Of all the traumatic occasions in Wall-fare’s brief but eventful existence, the founder of the prisoners’ rights group will above all remember March last year – when tearful and panicky relatives of dozens of detained pro-democracy figures thronged its office appealing for help.

The 1,000-square-foot room was in tumult, recalled Shiu Ka-chun in an interview with HKFP to mark the first anniversary of Wall-fare’s decision to shut down under pressure from authorities.

Forty-seven pro-democracy figures – ex-lawmakers, activists and legal heavyweights – had been remanded in custody, accused of conspiracy to commit subversion under the Beijing -imposed national security law, following a four-day marathon bail hearing.

Families and friends were scrambling to get supplies for their loved ones behind bars or familiarise themselves with the drills for visitors – something they never expected to have to learn about. Others went to pieces, weeping and screaming.

It was the most unforgettable scene for Wall-fare in its nine months of existence, said Shiu, a former lawmaker.

“It was a humanitarian crisis,” the 53-year-old told HKFP. “Even though some were family members of [former] lawmakers, they collapsed very badly.”

The demand for organised support networks for prisoners in Hong Kong emerged in the aftermath of the 2019 anti-extradition bill unrest. More than 10,250 people have been arrested in connection with the months-long sometimes violent protests and hundreds were jailed. Scores of families were suddenly plunged into the unfamiliar bureaucracy of the city’s legal and penal systems.

Founded by Shiu in December 2020, Wall-fare became a leading source of material and practical support for jailed protesters and helped families navigate the complicated mechanics of local prisons. Until September last year, when the group announced it was disbanding, under pressure from the authorities and attacks by Beijing-backed media.

But the need for help for those imprisoned and their families remains. Now smaller, low-profile groups are attempting to fill the void.

Wall-fare was located just a few blocks from the Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, where up to 1,484 men are detained. Some are on remand pending trial, while others are adult prisoners, immigration detainees, appellants, civil debtors and those detained under the Drug Addiction Treatment Centres Ordinance.

Wall-fare’s office used to be filled with shelves full of M&Ms chocolates, Good Morning towels, bottles of Kao Feather shampoo, Tempo tissues, underwear and other prisoner essentials.

From the size to the style number to the colour and scent, each product had to meet the demanding specifications set by the Correctional Services Department. Otherwise, it would be rejected outright by corrections staff.

A limited quantity of these items could be handed over during visits. Many visitors counted on Wall-fare’s supply, as hand-picking prison products from regular shops could be very time-consuming. Some items could be found in grocery stores or vendors near prisons but prices were often marked up.

A full set of personal care products, stationery and other items could cost as much as HK$1,000 a month, Shiu estimated. His prisoner support group, however, had offered these supplies free of charge to around 150 inmates. Its main source of income was profits from selling coffee beans and other products. The group also offered vouchers in August 2021 to help cover the cost of purchasing prison supplies.

“[Wall-fare] was like a small grocery store that had a bit of everything. We had doctors, a dentist, a Chinese herbalist,” said Shiu, referring to other services the group provided to detainees. The ex-politician, who was himself jailed for eight months over the 2014 Umbrella Movement, had been a staunch advocate for prisoners’ rights but became less vocal after Wall-fare folded.

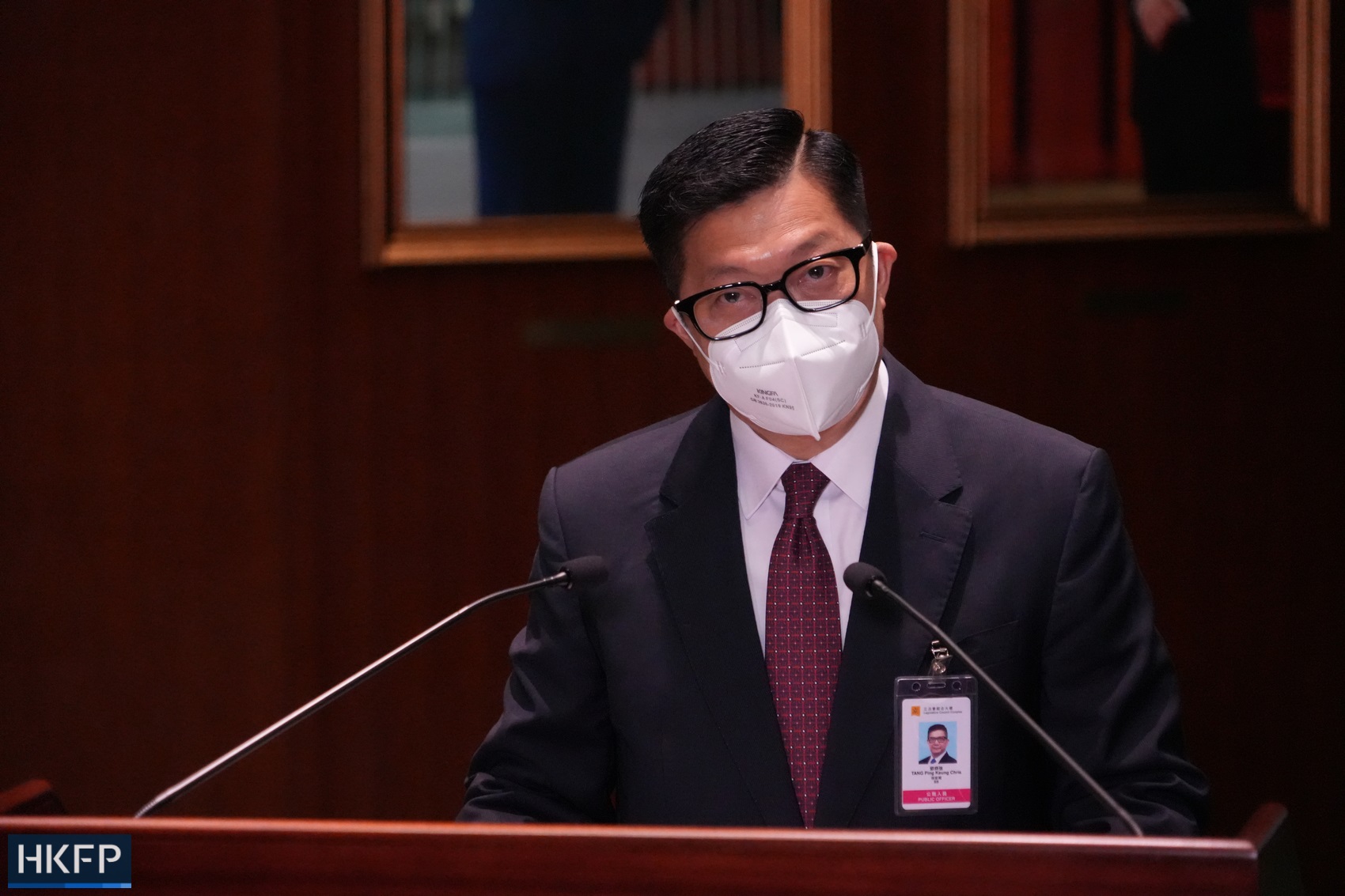

While Shiu saw the work of Wall-fare as humanitarian, Secretary for Security Chris Tang in September last year slammed organisations which assisted prisoners, especially those incarcerated for protest-related offences, as attempting to “build power” in jails.

The security minister named the 612 Humanitarian Relief Fund, which had announced it would halt operations by the end of October that year. He accused the group, set up to provide financial assistance for protesters arrested in 2019, as “dispersing the seeds of endangering national security” through writing letters to the prisoners. Tang also pointed to the supplies inmates received, such as chocolate and hairclips, saying that these could used by prisoners to gain “privilege.”

Two days after Tang’s criticism, the Wall-fare founder said the group would make fewer online calls to reduce “misunderstandings,” adding it had no intention and no power to monopolise the supply of prison items, as Tang alleged some organisations were doing.

Less than a week later Wall-fare, which was registered as a limited company, announced it was revoking its commercial license and shutting down. Standing outside the organisation’s office, reporters asked Shiu if he was worried this would leave inmates and their families with insufficient support.

The ex-legislator was silent for a few minutes, as tears soaked his face mask.

He eventually said: “We thought handing out a cup of cold water during summer and handing out a cup of warm water during winter was just very humble, humanitarian work. Unfortunately, we can’t even do this work today.”

Wall-fare was among some 50 civil society groups that shut down in the wake of the security law, including unions, churches, media organisations, protest coalitions and political parties. Some saw their leaders in custody pending trial, while others said they could not see a way forward in the current political climate.

Then-chief executive Carrie Lam said in August last year that the government respects civil society and denied any crackdown.

Families of detained protesters and activists were hit hard by Wall-fare’s shutdown. Emma, whose partner has been in custody for more than a year, said she was “really saddened” not only because a stable source of prison supplies was gone. What upset her the most was losing Wall-fare’s pen pal scheme, in which the organisation collected and mailed letters to the inmates.

“For prison supplies, I could use time and money to get them, but when you lose a pen pal, it is really gone,” the 21-year-old told HKFP, using a pseudonym for fear of repercussions.

“I also began to worry about the defendants in new protest-related cases [and their families]. Who can they turn to?” she asked.

One Released is among numerous small-scale organisations striving to maintain support for jailed protesters since Wall-fare folded. It has sold face masks, handmade soap, mooncakes, Christmas cards and other products to raise funds to purchase prison supplies. It also writes letters to inmates and visits them from time to time.

Volunteer Gwen, who requested an alias, said that although other groups had managed to take over some services Wall-fare had been providing, there remained a gap in coverage.

Efforts to support prisoners have become decentralised, as the remarks by the security minister last year were seen by other prisoner support groups as warning shots.

A question mark hangs over what kind of assistance might be deemed illegal under the security legislation, Gwen said.

“We often have to gauge by looking at who gets arrested to decide if we need to avoid doing certain work,” she said.

To stay out of the crosshairs, some organisations shun direct donations. Fung1seon3zi2, a group that organises for letters to be sent to imprisoned protesters and helps them find pen pals, told HKFP that people should simply send them stamps – not money – if they want to show support.

Ching, using a pseudonym, said her organisation also tried to mitigate risk by keeping its address confidential and only disclosing such details when someone asked privately. The volunteer in her early 20s admitted this could be futile, saying “not so good” people could still obtain their information by using a fake account to message the group.

“I don’t have other methods to make myself safer,” said Ching. “I think what I am doing is very mild already. I do have a political stance. But frankly, I haven’t incited anything,” she said.

While prisoners’ rights organisations in Hong Kong are working hard to sustain operations without attracting unwanted attention, a UK-based aid group for jailed protesters told HKFP that it did not feel the need to work in the dark.

Launched in the UK in October last year, Banyan Tree Aid is one of the few prisoner support groups that still appeals for donations. The organisation hands out monthly subsidies to families of imprisoned protesters, to help meet the cost of purchasing prison supplies and private meals, as well as transport costs for prison visits.

Last month the organisation, whose directors are based abroad, said it was currently supporting 87 families, with the aim of providing a monthly subsidy of HK$3,800. Accountant Thomas Fung, one of the founders, told HKFP the amount was based on an estimate that a detainee’s family would spend around HK$4,000 to HK $5,000 if they visited an inmate two to three times a week plus sponsoring private food.

But the size of the allowance would be subject to donations actually received, which was often below target, the 30-year-old said.

Banyan Tree Aid started operating around two months after the 612 Humanitarian Relief Fund announced it was shutting down. Five trustees of the defunct fund, including Cardinal Joseph Zen, pro-democracy barrister Margaret Ng and singer-activist Denise Ho, were arrested in May on suspicion of colluding with foreign forces. They have not been formally charged.

But the five and another man linked to the fund are set to stand trial this month over an alleged failure to register the fund as a society.

Fung said that while many Hong Kong-based prisoner support groups have gone “underground,” Banyan Tree Aid lists its founders and third-party financial supervisors. One of them is former British consulate worker Simon Cheng, who claimed he was tortured during his detention in China back in 2019 and was granted political asylum in the UK the following year.

“This platform relies on crowdfunding. If people don’t know who we are, it is difficult for them to trust us and be willing to make donations,” Fung said.

Asked whether he fears the authorities may declare Banyan Tree Aid’s operations unlawful and order the arrest of him and other founders, Fung said his team had considered the possibility of not being able to return to their home city.

“If we don’t do this work, I cannot face my conscience. We are safe here… we will do everything in our power to help,” he said.

To Gwen of One Released, the assistance she offers is reciprocal. Uncertain whether she herself will be charged following a protest-related arrest, the volunteer said she asked inmates for tips on how to survive in jail. She had tried to mimic life behind bars by restricting her diet to food available in prison, including M&M’s chocolates, raisin bread and oranges.

She also gave her mother a crash course on visiting arrangements just as she did for some family members of jailed activists, as well as made a list of books she wanted her family to send in if she were locked up.

But such preparations are never enough.

“You can never be fully prepared. Once you are still out there, you still have the feeling that you have a choice – you get to choose where you want to go, who you want to see. ”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team