Our Chief Executive John Lee urged young people in a recent speech to “tell the world a good story about Hong Kong whenever possible.” Which is no doubt something much to be desired.

But Hong Kong’s problem with the world is not so much a shortage of good stories as a surplus of bad ones. I realise that it is hard for a chief executive – buffeted by events, “advised” by Mother and besieged by people who think their interests coincide entirely with those of the city – to do much about this.

But there are some things which are still under the government’s control and which could reduce the flow of bad stories.

Let us start with a bad story which goes back 800 years. In 1215 the then King of England – another John, by coincidence – was cornered by a bunch of rebellious barons and persuaded to sign a charter promising improvements in government.

Of course, John repudiated it soon afterwards as having been extorted under duress, but it had his signature and seal on it so lawyers treated it as part of the law anyway. Most of the improvements concerned the rights and obligations of feudal vassals but a few fragments are still law.

One of them is the famous paragraph 39, which goes, translated from the Latin: “No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land.”

And from this arose the rule that anyone accused of a serious offence was entitled to a trial by jury. The other landmark – a case of unlawful assembly, oddly enough – came in 1670. In what is known as Bushel’s case, the jury acquitted the two defendants and the judge sent them to jail with orders to change their verdict.

Bushel, who was one of the jurors, appealed to a higher court and established that the jury has the exclusive right to return whatever verdict it thinks proper, regardless of the opinions of the judge.

There is rarely much discussion of jury decisions – it is actually illegal to interview a juror about what happened in the jury room – and while there are sometimes verdicts which appear a little inexplicable, most lawyers regard juries as no more eccentric in their decision-making than judges, though in different ways.

It is known that juries are somewhat more likely to acquit defendants than judges sitting alone – the usual alternative in England – but this does not mean they are prone to error. Judges who hear a lot of criminal cases often develop a certain cynicism about the usual defences.

The right to a jury trial was duly exported to Hong Kong and was among those rights commonly supposed to be secured by the Basic Law. Under the national security law it is no longer a right. If you are accused of a serious national security offence, the government has the option of dispensing with the usual jury and replacing it with three judges of its choosing.

The jury in the city’s first national security trial was replaced in this way, and the high-profile subversion case against 47 democratic defendants will also proceed without a jury. This is the sort of story that “the world” tends to take rather badly. If a jury trial is good enough for your common or garden burglar, rapist, murderer or whatever, it is not a good look to rule it out for one category of defendant. And the picked judges look a bit… shall we say, Hungarian?

And this is not necessary. The security law allows the jury to be replaced but it does not require it. The secretary for justice would no doubt be willing to heed a plea from his boss that this unlovely innovation should be sheathed for the time being. It may be that juries will be reluctant to convict in cases with a political flavour and we shall have to think again. But a few surprising acquittals would look better than setting a new global standard for kangaroo courts.

We can also consider another of King John’s promises, which goes like this: “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice.” Now justice is not yet for sale, and you can argue about whether it is denied, but what cannot be disputed is that it is now delayed. Another avoidable “bad story” involves political figures – sometimes aged or ill or both – being remanded in custody for months awaiting trial.

This again is enabled, but not required, by the national security law. The presumption that defendants will have bail is reversed. There is, however, no requirement that the prosecution should on every possible occasion oppose the granting of bail. Nor is there a requirement that the prosecution should take its own sweet time preparing a case.

Prosecutors in the UK are strenuously discouraged from keeping defendants in custody for more than six months. In Egypt, hardly a human rights haven, a prosecution which has not begun after two years is summarily dismissed, which counts as an acquittal.

This is a matter of policy and priorities, not law. Keeping people on ice for years awaiting trial is another “bad story” which does not go down well in “the world.” Prosecutors in other countries manage to work at higher speeds. They should be emulated.

Then there is the matter of political pollution in police work. Typical “bad story” this week. A man was busking in the Tung Chung bus station in April. Police turned up. He was playing an erhu, which is not everyone’s cup of tea. There had apparently been a complaint.

In due course he was arrested and charged with playing an instrument “in a public street or road save under or in accordance with the conditions of a permit from the Commissioner of Police.” This is apparently an offence under the Summary Offences Ordinance and I have committed it more times than I can remember. Who would have thunk it?

Wandering around Hong Kong you see buskers all the time. I have never heard of any of them being prosecuted. The bagpipe is an outdoor instrument often practised in the street. Likewise no interest from law enforcement. Occasionally a practising group will produce a noise complaint and we are just politely asked to desist and move on, which we do.

So why, you wonder, was 68-year-old retiree Li Jiexin introduced to the obscure corners of the Summary Offences Ordinance? Well magistrate Felix Tam – who acquitted Mr Li on the grounds that the prosecution had called no evidence of the absence of a permit, an essential ingredient of the offence – stressed that politics had nothing to do with justice and refused to allow any evidence of what tune Li was playing.

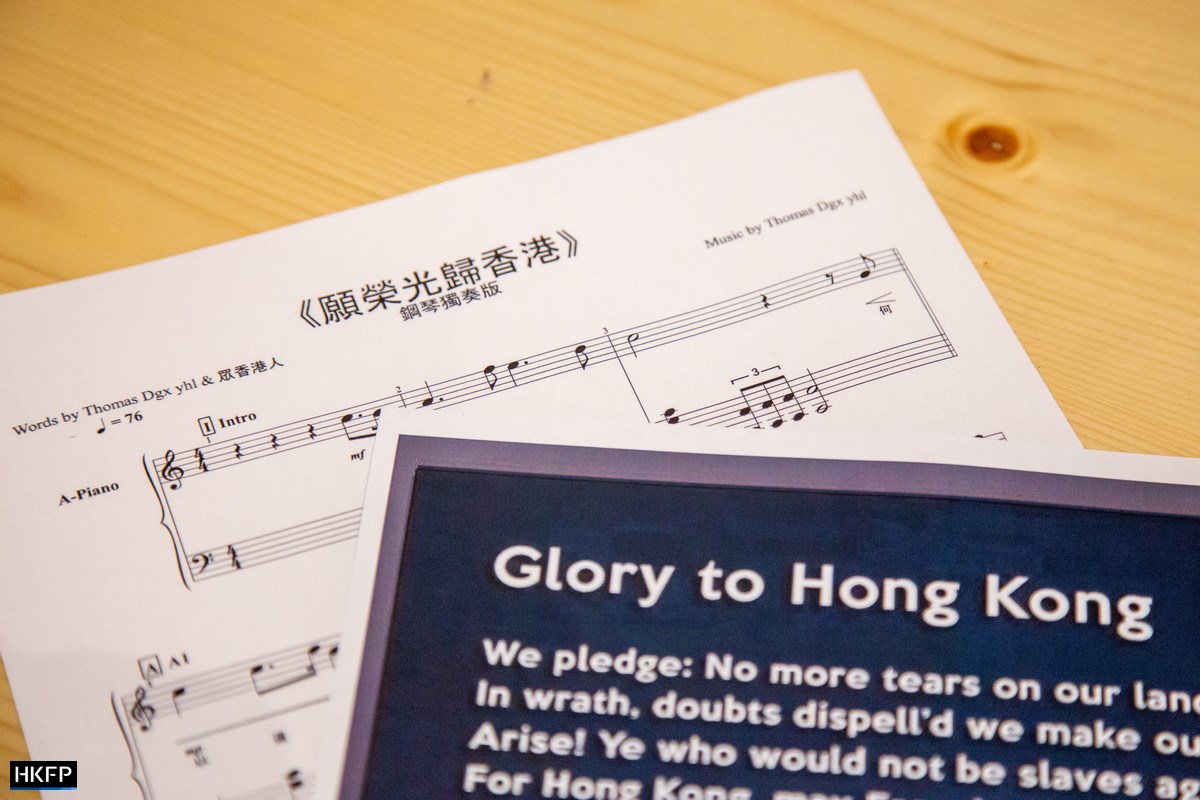

Very good. Still it seems that the thing which distinguished Li from other ordinary buskers unworthy of the attention of the police force is that he was playing the tune of Glory to Hong Kong, a popular protest song.

The weaponisation of obscure laws to suppress expression of which the government disapproves is another “bad story” which allows critics to depict Hong Kong as a place where the law is a tool of tyranny, not a protection for the public. Once again this is an option, not a requirement. Tell your boys to behave themselves.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.