Limitations on the right to trial by jury in Hong Kong are in the news. Under the national security law, the secretary for justice can dispense with a jury in cases endangering national security if they are satisfied that certain conditions exist.

The Court of First Instance, the court where jury trials are held, has no say in the matter. Nor has the person with most at stake – the defendant.

There was no public discussion in 2020 about the pro and cons of removing jury trial in the Court of First Instance for this limited class of offences before the introduction of the security law. Jury trials had featured in the Hong Kong legal landscape for over 150 years.

The institution was a constitutional building block in the Article 86 of the Basic Law: “The principle of trial by jury previously practised in Hong Kong shall be maintained.”

An override of a provision in the Basic Law is a big deal. It is, therefore, perhaps a good time to reflect on the importance of trial by jury and what is lost when the Secretary for Justice decides that a jury trial will not take place and that the fate of the accused is in the hands of three judges designated by the chief executive under Article 44 of the security legislation.

The first thing to say is that the right to a jury trial in Hong Kong has always been a meagre version of the equivalent right in England and Wales. There, where a jury can try an offence, a defendant has the right to choose that kind of trial over a trial before a magistrate sitting on their own.

Here, trial by jury has been at the option of the prosecution in all cases that can be tried with a jury. If the prosecution thinks that the penalty for the alleged crime might be imprisonment for longer than seven years, then it will choose a jury trial because only the Court of First Instance can impose sentences that long.

The sole exception to this rule is where a law fixes the penalty that can be set, such as a life sentence in cases of murder. In these cases, a jury trial is obligatory.

Only a tiny fraction of criminal cases end up in the Court of First Instance with a judge and jury. In cases where the prosecution expects a term of imprisonment on a conviction that is less than seven years but more than two years, it will opt for the case to be heard at the District Court for trial by a judge alone. Magistrates try all other criminal offences.

Another difference is that the jurors’ panel is only seven compared to 12 in England and Wales. The shortfall in numbers is because the pool of English-speaking jurors was limited when Britain administered Hong Kong and the courts used only English. As Chinese is now the language of choice in most criminal cases, there would be no problem in arranging juries of 12 in the unlikely event that the government extended the jury system.

However, even in its attenuated Hong Kong form, a jury trial offers a different kind of fair trial than a trial by a judge alone or a panel of judges. It lets a defendant have his fate determined by non-lawyers – the jury – who might do justice in the teeth of a strict application of the law. The ability of a jury to return a not guilty verdict against all the legal odds makes the institution unique and highly valued.

Lord Devlin was a British Law Lord in the 1960s. Before he became a judge in the UK’s highest court, the House of Lords, he had spent about fifteen years as a High Court judge, trying many cases with juries. He believed he had a good idea of how juries worked and what value they brought to the justice system.

He concluded a series of lectures entitled Trial by Jury in 1956, saying:

“The first object of any tyrant in Whitehall would be to make Parliament utterly subservient to his will; and the next to overthrow or diminish trial by jury, for no tyrant could afford to leave a subject’s freedom in the hands of twelve of his countrymen. So that trial by jury is more than an instrument of justice and more than one wheel of the constitution: it is the lamp that shows that freedom lives.”

Just 61 years later, another English senior judge, Baroness Hallett, reviewed Lord Devlin’s verdict on juries in giving the Blackstone Lecture for 2017. She concluded that the institution was not perfect.

For instance, jury trials were expensive. Sometimes, the expense seemed hard to justify. As long as an offence such as theft carried with it the right to trial by jury, a jury trial costing about £20,000 (HK$180,590) could be held at a defendant’s insistence to contest a trivial supermarket shoplifting charge over a £5 (HK$45) grocery item.

Baroness Hallett also noted that jurors sometimes misbehaved or went off on a tangent. She recalled the case of a female juror who was besotted with the prosecuting counsel. The juror sent him champagne and a note proposing a dinner date and was disappointed that the spoilsport judge discovered her romantic aspirations.

She also said that a common complaint in this internet age is that jurors cannot resist Googling the names of defendants and witnesses to discover more than they need to know to try a case according to the evidence presented in court.

The Baroness gave the example of a jury retiring to consider its verdict with a Ouija board. The jurors thought the answer to guilt or innocence in a difficult murder trial lay in trying to pierce the dusky veil of death with this spooky device to question the victim about the circumstances of his killing.

The judge concluded her talk by saying that she believed minor reforms to the jury system were in order, but that Lord Devlin’s remarks about juries still held good. She added, for good measure, the words of other famous English judges who all thought that jury trial was a good thing.

For Lord Camden, an 18th-century Lord Chancellor, it was “the foundation of our free constitution.” For Lord Eldon, another 18th-century Lord Chancellor, a jury trial was the “greatest blessing which the British Constitution had secured to the subject.”

More recently, Lord Denning, a Law Lord and Master of the Rolls between the 1950s and 1980s, said jury trial was “the bulwark of our liberties.” Finally, Lord Judge, a former Chief Justice who retired in 2013, called it a “safeguard against oppression and dictatorship.”

There is, clearly, more than just a sentimental attachment to trial by jury in England and Wales. It is worth digging into the past to explain why the subject of jury trial elicits this high praise.

Jury trial is a uniquely Anglo-Saxon legal institution. It originated in the 12th century when the common law began to take root in England. In 1215, the Magna Carta – a royal charter of rights – promised high-born barons a trial before their peers in legal disputes with the king.

However, the Magna Carta was not the reason juries began to be used to decide guilt or innocence in criminal trials. The democratisation of trial by jury was the indirect consequence of Pope Innocent III’s decision, made at almost the same time as the Magna Carta, to withdraw priests from officiating at trials by ordeal, which were the usual means of determining guilt and innocence.

A trial by ordeal meant alleged wrongdoers swearing to God before a priest they were not guilty of a crime and then, as a token of their innocence, seizing a red hot iron bar or plunging their hand into boiling water to recover a stone.

The wisdom of the day was that an innocent man might be expected to be relatively unscathed by the ordeal; a guilty man would bear the marks of guilt in his blistered hand or scalded arm.

Pope Innocent III thought priests’ presence at ordeals was unbecoming because they were officiating at a ceremony where there was blood-letting when making bets on God showing favour. He forbade them from participating. Without a priest, the oath of an accused meant nothing. Trial by ordeal was dead.

How to resolve the issue of guilt or innocence without an ordeal? Step in the newly minted jury to try issues of guilt and innocence with the guidance of one of the king’s justices.

It took another four hundred years for the jury to achieve its great constitutional significance when it was caught in a political contest between the king and its subjects.

In seventeenth-century England, there was no separation of powers, as we are told the position is now in Hong Kong. Only a very few people were eligible to elect members of parliament based on a property qualification, and they could be depended on to look after their selfish interests.

When the king was strong, parliament would do his bidding. The king’s will had precedence over independent law-making.

Judges had no security of tenure at this time. They held office at the king’s pleasure, and he could sack a judge at any time. As a result, some judges did their best to ensure that they guided jurors to reach the “correct” verdict – i.e. guilty – in cases where the defendants held unorthodox political views that were not acceptable to the Crown and its ministers of state.

There are reports of jurors being locked up without food and water until they returned an acceptable verdict. Judges inflicted huge fines on “obstinate” jurors.

Matters came to a head in the reign of King Charles II in 1670. Only members of the Church of England could hold public office and stand for election then. Catholics, Baptists, Jews and other religious dissenters, including Quakers, were excluded from public life because of their political unreliability.

Two Quakers, William Penn and William Mead, held a public prayer meeting in a London street when such meetings were banned unless the assembly comprised members of the Church of England. The state prosecuted them for unlawful assembly.

At the trial, Penn relied on common law freedoms and the rights in the Magna Carta. The trial judge gave these arguments short shrift and directed the jury that it was duty bound to bring in a guilty verdict.

The jury considered its verdict. Some jurors sympathised with Penn and Mead, who had behaved peacefully at the religious meeting. They found them guilty of “speaking in the street”, but refused to add the crucial words “in an unlawful assembly.”

The judge refused to accept this verdict. He ordered the jury to be “locked up without meat, drink, fire, and tobacco.” Eventually, after two days of uncomfortable sequestration, the jury came into court and returned a not guilty verdict.

The judge exploded. He could not return a verdict of guilty on his own. Instead, he fined the jury for returning a perverse verdict, i.e. one not acceptable to him, and ordered the jurors to be imprisoned until they paid a fine.

One of the imprisoned jurors, Edward Bushell, applied to the Court of Common Pleas for a writ of habeas corpus. He argued that the trial judge could not punish members of the jury for returning a verdict he did not like.

To the surprise of many, Sir John Vaughan, the chief justice, agreed with Bushell. He said a jury’s verdict was final, even though it might appear to be against the evidence or in opposition to the law as laid down by a judge.

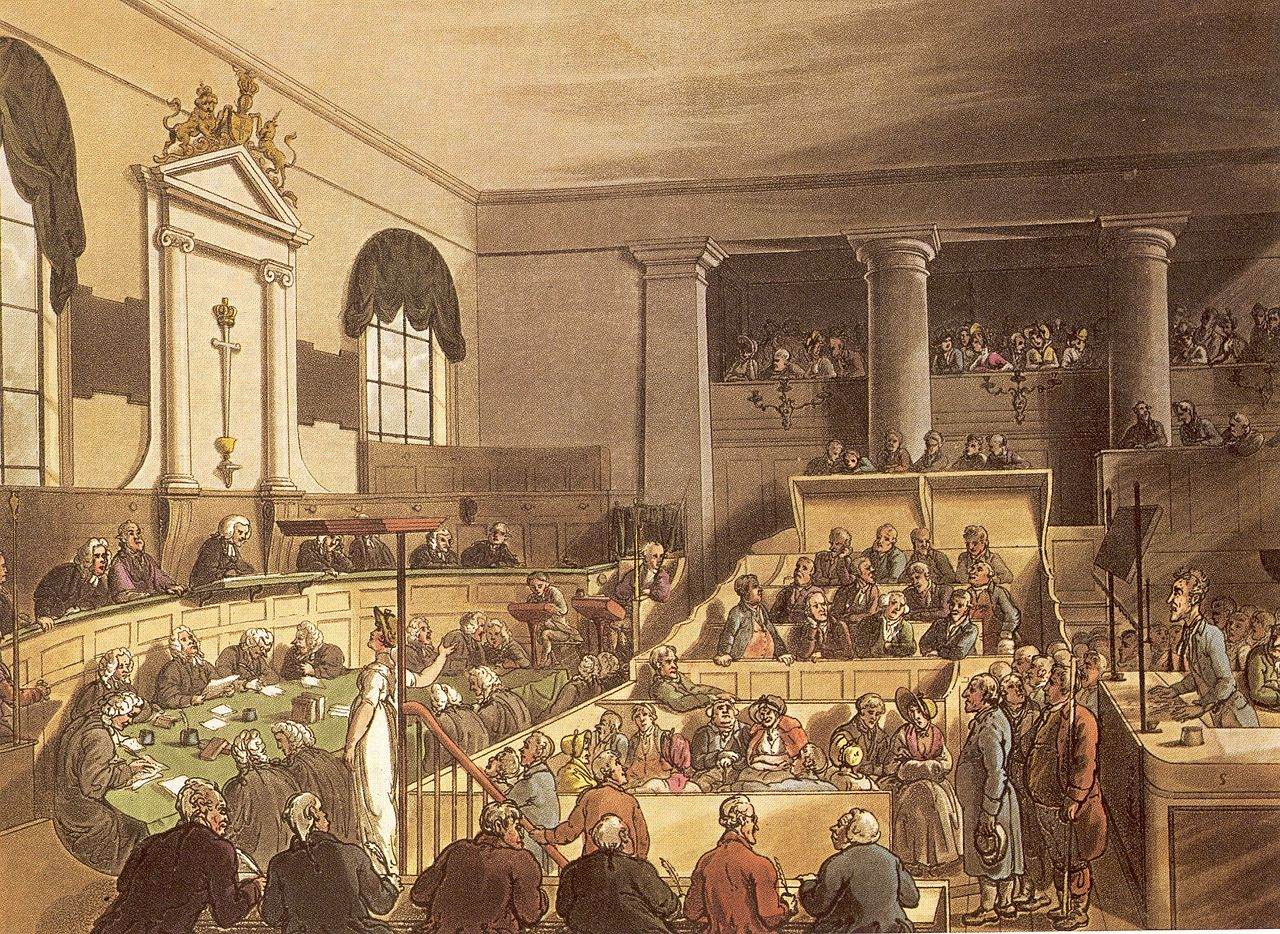

The supremacy of a jury’s verdict has not been questioned since Bushell succeeded in securing his release nearly four hundred years ago. To commemorate the jury’s defiance, a plaque is fixed on a wall in London’s principal criminal court, the Old Bailey.

It reads: “Near this site William Penn and William Mead were tried in 1670 for preaching to an unlawful assembly in Grace Church Street. This tablet commemorates the courage and endurance of the jury, Thos Vere, Edward Bushell and ten others who refused to give a verdict against them although locked up without food for two nights and were fined for their final verdict of not guilty.”

Since Bushell’s case, there have been many in which evidence of guilt seemed overwhelming, and juries have returned not guilty verdicts because it seemed the right thing to do.

Many of these acquittals happened in the second half of the eighteenth century. There was growing pressure to reform parliament and extend the franchise to working men. Juries protected men of conscience who wanted reform and spoke out about it by acquitting them of political offences like sedition and treason, to the frustration of the government of the day.

After the political franchise extension in the 19th century to give men the vote – women would have to wait until 1919 – English juries largely ceased to be involved in contests with the government over political issues stemming from limited political representation.

Juries would continue to show their displeasure towards prosecutions that, whatever the case’s legal merits, they thought to be oppressive or where the government was duplicitous.

An example of an English jury acquitting despite the evidence was the case of Clive Ponting.

Ponting was a civil servant with a conscience who served in the Ministry of Defence.

In 1984 he leaked documents about the sinking of an Argentine battleship, the General Belgrano, in the 1982 Falklands War. Over three hundred sailors, mostly conscripts, died. The official story was that the Belgrano presented an immediate threat to operations in Falkland Islands waters and that its sinking by a British submarine was necessary.

The official story was not true. At the time of its sinking, the General Belgrano was sailing away from the scene of military operations. It did not present an immediate military threat.

The police discovered Ponting was the source of the leak. The government prosecuted him for a breach of the Official Secrets Act of 1911 because the dossier on the sinking was classified.

A jury tried Ponting, who admitted the leak. The trial judge summed up the case against him in such a way as to suggest that the jurors had to convict him because the only excuse in law that Ponting could rely on was that disclosure was “in the interests of the state.”

The judge was disposed to say that the government had the final say in what matters its interests lay. Leaking government documents about wartime operations was not “in the interests of the state,” said the government.

Whether the judge was right or wrong about his legal view of the state’s interests, the jury was unimpressed with the prosecution’s case.

The prosecuting counsel was asking jurors to treat the falsification of facts as something that the government could hide from the public under the rubric of “state interests.” It troubled the jury members that the judge was inviting them to convict Ponting after exposing a patent lie.

The jury acquitted Ponting. Some lawyers said the verdict was perverse because it did not conform to the law. However, the general public feeling was that the jury did justice to Clive Ponting in not following the strong suggestions of the judge that it was virtually bound to convict him.

Lord Devlin gave the last word on juries in his lectures on the great eighteenth-century English jurist William Blackstone, after whom the law lecture given by Baroness Hallett was named.

Blackstone warned against getting rid of juries despite plausible arguments that no injustice would result if some cases were tried without them. He said this about the “convenience” of dispensing with them:

“And however convenient these may appear at first (as doubtless all arbitrary powers, well executed, are the most convenient), yet let it be again remembered, that delays and little inconveniences in the forms of justice, are the price that all free nations must pay for their liberty in more substantial matters; that these inroads upon this sacred bulwark of the nation are fundamentally opposite to the spirit of our constitution; and that, though begun in trifles, the precedent may gradually increase and spread, to the utter disuse of juries in questions of the most momentous concern.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team