To Japan last week for a Scottish dancing event (I realise that sounds a bit odd: another time) and a bit of tourism, which took me to the grave of Tokugawa Ieyasu, revered as the bringer of unity to Japan after a period of civil turbulence, and the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which ruled the country for 250 years.

Actually there is some doubt about what is in this particular grave. Ieyasu was first buried somewhere else. According to legend his remains were moved to Nikko, where I may or may not have visited them, a year later. As this is supposed to have happened in 1617 it is difficult to check.

Suggestions that one or both of the graves should be opened for a peek at the contents have been rejected, so the doubts persist.

Never mind. Downhill from the grave and the cluster of very beautiful temples built round it by pious, or propagandistically-inclined, descendants, there is a museum. The museum shows movies, and one of them is a rather charming animation in the Japanese style on Ieyasu’s life.

This is probably intended for children. But it is the only offering with English subtitles.

Of course such depictions involve some, shall we say airbrushing? You could level a similar objection to James Clavell’s “Shogun”, in which Ieyasu appears in a rather sympathetic form, thinly disguised under the name of Toranaga.

In reality, he lived in violent and treacherous times, and was not most people’s idea of a dream son-in-law. According to his Wikipedia page he was “not very well liked or personally popular, but he was feared and he was respected for his leadership and his cunning.”

He claimed to have fought in 90 battles, which was perhaps an acceptable total for a long life in that era. As well as these stag slugfests the victims of his homicidal side included an alarming number of women and children, including his first wife and the 8-year-old heir of a rival. Well, times have changed.

Part of the museum’s biographical movie has the young Ieyasu asked by a picturesquely aged instructor (think Pai Mei in Kill Bill) which of three attributes a state could do without: abundant food, an army, or honour.

His answer to this question, “an army”, is correct. The second question is which of the three should be discarded next. His answer “honour”, because men cannot live without food, is wrong.

The aged instructor says that men with food but no honour are no better than pigs.

One may well doubt whether this story, even if it came from Ieyasu himself in later life, has been embroidered. Only the sexist language is clearly 17th century.

But never mind the history. What left me gobsmacked was the notion that children now visiting museums should be encouraged with a straight face to take the view that honour is more important than wealth and power.

To Western eyes that seems a pleasing but antiquated idea.

I realise that there was no Golden Age in which European people were motivated only by matters of honour, or morality, or ethics. People respond to a variety of motives and, with few exceptions, greed is generally one of them.

But those of my compatriots who participated in the Second World War generally regarded this as a useful and meaningful experience, despite the sufferings and the loss of friends involved, not because it enriched the country – which it didn’t – or preserved the Empire – another disappointment – but because it was the right thing to do in the circumstances.

“The right thing to do”? How old-fashioned that sounds.

Our century suffers from what is known in Germany as the “Adam Smith problem”. This is shorthand for reading Smith’s famous “Wealth of Nations”, which celebrates the emergence of collective economic success from individual self-interest, without also reading the “Theory of Moral Sentiments” which explores the reasons why people do not in practice always behave selfishly.

We have of course come a long way in explaining moral behaviour since Adam Smith, who believed that the mechanism he described had been created by God to keep men on the strait and narrow path.

But his basic conclusion was right: people are honourable because they wish to be thought well of by their surrounding community, and hence, having internalised that community’s values, by themselves.

This rather simple idea explains many of our apparently intractable modern problems. Globalisation, for example, appears to be immoral precisely because it merges into one competing network many different ethical communities.

This produces a race to the bottom. People who are loyal to their workers are outcompeted by unscrupulous exporters of jobs. Mobile phones made in prosperous welfare-providing Finland, where workers have rights, cannot compete with those assembled by child slaves in China.

Toxic financial innovations, like leveraged management buy-outs or junk mortgage collections, are eagerly exported from places where they are barely acceptable to places where they were once not acceptable at all.

This is fostered by loyalty to economics. The Economist’s country reviews are carefully researched and exquisitely well written. But they rarely fail to come to the conclusion that the country concerned needs to free its labour markets and open its borders more to international trade.

Then there is the matter of Hong Kong budgets. These are based on the notion, assiduously propagated by the Chicago school of economics as the unlikely intellectual apologists for Ayn Rand, that the poor are poor because they are lazy, stupid or both.

This goes down well with the millionaires whose company and approval our senior civil servants find so congenial, because it implies that the rich are rich because they are industrious and intelligent.

So we get budgets which allocate more money to the rich – as “investment in the future” – in a variety of guises, and less to poverty alleviation: “sweeteners” which merely encourage the poor in their idleness and depravity.

We can also consider the tricky matter of relations between Hongkongers and China. This is not an economic problem. Hong Kong went from poverty to prosperity during the 40 years in which it got little help from the UK and none at all from China, which was busy exploring variations on lunacy with a Marxist flavour.

This has left us with a moral community incompatible with Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, which requires a quasi-religious belief in whatever the Party line currently may be.

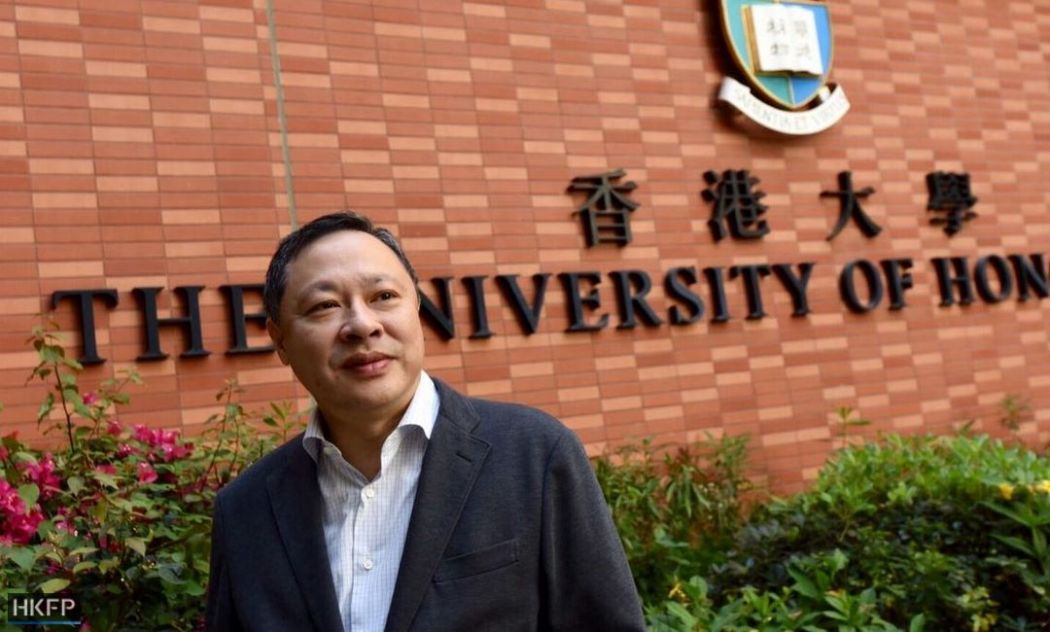

This becomes starkly apparent in the current row over what Benny Tai may or may not have said at a conference in Taiwan. Prof Tai’s attackers say that he said “Hong Kong might consider independence.” Prof Tai’s defenders point out that this consideration was conditional on the achievement of a “democratic China”.

A democratic China is one of those interesting combinations of words, like “a tropical snowstorm” or “Hong Kong’s gold medallist in Olympic cross-country skiing”. We know roughly what it would look like but we expect to see it right after some South Korean genetic manipulator announces the creation of the first flying pig.

In other words, Prof Tai’s statement was about as hypothetical as a statement can be. In fact in a democratic China outright independence would not be particularly attractive. If you said, on the other hand, that if being part of China meant submission to a brutal despotism with no respect for the rule of law, Hong Kong might be attracted to independence, then that would be subversive.

But these distinctions are lost on local lefties, who are required to believe that Communism in China is not only admirable, but immortal.