violence inflicted by a government and police force that cannot be held accountable. As grassroots uprisings spread across the world since the pandemic, their intimate encounter with protests and resistance have given rise to a new wave of transnational solidarity.

As Hongkongers watch protest footage abroad that echoes our own, we feel a visceral connection and kinship with grassroots activists facing similar obstacles and violence.

Like the anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong last year, the grassroots movements that have been spreading across the world are mostly decentralised and youth-led, and make use of digital technologies and guerrilla street tactics to challenge authoritarian governments. Most importantly, like Hong Kong protesters who challenge Beijing’s governance, these movements seek to dismantle longstanding systems of power, and by doing so, uncover the state’s willingness to inflict violence on its people to squelch dissent and restore the status quo.

Common across all these movements are state regimes that monopolise power and are eager to invoke a state of emergency and implement draconian laws to criminalise protesters. Recently, mirroring in some respects the Carrie Lam administration, the Thai government declared a state of emergency and implemented a ban on gatherings in response to ongoing protests against the monarchy and military rule.

Around the same time as Beijing announced the National Security Law for Hong Kong, the Duterte regime in the Philippines implemented a sweeping anti-terrorism law with similar chilling effects. The basis for Hongkongers’ solidarity with movements abroad, hence, is our shared struggles against authoritarian state governments and militarised police forces that do not hesitate to inflict bodily and emotional harm on citizens should they become unruly.

Given these similarities, journalists and commentators have written extensively about how the Hong Kong protest inspired guerrilla “Be water” tactics around the world, especially during global uprisings in 2020. More recently, cautioning against a callous dismissal of the Hong Kong movement as a failure, Jeffrey Wasserstrom writes, “the city’s latest struggles added significantly to the global repertoire of resistance.”

The cross-movement influence between Hong Kong and elsewhere is a two-way street. While the 2019 Hong Kong protests have influenced organisational and protest tactics in anti-authoritarian movements abroad, the current wave of grassroots uprisings, in turn, prompts Hongkongers to develop a transnational understanding of grassroots activism and solidarity.

While Hongkongers have previously focused mainly on lobbying powerful Western governments for support, they have since expanded their transnational advocacy to grassroots movements that challenge state regimes. This is an important shift as it highlights how our struggles are interlinked across movements, despite geographical distance and historical differences.

While the National Security Law has dampened street protests in Hong Kong, it has not stopped Hongkongers from expressing their spirit of resistance, which now takes the form of online transnational advocacy. During the Hong Kong protests, people made very effective use of digital technologies to circumvent surveillance, circulate information and advocate for the five demands.

As protests in Belarus and now Thailand intensify, Hongkongers once again make use of social media platforms to demonstrate transnational solidarity. In addition to retweeting posts from Belarusian and Thai protesters and journalists, Hong Kong Twitter users have also shared protest tactics and translated information about those protests into Chinese so they could reach a broader audience.

In late September, a Hong Kong illustrator started an art campaign on Twitter that motivates Hongkongers to co-create a painted human chain to connect the two locales and movements. Under #HK2Belarus, there are original artwork and photo collages that demonstrate Hongkongers’ support for Belarusians as they challenge the Lukashenko regime.

As #MilkTeaAlliance morphed from a sarcastic Internet meme to a symbol of transnational anti-authoritarian struggles, Hong Kong netizens shared footage and messages from Thai protesters on Twitter to amplify their voices. Using the hashtags #StandWithThailand and #WhatIsHappeninginThailand, the Instagram platform @hkpostmanchannel collected over 300 messages of support written by Hongkongers to Thai protesters. While these demonstrations of support are most visible on social media platforms where Hongkongers can protect their identity and privacy, they are not limited to digital spaces.

Prominent pro-democracy activists and lawmakers such as Joshua Wong, Ted Hui and Figo Chan held up a bilingual banner outside the Thai Consulate in Hong Kong to condemn violence against Thai protesters. Overnight, graffiti materialised on a traffic bridge in Tai Koo: “#StandWithThailand #Save12HKYouths.” Even more courageously, a representative from grassroots advocacy group Student Politicism made a public speech in Mong Kok, urging Hongkongers to support grassroots activists in Xinjiang, Belarus, and Thailand.

“I hope we Hongkongers can expand our vision and support beyond our local struggle. When we were protesting, Thai people supported us not because they were obligated to. I hope that now when they are facing authoritarian suppression, we will support them too.”

Echoing this sentiment of mutual support, political commentator Kevin Yam reminds Hongkongers that while it is tempting to continuously highlight similarities between the Hong Kong and Thai protests, we need to keep the focus on the struggles and courage of the Thai people.

This transnational solidarity differs from previous international outreach efforts: rather than centring local struggles in Hong Kong to a Western audience abroad, recent expressions of transnational solidarity emphasise mutual support and solidarity with other protesters as co-strugglers against authoritarianism. This orientation decenters traditional power structures by connecting directly with other grassroots activists, instead of state governments that are complicit in oppression.

Protesters in Thailand and Belarus have responded in kind: they chanted slogans and unfurled flags for the Hong Kong movement that were no longer permitted in Hong Kong under the National Security Law. As activists around the world challenge state governments and seek to dismantle unjust political structures, Hongkongers’ new transnational orientation ensures that we will have a seat at the table as activists worldwide imagine and create new political futures.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.