In the words of the Global Times, Jimmy Lai has made Hong Kong the “frontline” between the US and China. While I think they give too much credit to Lai, there is no doubt that the US and China have managed to get themselves into the legal equivalent of an arms race.

Neither wants war, but both desire domination. In pursuit of this, both have passed laws that compel actions: in China’s case, the national security law throws an ever-widening net for suspects and crimes; in the case of the US, an ever-widening net of targets for sanctions.

On the current trajectory, Hong Kong will lose its largest trade partner, and the United States could lose trillions of dollars worth of companies listed on its stock markets, and an essential part of its supply chain. And, of course, each side blames the other. It is difficult to know how to de-escalate this–especially when a mere suggestion may be seditious. But the stakes are too high not to give it a try.

There is an old but widely accepted idea that the legitimacy of a government is drawn from the consent of its people. This idea goes back in Chinese history to the pre-Confucian idea of a `mandate of heaven’ (天命), and in Western history, to the period surrounding Great Britain’s civil wars two millennia later (the Brits were a little slow on the uptake). The substance is pretty much the same: a government that has the consent of its people acts legitimately, and one that has lost it, does not.

The trouble with consent is that most of us have never been asked. We have no choice over the country of our birth and are never asked “Do you consent to this government?” So, the idea that a consenting act ever takes place is laughable. However, there are other ways of showing consent: by peacefully obeying laws, working with law enforcement rather than against it, and by constructive input – such as this – when policy is being formulated.

Despite the ideological abyss between the People’s Republic of China and the US, both governments have the consent of their peoples. The PRC government has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty in a single generation, has clamped down on the corruption that characterised the early part of the Reform era, and is getting better and better at things such as honest policing and criminal justice. I am not glossing over the problems it faces, but I am saying that China’s done a great job and, as a result, the citizens by and large consent to communist rule.

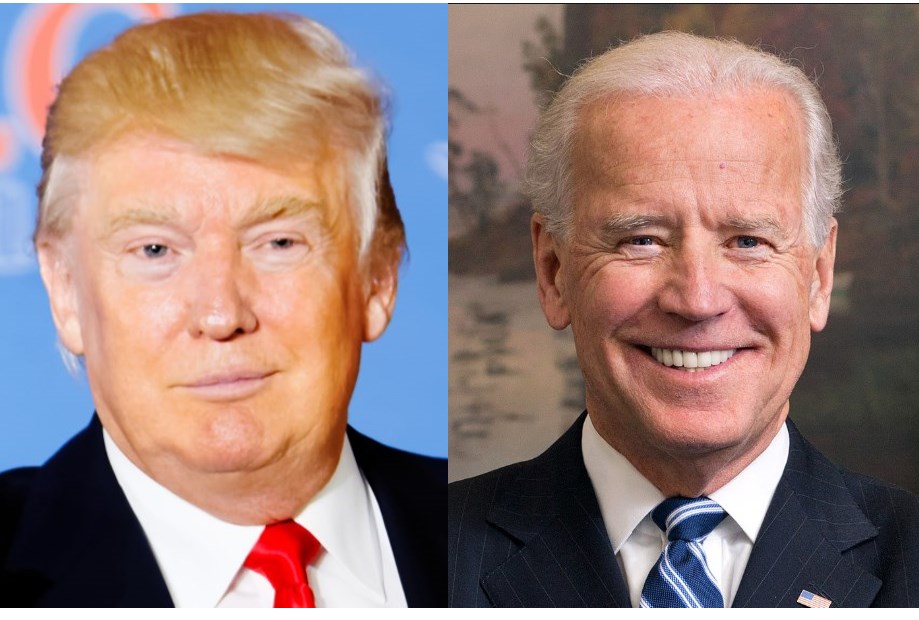

That the US has issues is beyond dispute: the Black Lives Matter movement exposes systemic injustice and racism, the police appear to be an alternative form of criminality* and, although the importance of the presidency is overstated, Biden vs. Trump is a dismal choice (though Harris vs. Pence is promising). Yet, by and large, the US system functions and has the consent of its people.

Consent goes two ways, though. Governments, for their part, earn consent by enacting just laws, by providing decent public services, and by listening. And, when it comes to listening, the Chinese and American systems are not as far apart as they appear: both are representative of their people.

Let’s not confuse representative government with democracy. Democracy is one mechanism among many to represent the people to government. It is the American one, albeit undermined by vulnerability to demagogues, blatant gerrymandering and entrenched angry-old-white-man power. But for all its manifest imperfections, the needs, wants and aspirations of the US people are represented to the US government, which acts on this information–however imperfectly–when enacting just laws and providing services.

China instead has the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), which operates at the national, provincial, prefectural and county levels, and which draws its members from all walks of society (the author of the Wuhan Diary, Fang Fang, served in it, for example, but was never a member of the communist party). These conferences represent the needs, wants and aspirations of the people to the government which, however imperfectly, acts.

So, despite the surface differences, China and America have representative systems of government which engender the consent of their peoples. And then we have Hong Kong.

The Global Times accuses Lai of “fundamentally turning Hong Kong, China’s window to the outside world, into the US anti-China frontline.” Far be it from me to accuse the PRC government of hyperbole, but if Lai were able to do so, it was because the Hong Kong government’s own performance created such fertile ground for dissatisfaction.

In Hong Kong, any alignment of the needs, wants or aspirations of the people with government policy is purely coincidental. Rather, policy is formulated by a bunch of Western-educated Christians second-guessing what atheist sons (and the occasional daughter) of the Cultural Revolution may or may not want. If that doesn’t produce an answer, they fall back on industry lobbyists which they themselves all but appoint to the Legislative Council.

As a result, government policy is wildly out of alignment with the reality of day-to-day life. At the bottom end of the socio-economic scale, for example, the going price for a coffin bed is HK$2,000 per month while the government handout is $1,800. This results in an ever-growing number of homeless people. As more and more of the economy gets taken over by cartel-monopolies, the lower- and middle-classes have seen a steady erosion of social mobility; real incomes have stagnated.

Meanwhile, as the government builds one white elephant after another, it proposes with a straight face–and when a whole bunch of container ports remain under-used and government land sits vacant–to build an artificial island in 15-plus years to solve a housing crisis that has already been with us for 15-plus years.

As a result, Hong Kong has a government that is not representative, so has lost the consent of its people, and hence its legitimacy.

I hope The Global Times is wrong, and that Hong Kong will not become “a US anti-China frontline”. But I think they are right when they point to “pushing Hong Kong society toward the US in terms of values”: there are many who felt more represented under colonial rule than now.

If that is to be reversed, the system of government needs to change, and change fast. That can only start at the top. The Joint Declaration is a dead duck, and the Basic Law carries provisions for its own amendment: if genuine democratic representation is not on the cards, then drop the charade and include Hong Kong in the CPPCC system. Demonstrate by actions that that system better represents the people’s wants, needs and aspirations.

The pan-dem political opposition is, for all practical purposes, dead. Move on. There is constructive work to be done. Focus on that, win back the consent of the people by ensuring their wants, needs and aspirations are represented in formulating government policy. This will make the national security law unnecessary: still on the books but never used because of a consenting citizenry.

That, in turn, will prevent Hong Kong from becoming the frontline. Without that frontline, the risk of confrontation becomes ever smaller. As a Chinese senior diplomat recently said, neither side wants the situation to deteriorate further–but arms races have a habit of going that way.

*Anthony Burgess uses this phrase in his autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.