Five Hong Kong speech therapists have been found guilty of breaching the colonial-era sedition law by printing a series of children’s books about sheep and wolves. The publications were said to have spread separatism and incited hatred against the authorities.

District Judge Kwok Wai-kin on Wednesday convicted Lorie Lai, Melody Yeung, Sidney Ng, Samuel Chan and Fong Tsz-ho of conspiring to print, publish, distribute and display three books with seditious intent between June 2020 and July 2021.

The five executive committee members of the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists, all of whom had denied the charge, could face up to two years behind bars. They will return to court on September 10 for mitigation and sentencing.

Following a three-hour delay, Kwok said only that the defendants were convicted but did not give the reasons for their convictions. He said people could refer to the reasons in his verdict, which was uploaded to the Judiciary’s website around 15 minutes after the hearing ended. Journalists also received a document summarising Kwok’s judgement after the hearing.

In the 67-page-long verdict, Kwok said the sedition offences did not impose any more restrictions on the right to freedom of expression and publication than necessary for safeguarding national security and and public order.

The existing law does not bar anyone from saying or publishing whatever they want – including criticism of the authorities – the judge said, given that they do so without a seditious intention.

Citing Article 2 of the national security law, Kwok said one must recognise that Hong Kong is an inalienable part of China, and that Hong Kong only enjoys a high degree of autonomy, rather than complete autonomy, when they exercise their rights and freedom.

“When this simple rules are adhered to, it is unlikely for anyone to commit an offence of sedition unwittingly,” Kwok wrote.

Broad brush, deep impression

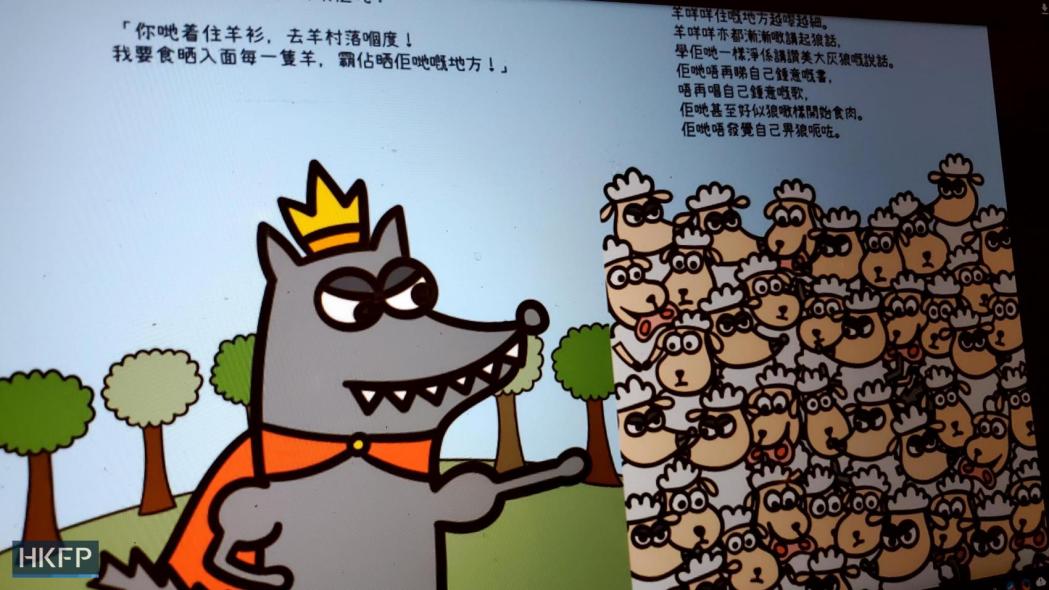

In determining whether the children’s books were seditious publications, Kwok said he read the three books himself, bearing in mind that the target reader could be as young as four years old.

The books contained a “broad brush but deep impression” that the wolves were evil aggressors, while the sheep were kind but oppressed, the judge wrote.

While the defence argued that the story was “just a fable,” Kwok said the first book, in its foreword, made reference to the “anti-legislation movement,” which he said was a clear reference to the anti-extradition bill movement.

By implying that Chinese government were wolves and the Hong Kong chief executive was a wolf who “masqueraded as a sheep” and was instructed by the “Wolf-chairman,” Kwok said the storyline of the first children’s book would lead young readers to believe that the Chinese government was “coming to Hong Kong with the wicked intention of taking away their home and ruining their happy life with no right to do so at all.”

“The publishers of the Book clearly do not recognize that the PRC has legitimately resumed exercising sovereignty over HKSAR, but the children will be led to hate and excite their disaffection against the Central Authorities,” Kwok wrote.

Children who read the book would also be led to believe that the leader of Hong Kong was sent by the Chinese authorities “with the ulterior motive of hurting them,” the judge wrote, adding readers would be led to “look down” on the chief executive “with contempt.”

Kwok went on to say that the picture books would make young readers believe that “if they are not obedient, they will be sent to prison,” while the ill-fated extradition bill was depicted as a tool to “supress dissenting Hong Kong residents” and subject them to “arbitrary arrests” or even be jailed in China.

“The publishers therefore lead the children not to trust the administration of justice in Hong Kong and look down upon the police, the prosecution and the court with contempt,” the judgement read.

Kwok ruled that the second book would lead children to think that the 12 Hongkongers who tried to flee to Taiwan while facing criminal charges or investigation were “victims of oppression and unfair prosecution,” and that the group had been “closely monitored by the wicked force to be taken to prison.”

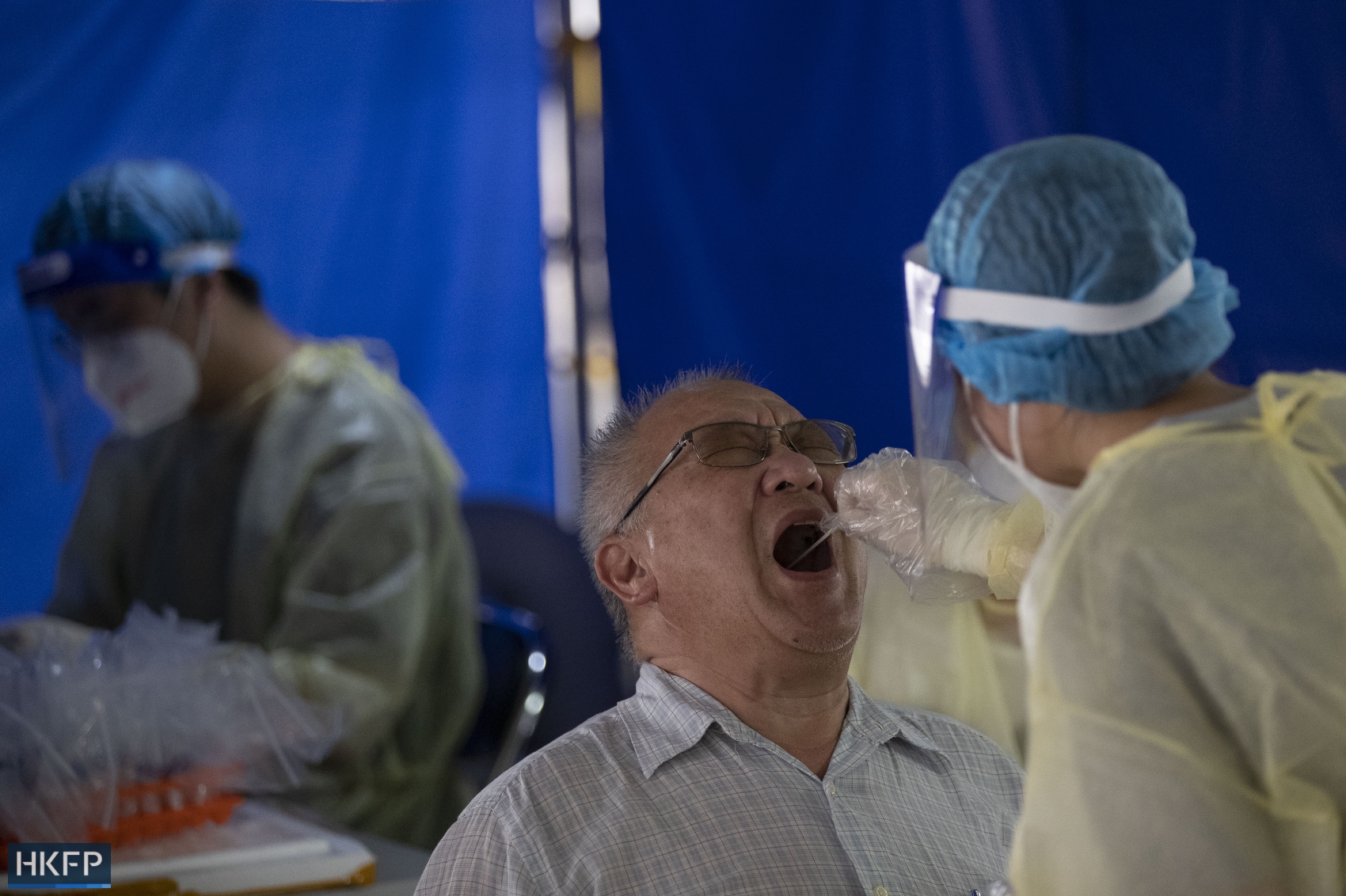

The third book, on the other hand, would lead young readers to believe that the government deliberately allowed people from China to “make their home dirty and spread the pandemic,” the judge ruled, saying it amounted to inciting discontent among Hong Kong residents.

The judge dismissed the argument from the defence that the open question placed at the end of each book was proof that the publication did not intend to “indoctrinate” the minds of the young readers. It was “hypocritical” to say that children were allowed to keep an open mind, he said.

“It is patently clear from the structure of each book that the thinking of the children is to be guided in a particular way when the story is being told… the so-called open answer from the child himself is no more but a guided answer,” the judgement read.

Kwok also ruled that all defendants participated in the conspiracy through their positions in the union, which the judge said was “clearly set up for political purposes.”

With hardcopies of the books found in all defendants’ possession when they were apprehended, as well as their access to the union’s website and social media accounts, Kwok said all of them knew the contents of the books and had agreed to published them.

Crimes Ordinance time limit

The defence had challenged that the charge laid did not fall within the time limit set out in the Crimes Ordinance, which stated there should be no prosecution for a sedition offence except within six months after the offence was committed. The conspiracy element was also time-barred.

The defence had said the charge was written as one conspiracy in connection with three books, and the offence was complete when the agreement was made.

But Kwok rejected such submissions, saying that the conspiracy in the present case was an offence “continuing throughout” the period since the first book was published on June 4, 2020 until July 22 last year, when the five defendants were arrested.

He cited the printing and publication of the books, as well as a reading session of the books held by the speech therapists. The conspiracy therefore did not merely cover the printing of the books, but also their publication, distribution and display.

“It is therefore beyond any shadow of doubt that the conspiracy entered into between the defendants had not come to an end before their arrest,” Kwok said.

‘Seditious’ children’s books

The children’s publications allegedly alluded to the 2019 anti-extradition bill unrest, the detention of 12 Hong Kong fugitives by the Chinese authorities, and a strike staged by Hong Kong medics at the start of the Covid-19 outbreak.

The defendants, who have been held in custody for more than a year, were said to have “indoctrinated” readers with separatism, incited “anti-Chinese sentiment,” “degraded” lawful arrests and prosecution and “intensified” conflict between Hong Kong and China.

During the trial in July, prosecutors argued that sedition was a “very serious offence” which was tantamount to “treason.” Lead prosecutor Laura Ng said the legislation – last amended in the 1970s when the city was still under British colonial rule – had “long laid dormant,” but Beijing saw the need to apply the sedition law to safeguard national security following the 2019 protests.

The defence, on the other hand, denied the picture books had seditious intention. Lawyers representing the speech therapists criticised the recently resurrected legislation as having “wide parameters” and said it “lacked clarity.”

They argued that such offences could be misused to clamp down on dissenting voices, saying similar laws had been abolished or reformed in numerous jurisdictions.

Barrister Anson Wong, representing union secretary Ng, also cited a United Nations Human Rights Committee report, which said that the sedition legislation had an “overly broad interpretation.”

Sedition is not covered by the Beijing-imposed national security law, which targets secession, subversion, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts and mandates up to life imprisonment. Those convicted under the sedition law face a maximum penalty of two years in prison.

‘Disintegration of human rights’

Gwen Lee, Amnesty International’s China campaigner, said in a statement on Wednesday evening that the conviction was an “absurd example of the disintegration of human rights in the city.”

“Writing books for children is not a crime, and attempting to educate children about recent events in Hong Kong’s history does not constitute an attempt to incite rebellion,” Lee said in the statement.

“The Hong Kong authorities’ recent revival of colonial-era sedition charges to prosecute activists, journalists and writers is a brazen act of repression. No one had been charged with sedition since 1967 until the Hong Kong government began weaponizing these provisions to intensify its crackdown on freedom of expression.”

The campaigner also called for the abolition of the “archaic” law and the immediate release of the group.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team