It is too early to tell if the government’s move to ban protest song Glory to Hong Kong, including online, would result in Google becoming unavailable in the city, a data scientist has said.

A Hong Kong court adjourned a hearing of an application from the Department of Justice for an interim injunction and injunction banning the distribution of the song with criminal intent on Monday. An industry group and a US-based consultancy have raised concerns that if the injunction were to be granted, it could prompt tech firms such as Google to become inaccessible in the city.

Data scientist Wong Ho-wa told HKFP on Monday that it was “too early” to predict what Google’s future in the city looked like, and that it would also depend on the company’s existing content deletion policies.

“If they do not plan to obey [if the ban is passed], then we will have to see how the government responds,” Wong said.

Authorities filed a writ last Tuesday seeking to ban the “broadcasting, performing, printing, publishing, selling, offering for sale, distributing, disseminating, displaying or reproducing [Glory to Hong Kong],” including on the internet, with a secessionist or seditious intent, or with the intent to violate the national anthem law.

It also sought to restrain anyone from “[a]ssisting, causing, procuring, inciting, aiding and abetting others” to commit those acts, and “[k]nowingly authorising, permitting or allowing others to commit or participate in any of the [aforementioned] acts.”

While the writ does not name the search engine, the government’s move came after multiple mix-ups that saw Glory to Hong Kong played in place of China’s national anthem, March of the Volunteers, at international sporting events.

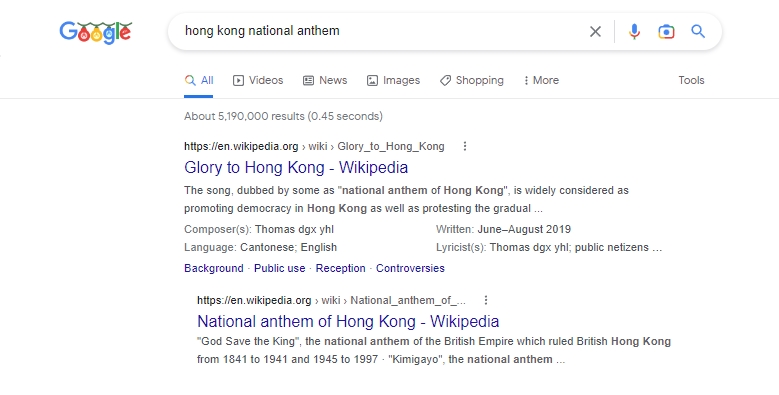

On Google, Glory to Hong Kong is among the top results when the term “Hong Kong national anthem” is searched. The tech firm has not acted on authorities’ calls to change search results to reflect March of the Volunteers as the rightful anthem.

The Hong Kong Internet Service Providers Association (HKISPA) told Young Post last Friday that the responsibility of enforcing the ban could fall on service providers, and since it was hard for providers to block specific content, the result might be a blanket block on of some or all of Google’s services.

A director at US-based consultancy Eurasia Group, meanwhile, said in an interview with Bloomberg on Monday that pressure on tech firms could lead to companies withdrawing services from the market, much like the Google search engine’s exit from mainland China in 2010.

Wong added that it would be difficult for search engines like Google to “100 per cent” comply with such an order.

“They would need to always be actively monitoring,” he said, adding that most of the time, Google only removed content – such as pirated videos – when it received a report.

HKFP has reached out to Google and the HKISPA for comment.

Google a ‘passive host’

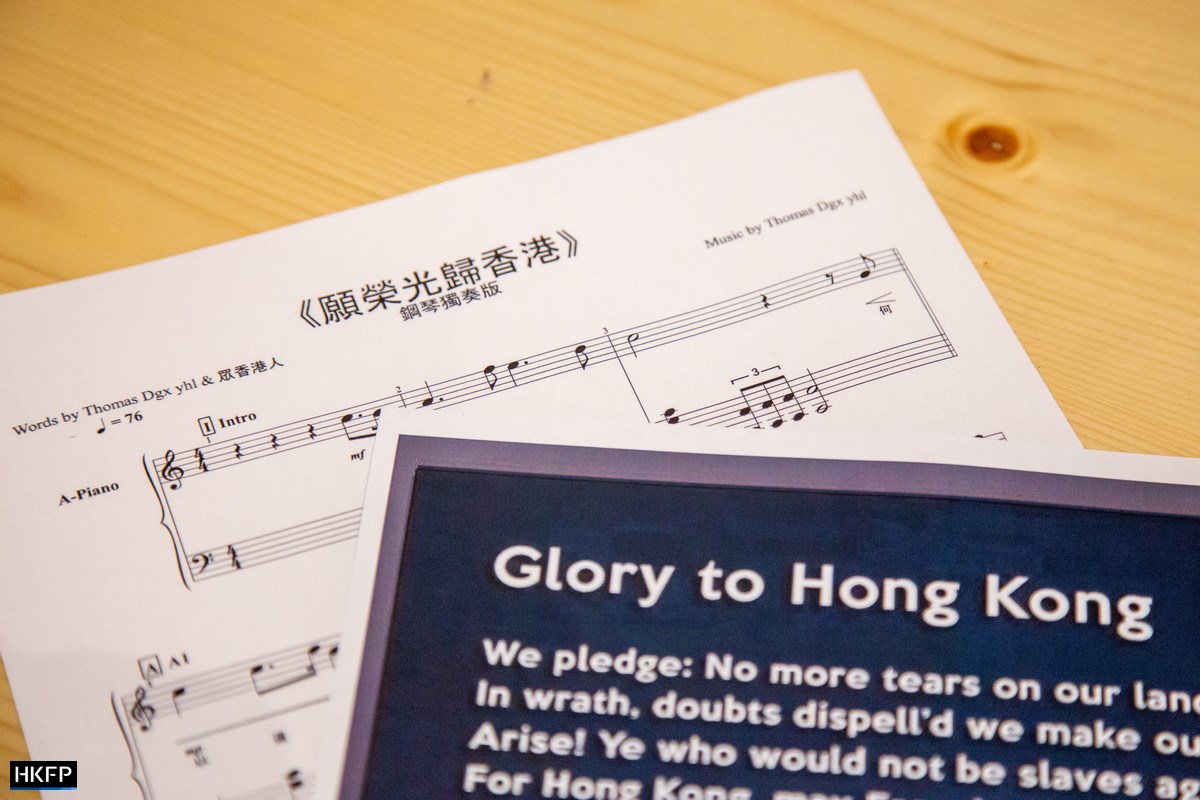

Glory to Hong Kong was written by pro-democracy supporters in 2019 and soon became an anthem of the extradition bill protests and unrest. Condemning the anthem mix-ups at sporting finals, the government has said the song was “closely associated with violent protests and the independence movement in 2019.”

While some protesters supported the city’s independence, it was not a key demand of the demonstrations.

The song contains the phrase “liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,” which the government said was ruled in the city’s first national security trial to be secessionist.

Wong said that if the injunction passes, users based in Hong Kong could theoretically still access blocked content relating to Glory to Hong Kong if they used a VPN.

“But I must make a disclaimer. If you use a VPN to bypass and your intent is known, it could be a legal risk,” he said.

Stuart Hargreaves, an associate professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s law school, told HKFP that he believed the injunction’s target were people the government could identify as sharing the protest song.

“[The government] may try and request that tech companies that host the song remove the material, but I expect that most would refuse on the ground that the injunction itself does not make the song illegal,” he said.

Hargreaves added that he doubted the tech companies themselves would be found in breach of the injunction as they were “simply” a “passive host” who lacked the “requisite intent to incite sedition or mislead as to the nature of the song.”

If the government passes a law criminalising Glory to Hong Kong, however, Hargreaves said he thought large tech companies would prevent access to it for Hong Kong users.

“[Google] has remove[d] material around the world in response to varying local laws, so this would be nothing new,” he said, citing the example of Google barring access to information in Germany relating to Holocaust denial as it is a crime under the country’s laws.

In the last half of 2022, the Hong Kong government requested that Google remove 183 items, according to the firm’s transparency report. Google refused almost half of the rquests.

The government cited national security as the reason for requesting removal in 55 of the cases.

A ‘serious infringement’

During Monday’s hearing, a Department of Justice representative said the injunction was aimed at people who “are conducting or intending to conduct” the distribution of Glory to Hong Kong with the intention of inciting secession, sedition, or to violate the national anthem law.

The administration also sought to bar the facilitation and authorisation of those acts.

Specifically, the government is also seeking to ban 32 videos of the song on YouTube. In a statement published on Monday, the publishers – who do not appear to be based in the city – of some of the videos said the attempt was a “serious infringement on the basic rights and freedoms” of Hong Kong people.

“The publishers fail to comprehend how the song “Glory to Hong Kong” poses a threat to national security,” the statement read. “It merely symbolizes the resilience of the people of Hong Kong in their pursuit of freedom and a democratic society.”

Hong Kong’s Court of First Instance adjourned the hearing about whether to grant the injunction banning the pro-democracy protest song to July 21.

Protests erupted in June 2019 over a since-axed extradition bill. They escalated into sometimes violent displays of dissent against police behaviour, amid calls for democracy and anger over Beijing’s encroachment. Demonstrators demanded an independent probe into police conduct, amnesty for those arrested and a halt to the characterisation of protests as “riots.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.