Written by John Rennie Short.

A United Nations arbitration court will soon rule over the sovereignty of islands in the South China Sea, a territorial dispute between China and the Philippines with global implications.

In recent years, China has been asserting claims in the region and has built up atolls and islands to be large enough to stage military exercises. This region is of major economic and geopolitical significance, with its vital commercial shipping lanes, rich fisheries and massive natural gas and oil deposits.

Even before any ruling, China has rejected the U.N. process and argued that the Philippines should seek to settle the dispute through bilateral negotiations. The U.S., meanwhile, has been stepping up military exercises in the South China Sea in recent months.

These growing tensions focus attention on an emerging geopolitical hotspot, something I view through my perspective as a researcher of political geography and globalization. What is the background to these tensions and what are their likely implications and consequences?

Reassertion of global status

China’s economic success is obvious. In the past 25 years, it has grown to become the second-largest economy in the world, lifting millions out of poverty in rates of economic growth unparalleled in the modern world.

But it is crucial for non-Chinese to remember that China’s leaders see international political standing, not only economic clout, as an important issue. Heightened global stature not only makes up for a century when China was on the wrong end of asymmetrical relations with other powers, especially Japan, and subject to dismemberment and annexations, but it also reclaims China’s position as one of the world’s preeminent centers of power and influence.

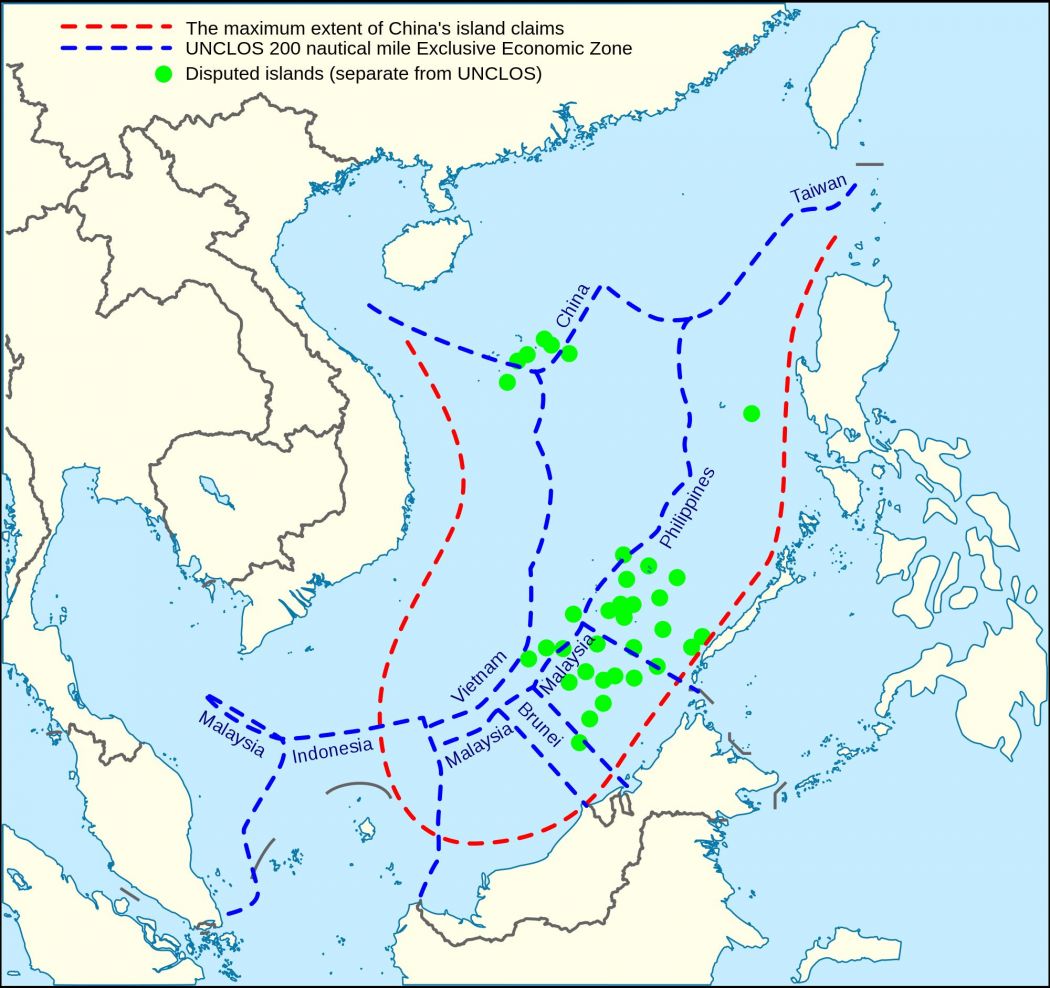

China claims a wide swath of territory in the South China Sea. It is often shown on Chinese maps as nine dashes and, indeed, referred to in those words.

Laws and zones

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), first introduced in the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of The Sea, are areas where states can claim exclusionary rights over marine resources. They have a limit of 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the coastal baseline, the seaward edge of its territorial sea.

Where EEZs overlap, as is the case in some parts of the South China Sea, it is up to the neighboring states in question to delineate the maritime border.

Matters are made more complex when small islands – rather than a coastline or continental edge – are used to define a nation’s EEZ and are claimed by more than one country. A country can establish territorial sea up to 12 nautical miles from a naturally formed island and from there can claim a 200-nautical-mile EEZ.

Part of China’s strategy in the waters of the South China Sea then is to lay claim over islands, natural and artificial, in order to establish sovereignty to claim the surrounding waters.

Many islands in dispute

China’s territorial claim overlaps with the EEZs of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei. There are a number of ongoing disputes over the islands in the South China Sea.

The Paracel Islands, for example, are claimed by both China and Vietnam. When China moved a giant oil rig to the region in 2013, it was seen as a direct threat by the Vietnamese and undermined China-Vietnam relations. The Chinese have built a surface-to-air missile defense system on Woody Island, one of the largest of the Paracel Islands, and recently added a helicopter base to Duncan Island.

The Scarborough Shoal, a 60-square-mile chain of rocks and reefs, is claimed by both China and the Philippines.

In 2012 China took effective control by reconstructing seven islands. Control over the islands in the shoal allows China to monitor U.S. military activity.

The Philippines responded by taking the issue to the U.N. in 2013, rather than pursuing bilateral discussion. The Philippines, unlike other states in the region, has fewer economic ties with China and close military ties with the U.S. The U.N. ruling will be the result of this one-sided arbitration case.

The election of a new president may, however, herald a new change in Filipino-Chinese relations. Benigno S. Aquino III has suggested the U.S. would need to respond militarily if China develops the shoal to maintain credibility in the region. And incoming President Rodrigo Duterte has said he’s open to direct negotiations with China.

And then there are the Spratly Islands, more than 740 reefs, islets, atolls and islands, to which six countries lay claim: China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines.

And all but Brunei have built or claimed outposts there. However, China’s activity has ramped up since 2013, when it started to build on existing rock outcrops and reefs to create 2,900 acres of new land.

Vietnam and the Philippines have undertaken similar ventures, but China has outpaced every other country combined. Sand is pumped up from the sea floor and spread across islands and even the live coral of submerged reefs that are then concreted over to become bases capable of providing docks for ships and runways for planes.Military runways have been built on Mischief Reef and Subi Reef. In other words, the Chinese have militarized the disputed islands.

Pivot to Asia

China’s claim to Scarborough Shoal in its dispute with the Philippines lacks any connection with current laws of the sea; I would interpret it as a claiming of world power status and importance.

The Chinese look around the region and see the projection of U.S. power: U.S. bases in South Korea, Japan, a nuclear submarine fleet, a military presence in Philippines and Australia and a fleet of super carriers able to project power and influence. The Chinese see the significant military and naval presence in the region as a threat to their regional power status.

The U.S. is the only country capable of proving a credible counter force. The U.S. response is sometimes referred to as the “Pivot to Asia” announced in 2011. It includes an increase in U.S. Navy assets in the Pacific, a planned deployment of 2,500 marines to Darwin, Australia, as well as a reassurance to regional allies to keep the South China Sea free for navigation and trade. The U.S. Navy has undertaken maneuvers in the region to drive home two points: these are open waters and the U.S. is still a credible force in the region.

In October 2015 a U.S. warship passed within 12 nautical miles of a China artificial island. A U.S. guided-missile destroyer passed through the disputed Paracel Islands in January 2016.

Troubled waters

The U.N. ruling will likely create more problems than solutions. Interpreted by China as a U.S.-inspired power move, it will increase rather than decrease geopolitical tensions.

Yet, conflict between Washington and Beijing can be managed. There are vast areas of mutual economic interest and shared global objectives.

A greater fear is that a local event can spin out of control. An overzealous Chinese lieutenant fires upon a U.S. ship; a U.S. destroyer rams a Chinese fishing boat. A U.S. plane is accidentally shot down by a surface-to-air missile from a disputed island. At the local level the potential for conflict grows to dangerous levels. And often it is events at the local that can influence the global.

Professor, School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. This article was first published on The Conversation and can be found here.