Wong Wai-man, better known as Ah Man, used to carry a pile of union application forms in his backpack wherever he went. After the historic steel workers’ strike in 2007, the 66-year-old bar bender – with a full white beard to rival Albus Dumbledore’s from the Harry Potter series – founded a union and spent much of his time travelling between construction sites persuading others to join him.

“Not to brag, but when it comes to recruiting members, I’m an expert,” he told HKFP with a proud smile. The Bar Bending Industry Workers Solidarity Union had nearly a thousand members in its heyday.

However, it has less than a hundred now.

Although retired, Ah Man still teaches bar bending part time while overseeing the union. However, he said he no longer recruits like he used to. “After all, there are a lot of uncertainties under the political climate in Hong Kong these days,” he said.

“I don’t think I should ask people to join when I don’t know what lies ahead either.”

The Bar Bending Industry Workers Solidarity Union was a sub-union of the pro-democracy Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU), a large labour rights group that provided financial support, union secretaries and connections to its 78 sub-unions.

However, the 31-year-old HKCTU was one of dozens of civil society organisations that disbanded in 2021, after its chairperson Carol Ng was among the 47 democrats charged with “conspiracy to commit subversion” over an unofficial legislative primary held in July 2020.

The previous month, Beijing had inserted national security legislation directly into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution – bypassing the local legislature – following a year of pro-democracy protests and unrest. It criminalised subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts.

The move gave police sweeping new powers, alarming democrats, civil society groups and trade partners, as such laws have been used broadly to silence and punish dissidents in China. However, the authorities say it has restored stability and peace to the city.

According to prosecution documents released in the 47 democrats’ national security case, “unions” were one of the battlegrounds created by the pro-democracy parties. Ng has been accused of advocating a general strike during the 2019 protests and unrest.

Ah Man, a seasoned labour rights activist, said he thought that Hong Kong was unlikely to host another strike in the near future, since any labour rights movement could pose legal risks to its participants. As an example, he mentioned a warning received by the HKCTU about Covid-19 public gathering limits when it set up a promotional booth on Labour Day last year.

For Chan Fo-tai, though, there were still many injustices to fight in the construction industry, especially for women workers.

The former executive member of the Bar Bending Industry Workers Solidarity Union, who is widely known as the first female bar fixer in Hong Kong, said that she was denied many opportunities solely because of her sex.

“I spent a few years searching for a stable bar fixing job, but no one was willing to hire me just because I’m a woman,” Chan said.

Bar bending is an integral part of building development in Hong Kong, with benders responsible for creating rebars, the steel skeleton of structures used in concrete construction. However, the work is project based and most bar benders are employed as day labourers, meaning that they are not entitled to paid holidays, severance or other benefits that come with salaried roles.

Chan said that she was “pessimistic” that these benefits would be extended to day labourers any time soon. “The [bar benders’] union is in an awkward position. There’s not much they can do.”

Ah Man, too, said he did not intend to put forward more demands under this sensitive atmosphere. “The top priority of the union now is to stabilise itself,” he said.

The time when one can strike

Ah Man’s first encounter with the labour rights movement came in the 1980s, before he became a bar bender, when a strike broke out in the textile factory he was working in.

“The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions was actually doing a good job at the time,” he said, referring to the largest pro-establishment union in Hong Kong. “They even set up a temporary cafeteria for the workers near the factory.”

Ah Man said that striking was easier back then, as people were not afraid to act when their wellbeing was in danger.

His second moment of workers’ rights enlightenment occurred in the mid-1990s, when a worker was injured on a construction site Ah Man was overseeing. Exhausted because the subcontractor had denied his request for a second supervisor to share his work, Ah Man had turned away after dividing steel bars into heavy piles, when he heard a loud bang. Someone had put their steel bundle into an unfinished holder that had collapsed and broken another labourer’s leg.

“That is the biggest regret in my life,” Ah Man said. He still chokes up when talking about the accident. “I have always been left-leaning, but that accident made me want to work for labour rights even more.”

The following decade, Ah Man found his opportunity.

After the SARS outbreak in 2003, the city’s economy suffered and bar benders’ daily wages plunged from around HK$1,200 to HK$800, according to Ah Man and the labour rights outlet WKnews. By 2007, the economy had largely recovered, however, subcontractors tried to increase the working hours of bar benders from eight and a half hours per day to eight and 45 minutes, even though the daily wage had only risen by HK$30 to HK$50.

“One of the bar fixers was furious after seeing the notice [about the rise in working hours]. In just a few days, we decided to start a strike,” Ah Man said.

The bar benders’ demands included returning their working hours to eight hours per day – the standard for bar fixers before Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to China – and raising their daily wage to HK$950.

Ah Man was elected to be one of seven workers’ representatives tasked with negotiating with the subcontractors and the developers. The strike lasted for 36 days until September 12, 2007, when the employers’ representatives agreed to pay HK$860 for an eight-hour work day.

While some called the result a pyrrhic victory because of the enormous political and financial pressures placed on the strikers, Ah Man said his most important takeaway from the action was the need to set up a communication mechanism between the workers and the employers.

“During the negotiation, [the employers] told us they wouldn’t listen to a ‘nobody.’ That’s why I started the Bar Bending Industry Workers Solidarity Union – so that we wouldn’t be a nobody anymore,” Ah Man told HKFP.

He claimed that the strike and the union successfully opened a window for both sides to discuss welfare, at least in the first few years.

In 2010, the Bar Bending Industry Workers Solidarity Union successfully reached an agreement with the commerce union to allow construction workers to take an additional 15-minute break when the very hot weather warning is in force. It has long fought for better compensation claims after work-related injuries.

However, the union lost resources, members, staff and a venue after the HKCTU disbanded. Additionally, employers stopped inviting it to discussions. As a result, Ah Man said, construction firms have disregarded agreements and regulations.

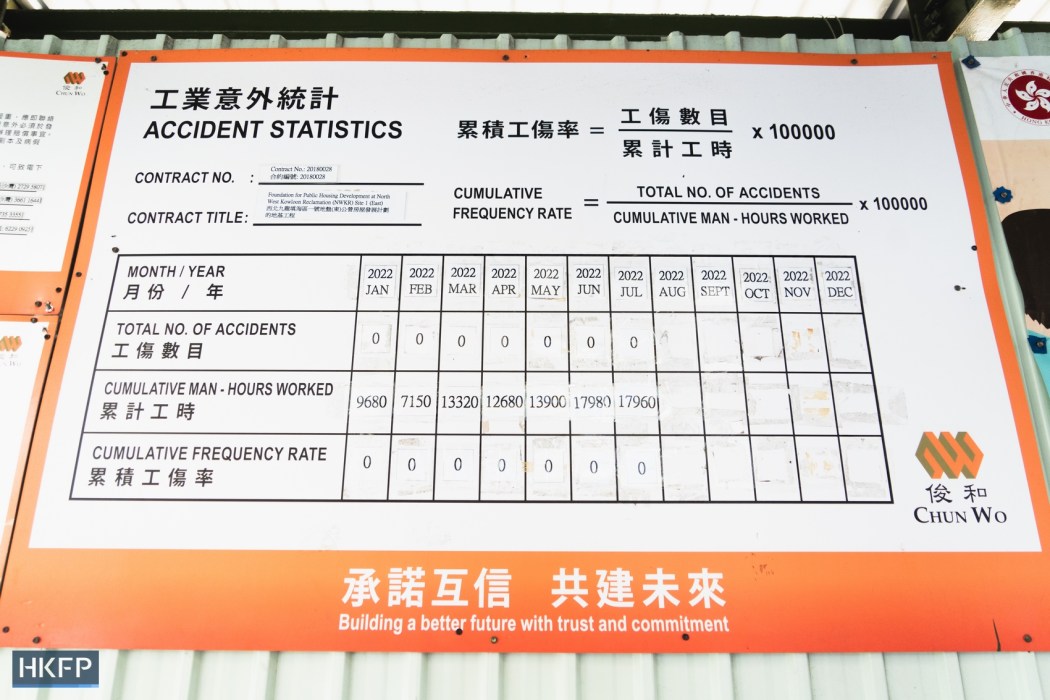

“Have you ever seen the accident statistics outside construction sites?” Ah Man asked. He said that many of the displayed statistics have been manipulated, as the developers have a higher chance of winning a bid when their accident numbers are low.

Ah Man told HKFP that many workers would settle compensation claims with their employers in private. ” I once knew a bar fixer who did not report his head injury at work, and he died in his sleep at home the next day. It is extremely difficult to claim for compensation in such cases.”

There were 18 fatal accidents and 2,532 industrial accidents in the construction industry in 2020, amounting to 26.1 injuries per a thousand construction workers, according to a document released by the Legislative Council’s panel on manpower.

Additionally, Ah Man said he has learned of construction sites where the very-hot-weather agreement has not been implemented. “We tried to do something about it, but no bar fixer is willing to come forward as they are afraid that their employers might settle a score later,” he said. “So we’ve got defendants, but no plaintiff.”

Chan, however, told HKFP that she was willing to step into the spotlight and play the role of “plaintiff” because she “had nothing to lose” as one of few women in the industry.

‘Women can’t handle the work’

Chan was raised in a bar fixing family. Her father ran a subcontracting business. Now 48, Chan first visited building sites as a child, and saw for herself the poor working conditions that bar benders endured.

“The bar benders didn’t have safety shoes, gloves, or helmets on. I recall once trying to assist with the work, and ended up crying over my scarred palms,” she said.

Because of these experiences, she did not immediately follow in her father’s footsteps. But then in 2007, Chan was living right next to the bar fixers’ strike. She befriended some of the senior bar benders, who told her that employers then had to provide helmets and safety belts.

“I thought it was no longer that bad, and the salary was higher than in other industries,” Chan said. She decided to enter the bar fixing industry, becoming one of Hong Kong’s first female bar benders.

However, finding permanent employment in the industry was challenging for Chan. She had an unstable income for nearly five years while working as a substitute for other bar benders.

“I’ve heard so many unsupportive things in the past: ‘women cannot handle the work’, ‘girls should stay at home’… But I’m stubborn. I’m a woman but so what? I could be on par with men as well,” Chan said.

She applied for a bar-fixing course, but heard nothing for almost a year. “The bar-fixing school claimed that they would typically call back in a month, but I waited and waited,” Chan said.

“After nearly a year, I phoned them to ask if they had neglected my application because of my gender. I told them I would file a complaint to the Equal Opportunities Commission.”

A day later, the college admitted her. Chan became a professional bar fixer in 2012.

Despite there being times when Chan was offered just over half the salary of her male counterparts, Chan has persevered. She has won industry awards, and, as a result of her repeated endeavours to address gender discrimination in the construction sector in the press, the issue of pay inequality has been largely resolved.

But there are still many issues that need addressing, she said.

For example, Chan’s employer of seven years did not pay severance or long service benefits when it fired her a month ago.

According to the Employment Ordinance, if an employee is in continuous employment – that is, employed by the same employer for four or more consecutive weeks for at least 18 hours each week – they are entitled to benefits such as holidays and severance.

However, the firm utilised a loophole in the ordinance to pay Chan’s salary using the names of different companies over the years.

Chan was furious. “Don’t day labourers deserve to get these benefits?” she asked. But demanding change and stricter regulations was challenging in Hong Kong today, Chan said, with Covid-related limits on public gatherings and other new rules.

“My husband asked me to back down as well. He told me ‘you’ve already achieved enough, now it’s someone else’s job’,” she said.

Fighting on

Both Chan and Ah Man said they believed they should continue their labour rights advocacy despite the recent political shift. Chan, who has been mocked by some colleagues for being popular in the press, explained she just wanted the best for her fellow bar benders.

“I’ll probably retire in my 50s… but even if I do not get the chance to enjoy such improvements, I’ve fought back. At least the next generation could enjoy them,” Chan, who has enjoyed the improvements made by bar fixers in her father’s generation, said.

As someone who has witnessed the ups and downs of Hong Kong’s labour rights history, Ah Man also told HKFP that he would continue to fight for the future.

“We need to adapt to the circumstances, instead of keep thinking how good it was in the past… we just have to do what we can at the moment, and prepare for a chance to come,” he said.

“We may not be able to fight for anything today, but maybe we can tomorrow,” the veteran unionist said, stroking his full white beard.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.