On October 25, Hong Kong police obtained a court order to prevent the disclosure of personal data belonging to officers and their extended families – a practice also known as “doxxing” – but lawyers have warned that the move could have wide-reaching implications.

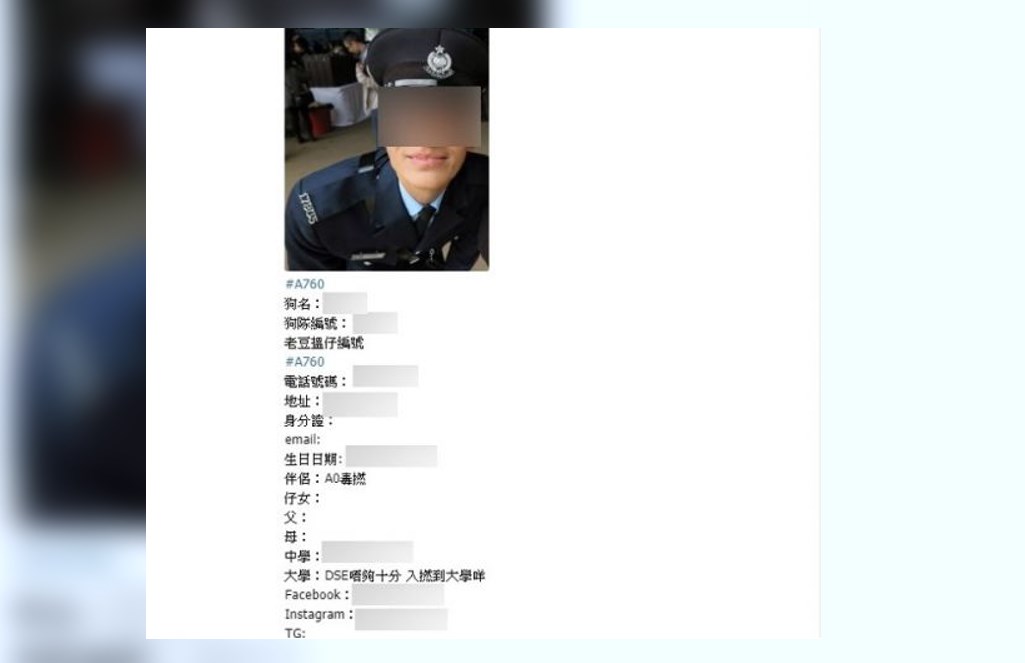

Police said that officers have been affected by “nuisance and intimidation” since the citywide protest movement began in June. Some have received harassing calls, threatening letters, or had their identities misused to apply for loans or make online purchases, the force said.

The rise of doxxing was what prompted the move to seek help from Hong Kong courts: “These acts constitute serious intimidation and harassment to the police officers and their family members, causing grievous concern over their personal safety and mental distress,” the police said in a statement.

However, lawyers have raised concerns over the fine print of the injunction, which also prohibits “intimidating, molesting, harassing, threatening, pestering or interfering” with officers and their extended family.

“It is both broadly and vaguely written… some words are ill-defined and leave grey areas,” barrister Johnny So told HKFP.

The interim injunction will remain in effect until a hearing on November 8, where the Department of Justice and police chief will argue their case for a formal injunction.

Police made the first batch of arrests over doxxing in July, but the trend has shown no signs of slowing down. Messages containing details related to prominent officers have appeared on “Lennon Wall” message boards across the city, prompting officers to clear them.

One Telegram channel for sharing officers’ personal data has around 200,000 subscribers, with an administrator saying they will continue despite the injunction.

The injunction issued last month restrains anyone from sharing the “name, job title, residential address, office address, school address, email address, date of birth, telephone number, Hong Kong Identity Card number or identification number of any other official identity documents, Facebook account ID, Instagram account ID, car plate number, and any photograph” of any police officer, their spouse, or their respective family members.

Legal scholar Eric Cheung said that the restriction was “overly wide,” noting that the wording of the injunction would cover everyday situations such as using the government phonebook or calling the roll at schools.

Barrister So added that the injunction could affect people recording videos of police officers at work, especially if the videos feature misconduct. “What this shows is that the government is using every tool at its disposal,” he said.

Beyond doxxing

While the police commissioner and the Secretary for Justice initially focused on doxxing in their court application, the injunction text also restricts behaviours that have nothing to do with personal data.

Separate from the prohibition against doxxing, the court order restrains anyone from “intimidating, molesting, harassing, threatening, pestering or interfering” with police officers, their spouses or their respective families.

So said that the provision left a lot of grey areas: “What if someone is engaged in a heated debate with a frontline police officer, and utters a swearword? The officer can say that it constitutes harassment.”

Hong Kong does not criminalise the act of insulting a police officer, though pro-establishment figures have called for such legislation in recent years. In 2017, pro-Beijing lawmakers Junius Ho, Priscilla Leung and Horace Cheung proposed the idea with a maximum penalty of HK$5,000 and one year in prison, but the amendment did not pass.

So said that, if police are allowed to take legal action against ill-defined “harassment” or “pestering,” it would be as if Hong Kong enacted a law against insulting police – but without oversight from the Legislative Council.

Last Monday, HKFP asked Senior Superintendent Steve Li to clearly define what constituted “intimidating, molesting, harassing, threatening, pestering or interfering” under the injunction.

Li said that he would not go into detail: “I would like to focus on the most important part of this injunction, which is ‘unlawfully and wilfully.’ That [shows how] carefully we treat this injunction order.”

The injunction names its defendants as “persons unlawfully and wilfully conducting themselves in any of the acts prohibited under paragraph 1(a), (b) or (c) of the Indorsement of Claim,” with the three sub-paragraphs listing the banned acts. Neither the court document nor government press releases define “unlawfully and wilfully.”

Asked if a pedestrian shouting insults at the police would contravene the injunction, Li said that the behaviour would be permitted as long as it was not “unlawful.”

“It is very easy, no difficulty at all. There is no hidden [catch] for this one,” he added.

However, So said that he had reservations about Li’s response as it was “too vague.” It might take a judge’s ruling for the public to truly understand the ambit of the injunction, he added.

Press freedom fears

The police injunction also sparked concerns that it would affect the media, though Superintendent Swalikh Mohammed assured reporters outside the courtroom last month that the press were not the intended target.

The injunction lists no exemptions or defence for anyone. Chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association Chris Yeung urged the government to clarify whether the media were exempt, adding that it was “basic stuff” for news reports to include an officer’s name and rank. News cameras also cannot avoid filming officers’ faces, he added.

Since the interim injunction was ex parte – involving only the party who made the application – no representatives from the media or civil society groups provided input to the court before the application was granted.

Pro-democracy lawmaker Charles Mok, who represents the information technology sector, said that the move should be viewed in the larger context of police curtailing government transparency.

“It is like the gradual tightening of information which has been publicly available in the past,” Mok said, adding that the injunction was “unreasonable and unfair” because it prioritised the police above other people who were doxxed.

The injunction was the latest in a series of legal developments that hide police officers from the public eye: in the same week, the Junior Police Officers’ Association won a separate interim injunction to bar the public from checking personal details on the voters’ registry.

In recent months, the Department of Justice has repeatedly asked courts to grant anonymity to police officers appearing in court, on the basis of protecting them from doxxing attempts.

As Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement approaches its fifth month, protesters have insisted on their demand for government accountability – and in particular, personal accountability for police officers who abused their power and broke the law.

One protest group, Keyboard Frontline, issued a statement condemning the injunction against doxxing as “censorship,” and called on the court to rescind it on November 8.

“The plaintiff’s only conceivable interest in bringing the lawsuit is government secrecy. Official propaganda surrounding the lawsuit conflated preservation of government secrecy and anti-doxxing,” the group said.

“In a free society, a police officer has no right to anonymity or to be forgotten.”

Hong Kong Free Press relies on direct reader support. Help safeguard independent journalism and press freedom as we invest more in freelancers, overtime, safety gear & insurance during this summer’s protests. 10 ways to support us.