In the places where commemorations are tolerated, the Tiananmen Massacre is widely remembered through music.

The main candlelight vigil, held every June 4 in Victoria Park, has the format of a well-rehearsed concert and the singing of protest songs is an integral part of the solemn ceremony.

Not all of these songs, however, hark back to the days of the demonstrations. Last year, the late Roman Tam’s 1984 patriotic hit Chinese Dream was removed from the Victoria Park setlist. To reflect recent developments, it was replaced by Raise the Umbrella, an anthem of the Occupy movement. University students and localist groups, who organise separate June 4th demonstrations, have even eschewed music as a method of resistance altogether.

Back in 1989, many of the songs heard in Beijing were actually socialist anthems, and the most widely sung was The Internationale. For the post-Cultural Revolution generation of mainland Chinese, these anthems represented idealism in a time of uncertainty. Although they were appropriated as a form of protest, after the crackdown they quickly lost their connotations with the student movement. Against a backdrop of shifting values and allegiances, how has the musical legacy of the Tiananmen Square Massacre evolved over the years?

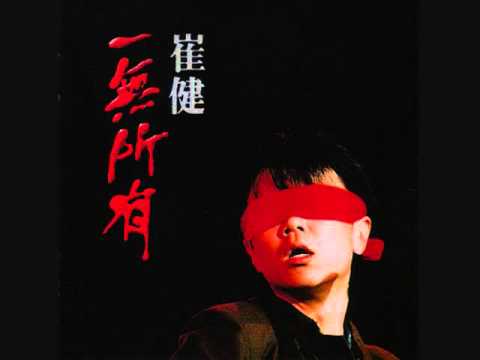

Nothing to My Name (一無所有) – Cui Jian (崔健) (1986)

“I have given you all of my aspirations, I have given you all of my freedoms. Yet you still laugh at me for having nothing to my name…”

Known as the “Godfather of Chinese Rock”, Cui Jian’s music flourished in – and very much embodied – the increasingly liberal and individualistic atmosphere in China in the late 1980s. Universities had been reopened, economic reforms were underway, and progressive factions within the party had taken control. Yet the sense of optimism was accompanied by increasing inequality, corruption, and the fundamental bankruptcy of socialism as an ideology. Ten years of destructive totalitarianism in the Cultural Revolution – and the rapid unpredictable changes that followed – left many young people, materially and spiritually, with nothing to their name.

See also: Full coverage of the 1989 commemorations.

Originally a trumpeter with the Beijing Philharmonic Orchestra, Cui infused Chinese influences into rock music, and made his breakthrough in 1986 with the rousing Nothing to My Name. Although never overtly critical, his performances were always subversive: he dressed in military uniform, donned a Communist-red blindfold, and named his first LP Rock and Roll on the New Long March. At the height of the student demonstrations in May 1989, Cui frequently played at Tiananmen Square. He was spared from the crackdown that followed.

After years of being unofficially banned from playing at major venues, Cui has been welcomed back into the mainstream. In 2014, state broadcaster CCTV reportedly invited him to play at its annual New Year Gala, although he was rumoured to have refused after discovering he would have to censor his lyrics. Although Cui is still closely associated with 1989, he no longer speaks openly about it. “This is self-imposed ideology, self-imposed censorship,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

99 Bends of the Yellow River (天下黃河九十九道灣)

“How many bends are there on the Yellow River? And on each bend, how many boats? And on each boat, how many oars?”

Musicians were not the only ones who stepped into uncharted waters. In 1988, writer Su Xiaokang and university professor Wang Luxiang produced River Elegy, a six-part documentary aired nationally on CCTV. Using the Yellow River as a metaphor, the film was an unprecedented attempt to reflect upon Chinese civilisation, criticising its tendency towards irrational idolatry, and predicting the triumph of Western civilisation.

Each episode opened with the distinctive bellowing of a Shaanxi folk singer. “How many bends are there on the Yellow River?” – it was a rhetorical question to which there was, symbolically, no rational answer.

After the massacre, River Elegy was banned, and its two producers became targets of the government crackdown; 99 Bends of the Yellow River is the only segment of the documentary that remains unscathed, and it is now an eerie reminder of the philosophical movement – if there ever was a coherent one – that underpinned the student demonstrations of 1989.

Descendants of the Dragon (龍的傳人) – Hou Dejian (候德健) (1978)

“The sound of gunfire broke the silence of the night, besieged on all fronts by the sword of dictatorship…”

Only 27 years ago, demonstrators from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong were united ideologically through patriotism, and musically through its well-known theme song, Descendants of the Dragon.

Whether living under the Communist, Nationalist or colonial governments, most people inevitably identified as Chinese. Through its proud and defiant lyrics, Descendants of the Dragon reminded listeners of a humiliating century of invasions and injustices in the country’s history. Composer Hou Dejian, originally from Taiwan, had written the song in protest to the United States in 1978, when it switched diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China. Yet five years later, Hou inexplicably deserted the island – illegally at the time – for the mainland.

In 1989, when Hou found himself in the midst of the upheaval in Beijing, he sided with the demonstrators. He participated in a hunger strike at Tiananmen Square, and flew to Hong Kong to perform his song at the Concert For Democracy In China, a marathon event featuring all of the city’s famous singers and entertainers. Following the crackdown, Hou was deported to Taiwan, and he has since faded from the limelight.

The Last Gunshot (最後一槍) – Cui Jian (崔健) (1987)

“A stray bullet strikes my chest, and my life flashes before my eyes… If this is to be the last gunshot, I will gladly accept this honour…”

One of the most evocative Tiananmen anthems, The Last Gunshot is a slow-motion soundtrack to death, juxtaposing regretful lyrics with repetitive, emotionless chords. But it was in fact written in 1987, when Cui Jian was inspired by the bloodshed on the Sino-Vietnamese border. The two countries fought in a month-long war in early 1979, when the People’s Liberation Army marched dozens of kilometres into Vietnam, and skirmishes continued until 1990. Following the massacre, however, the song took on a different meaning.

The Last Gunshot was not immediately banned, but a censored album version released in 1991 was almost unrecognisable from the 1987 original. Cui began singing in the fourth of five minutes in the track. All of the lyrics – save for three lines – were removed, effectively rendering the song a baffling instrumental. Thus began the government policy to clear all traces of the massacre from collective memory.

Blood-stained Glory (血染的風采) – Chen Zhe (陳哲) / Su Yue (蘇越) (1986)

“Perhaps, one day, I will fall asleep and never wake up… Would you believe that my remains have become part of the mountains? If it is to be so, do not grieve, for the flag of the Republic is stained with the glory of our blood…”

Like The Last Gunshot, Blood-stained Glory dates from before 1989, and was originally written in memory of the soldiers who lost their lives in the Sino-Vietnamese Conflict. However, it was a state-approved, richly-orchestrated socialist anthem extolling sacrifice for the country, instead of an individualistic, introspective rock song. Among its first performers was disabled war veteran Xu Liang, who deeply moved viewers of the 1987 CCTV New Year Gala. The song was therefore never meant to be subversive, until it reached Hong Kong at the height of the student demonstrations.

Arguably, Blood-stained Glory has now become the anthem most commonly associated with commemorating the Tiananmen Square Massacre. It became a staple of the performances of the late Hong Kong diva Anita Mui. Alongside Cui Jian’s Nothing to My Name, it also won RTHK’s Outstanding Mandarin Song Award in 1989. The ceremony was highly politicised, and the awards were presented by pan-democrat figurehead Szeto Wah and then-journalist Claudia Mo Man-ching. The song is repeated at every annual Victoria Park vigil to this day.

The Great Wall (長城) – Beyond (1992)

“Imprisoning the ancient empire, imprisoning the truth behind the events, imprisoning our halcyon days, imprisoning our desires and ideals…”

Legendary Hong Kong rock band Beyond were not only admired for their technical brilliance, but known as a perennially politically conscious group. They recorded anti-war anthems, paid musical tribute to Nelson Mandela, and were a high-profile act in Hong Kong’s Concert For Democracy In China in May 1989.

Yet by the time they released The Great Wall in 1992, the Tiananmen crackdown had ended, Deng Xiaoping had restarted economic reforms, and censorship of the massacre was well underway. Using the Great Wall as a metaphor, the song was Beyond’s subtle protest at the way the Chinese authorities were attempting to keep the populace ignorant of the events.

Other artists, like Tat Ming Pair with their single Ask the Gods, also expressed their outrage through similarly indirect and subdued lyrics, making no references to Tiananmen or even to modern China. After all, Hong Kong was anxiously counting down – first in years, then in months – to the handover of sovereignty.

Democracy Will Prevail (民主會戰勝歸來) – VIIV (2012)

“Democracy will prevail, for a new wave will rise from the sea and take up the mantle…”

Two decades later, the significance of the Tiananmen Square Massacre in politics has changed. Calls to vindicate the massacre and introduce democracy in China have fallen on deaf ears, and appear more untenable with each passing day. January 2011 saw the death of Szeto Wah, which sparked debates on how to pass on the mantle of remembrance to future generations. In despair, Hong Kongers began to limit their ambitions for political reform to their own city.

It was in this context that Democracy Will Prevail, written by the band VIIV – June 4th in Roman numerals – surfaced on YouTube. A simple but catchy piece, it asked listeners whether they were, by now, “used to the slaughter” and had “forgotten how it felt to be burnt by hellfire”. The song urged the new generation to take up the struggle for democracy, and was quickly introduced at the annual Victoria Park vigil.

As strong as the message sounded, it was no longer compatible with the aspirations of an increasing number of Hong Kongers. Localist groups responded with a heavy metal cover version of the song, titled The City State Will Prevail (城邦會戰勝歸來), criticising the pan-democrats, the middle and upper classes, and foreign imperialists for their lack of action. There are now several competing narratives that seek to explain Hong Kong’s past and present, and each has its own vision for the city’s political future.

Days Without Smoking (沒有煙抽的日子) – Tom Chang (張雨生) (1989)

“If you don’t have a cigarette, draw a matchstick, light up your helplessness, and smoke the droplets of rain that will never be seen again…”

Wang Dan was a 20 year-old student of Chinese history at Peking University, writing poetry and editing several publications, when he threw himself into the course of history in 1989. He camped out at Tiananmen Square, participated in a hunger strike, and worked night and day to organise his fellow students. Previously a smoker, at the height of the demonstrations, he did not even have the time to light up a cigarette.

Following the massacre, Wang found himself as one of 21 student leaders wanted by the authorities, and was forced to flee south. Along the way, he published Days Without Smoking – a poem recalling the peaceful, quiet life that he missed – under a pseudonym. But before he could reach safety, he was arrested on July 1st, and spent the next four years in prison. Across the Straits, the words were picked up by Taiwanese songwriter Tom Chang, and set to music. Chang reportedly visited Wang after his release in Beijing, in order to pay US$4,000 in royalties.

Today Wang lives in exile as a professor in Taiwan, while Chang died in a traffic accident in 1997. Still, Days Without Smoking is remembered as a highly personal, introspective testament to the Spring of 1989, a fleeting but unique and pivotal moment in modern Chinese history.