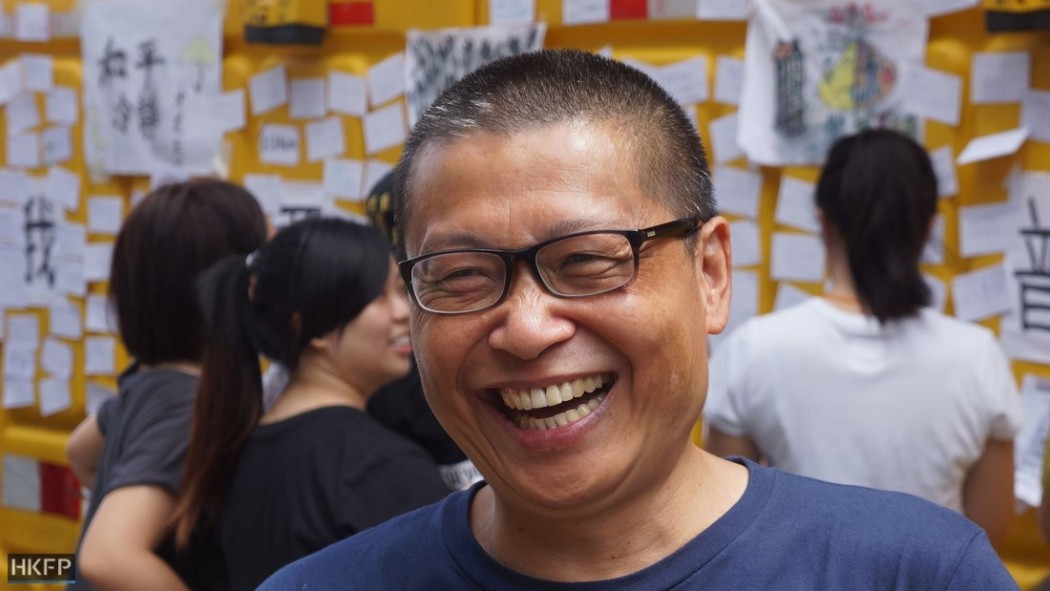

When sociology professor Chan Kin-man agreed to help law scholar Benny Tai lead an unprecedented civil disobedience campaign, he was prepared to see his career ruined.

In 2013, the two scholars, together with the Reverend Chu Yiu-ming, launched the Occupy Central with Love and Peace campaign to advocate genuine universal suffrage, as the government was preparing a reform package for the chief executive elections.

The package, setting a high bar for non-establishment figures to run in elections, would eventually give rise to the 2014 pro-democracy protests that shut down the heart of Hong Kong.

Occupy Central’s first crisis

While Chan and Tai worked closely on public communication, the Reverend Chu, who has decades of activism experience, was mainly responsible for coordinating with political and civil society groups.

But the three founders did not always agree. “I knew from the beginning that it would take time to reconcile our differences,” said Chan.

According to Chan, a main difference was Tai’s academic mindset on the one hand, and Chu’s pragmatism on the other.

Chan recalled that their first “deliberation day” event marked the campaign’s first crisis. “Occupy Central was very close to falling apart on that day,” said Chan. “Chu even said he would quit afterwards.”

The purpose of deliberation days was to bring together individuals to discuss their views on Hong Kong’s election systems and, hopefully, find a compromise. However, while Chu wanted to strengthen the pro-democracy camp and find practical solutions through the event, Tai saw it as a research opportunity.

Chan said that after Chu had invited hundreds of politicians and activists, Tai asked HKU’s Public Opinion Programme to bring a random sample of citizens as he wanted to compare the opinions of pro-democracy supporters and the general public.

As a result, political groups told Chu that they might pull out because they thought Occupy Central was not about promoting democracy, but rather to conduct research.

Meanwhile, Chan worried that pro-establishment media like TVB would interview those members of the public and frame the story so that a good number of participants did not appear to find genuine universal suffrage an important goal.

Eventually, Chan sought a middle ground between Tai and Chu by placing HKU’s participants at a separate venue, so that the press could not interview them.

As it turned out, according to Chan, political groups also realised the value of letting everyone speak on an equal footing, as pro-democracy leaders typically make decisions without much public participation.

Reconciling differences

Over time, the three founders worked through their differences, though disagreements continued to exist “until the very end,” said Chan.

For example, though Tai was usually the spokesperson for the campaign, behind the scenes Chan put a lot of effort into brainstorming campaign messages. However, Chan said Tai did not always follow the lines of their pre-crafted messages.

“As a scholar, Benny thinks that the best way of dealing with the media is to be sincere, frank and honest, and there is no need to polish your answers,” said Chan.

“But Reverend Chu and I disagree: you need to carefully craft your messages to the public.”

Activist since the 1980s

Chan’s take on effective campaigning came from his own activism experience. Although Tai may be better known internationally as the face of the 2014 Occupy protests, Chan has long been a notable figure in activist and NGO circles – in Hong Kong as well as mainland China.

In 1989, Chan protested outside the Chinese embassy in Washington DC against Beijing’s crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square. He was a university student.

As a fresh graduate, Chan had worked as a social worker and election campaigner in the 1980s before going to Yale University to study Hong Kong’s democratic development. There, he met Yale Professor Juan J. Linz, whose book Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation inspires him to this day.

When colonial Hong Kong saw a wave of emigration in the 1990s, Chan decided to return to the city because he felt that he “had something to contribute.”

Since then, Chan had been devoted to promoting Hong Kong’s democracy and China’s civil society development – from training NGOs to working with local officials – until 2014 when Beijing characterised Occupy as separatist and put pressure on groups that Chan had worked with.

On having to halt more than two decades of research on China’s civil society, Chan said that it was like removing a part of himself – despite having foreseen this outcome when he decided to come under the spotlight three years ago.

Radicalisation of Hong Kong politics

Towards the end of the Occupy protests, Chan said he had predicted the fragmentation of the pro-democracy camp as localist groups turned against the pan-democratic establishment and eventually advocated independence, an idea that the older generations of politicians consider to be a taboo.

He said that the recent LegCo election results, with around 20 per cent of the elected pro-democracy lawmakers belonging to the so-called “localist” or “self-determination” camp (such as Cheng Chung-tai of Civic Passion and Nathan Law of Demosistō), show that the older generations of pan-democrats are losing support to younger, more radical figures.

On the other spectrum of radicalisation is the middle class becoming cynical and self-protective, Chan said. “Those capable of emigrating are now talking about leaving Hong Kong.”

But Chan saw a ray of hope in recent politics: from the rise of professional groups that speak publicly against the government such as the Progressive Lawyers Group, to the latest LegCo and district council elections that saw new faces getting elected into the government.

He added that the fragmentation of the pro-democracy camp has been less intense than he had predicted, with the “less strong-headed” figures from radical groups Civic Passion and Youngspiration joining the legislature rather than the more outspoken ones such as Raymond “Mad Dog” Wong Yuk-man and Chin Wan, who authored a book on Hong Kong as a city-state.

ThunderGo: ‘Well-intentioned, but problematic’

Chan was also critical of Tai’s strategic voting plan ThunderGo, which has been criticised for causing pan-democrats to lose seats in the Legislative Council election earlier this month.

He said that from a scholarly perspective, Tai’s plan lacked a scientific basis to justify the choices of candidates to be “saved” through strategic voting.

Another fatal mistake of the plan, Chan said, was that the implementation details were never made clear to the public. It ended up with too many voters going to the polling stations during the last hours, whose votes were enough to “almost cause pan-democrats such as Civic Party’s Tanya Chan to lose their seats.”

“Benny’s plan was well-intentioned as always, but there were too many unresolved technical issues,” said Chan.

A new chapter of life

Today, the 57-year-old professor returns to a quiet life and focuses on writing. “I have been so busy over the last few years that I didn’t have time to go through my research notes and summarise them,” said Chan. “Now I finally have time for that.”

Chan also goes hiking with activist friends, a hobby he had avoided due to chronic knee pains. But since Occupy, he has been hiking regularly and even participated in an overnight charity hike last year.

He said although the process could be painful, “once you arrive at the finish line, you would feel like life opens up with unlimited possibilities.”

“If I, at my age, think this way, young people shouldn’t feel defeated,” said Chan. “What we see in Hong Kong is not the end yet – there are still many possibilities.”