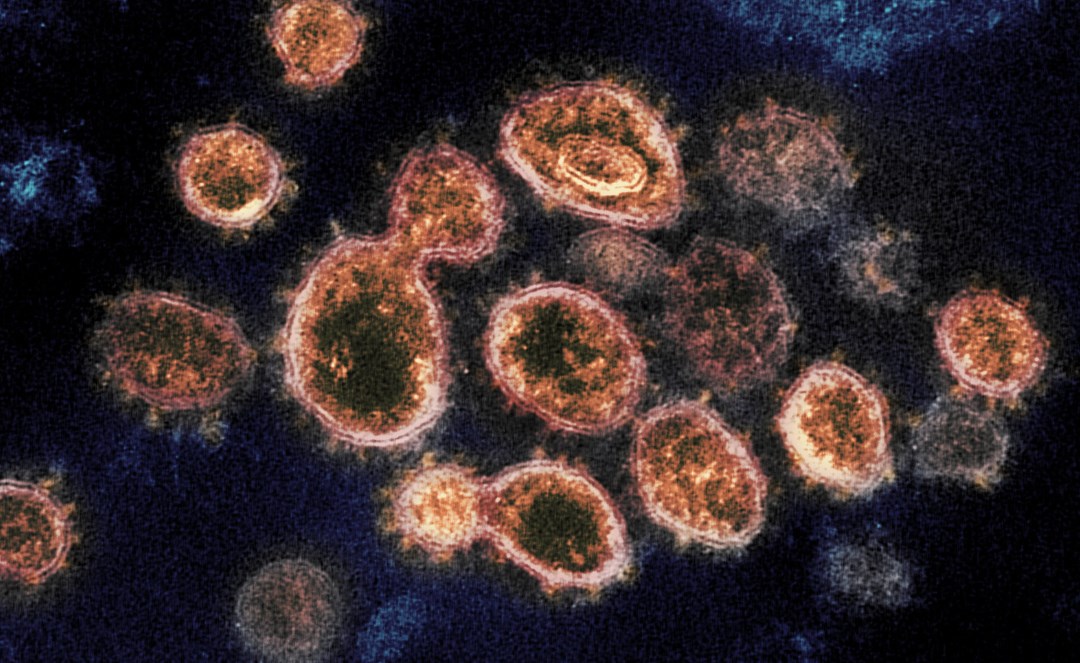

The Chinese government launched an infectious boomerang in late 2019 when it covered up a viral outbreak in Wuhan that turned out to be Covid-19. That boomerang has returned home with a mighty thwack, threatening to slow China’s economic rise while undermining its global reputation.

Two and a half years into the pandemic, Covid restrictions made it illegal to eat inside a restaurant in Beijing, seat of the Chinese Communist Party. In Shanghai, China’s premier commercial centre, tens of millions of people were not allowed to leave their homes. Many of them went hungry. Across China, hundreds of millions of people – more than the entire population of the United States – have been subject to severe Covid restrictions.

If leaders of the world’s democracies once looked upon China’s ability to lock down entire cities with envy, they may now be feeling degrees of schadenfreude as it experiences the kind of suffering that their countries endured. It is ironic that China’s propagandists have repeatedly pointed to those countries’ inadequate Covid policies to prove that China’s political system – which responded to the Covid-19 outbreak with reflexive coverups, distortions of the truth and outright lies – is superior to all others.

To be sure, blame for Covid-19’s casualties around the world can be spread widely. Many governments bungled their responses. But it’s hard to deny that much of the blame falls on Beijing. For two and a half years, Chinese officials have proactively exacerbated the pandemic. This reveals much about China’s authoritarian style of governance.

How has China responded to Covid?

China’s Covid-19 response has involved several overlapping and frequently self-reinforcing features, all of which have made the problem worse for the world. The government’s actions have ranged from arresting Chinese doctors and journalists reporting on the pandemic, censoring social media, spreading propaganda in news reporting, expelling foreign journalists attempting to learn what is going on, retaliating against local and global critics, and using diplomats to distort perceptions and refute criticism.

One of the initial features of China’s Covid-19 response was to cover up the outbreak. This may have been an attempt by local officials to avoid blame, but very quickly official denial went national. The government classified Covid-related research as politically sensitive, requiring researchers to get official permission before sharing what they knew. The National Health Commission silenced institutions with knowledge of the virus. The Covid-19 genome was mapped quickly by Chinese scientists, but they were ordered to keep silent. When they defied that order, their laboratory was closed.

The same day that China notified the World Health Organisation (WHO) of an unknown pneumonia spreading in Wuhan – after waiting several weeks to do so – online censors went to work erasing all internet references to the outbreak.

Whistle-blowers in China who attempted in late 2019 and early 2020 to make others aware of the dangerous new virus were subject to harassment, denunciation and arrest. The best-known example was Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang, who was forced by the Public Security Bureau to apologise for “false statements and disturbing public order” after he alerted his colleagues to the virus. When Li was killed by Covid-19, the government initially obstructed attempts to mourn his death.

The domestic Covid-19 strategy has changed little since the initial Wuhan outbreak, when severe restrictions were imposed on people’s movements. It seems to have worked quite well for earlier variants of the virus, although it’s impossible to know for certain about the number of Covid-19 infections and deaths in China due to the opacity of its official health statistics. The current Omicron variant has proved to be much more difficult to subdue.

Some international observers, not least in the WHO, initially parroted Beijing’s self-congratulation for the effectiveness of its strict controls on movement – even as Chinese officials decried foreign governments for closing their borders to travellers from China, just as it would subsequently do to theirs. Two and one-half years later, as Omicron spread widely throughout the country, China imposed its own restrictions on Chinese travellers, not to protect other countries from being infected by them but to prevent them from bringing Covid back to China.

The single most effective long-term strategy for coping with Covid-19 seems to be the universal use of effective vaccines. China’s approach to vaccines has been to pour scorn on foreign-made varieties while distributing and playing up the benefits of home-grown versions that are substantially less effective, especially compared to Western mRNA technologies, in preventing transmission, symptoms and deaths. Even 30 months into the pandemic, Beijing still refuses to authorise use of the most efficacious vaccines, apparently for purely political reasons.

Early in the pandemic, China used so-called “mask diplomacy” and “vaccine diplomacy,” the former offering personal protection equipment (PPE: medical masks, disposable gloves and the like) and the latter selling Chinese vaccines (almost universally at high prices compared to other countries’ jabs) to friendly countries, while withholding them from unfriendly ones. Many countries that purchased Chinese supplies came to regret their good fortune. Chinese PPE was often sub-standard, and Chinese vaccines failed to prevent local Covid epidemics.

Mask and vaccine diplomacy have been supplemented with a push to promote traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), a favoured project of President Xi Jinping, as treatment for Covid-19. When Hong Kong suffered a massive wave of Omicron, one of Beijing’s responses was to ship in huge quantities of TCM, despite its dubious efficacy. The local government in turn sent boxes of TCM to every household. If my elderly indigenous neighbour’s reaction is anything to go by, most of that TCM ended up in Hong Kong’s landfills: when I offered him my home’s consignment, he refused and pointed to the nearest rubbish bin.

China has been extremely prolific in its use of Covid-related propaganda and obfuscation (a.k.a. “fake news”). This has been manifested in ministry press briefings, diplomatic protests, Chinese official “news,” and social media, including Twitter and YouTube (both of which are banned in China). This campaign has sought to put a positive spin on China’s Covid response and refute, condemn and punish anyone who criticises that response. It has involved suggestions that the virus originated in other countries. For example, in March 2020, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman tweeted that the US Army might have brought the virus to Wuhan.

China has implemented a worldwide campaign to cover up its Covid-related failings. At the same time, officials and media have sought to highlight failures in other countries’ responses, for example pointing to high death rates, lack of care for the elderly, and inefficient vaccination campaigns. These are precisely the kinds of failures that have become evident within China in recent months.

The most common explanation for the origin of Covid-19 is that it spread to humans from animals, possibly from one of China’s wildlife farms, with a wet market in Wuhan seen as a likely conduit. But confirming this explanation is impossible because China has repeatedly frustrated investigations. A WHO fact-finding mission to China was delayed and constrained by the Chinese government. Due to pressure from China, the resulting WHO report on Covid’s origins was ambiguous. The Chinese flatly rejected efforts to investigate a hypothesis that Covid might have been inadvertently released from a virology laboratory in Wuhan.

Calls by other countries for credible investigations of the origins of Covid-19 have provoked fierce reactions from the Chinese government. Australia experienced this in 2020 when it called for an independent investigation. Despite support for the call from 137 countries in the World Health Assembly, China lashed out with crushing restrictions on Australian exports. This behaviour may have lasting worldwide repercussions. Failure to identify the original source of Covid-19 could very well make another pandemic more likely to occur, just as past cover-ups by China, for example the SARS outbreak in 2003, probably made this one more likely.

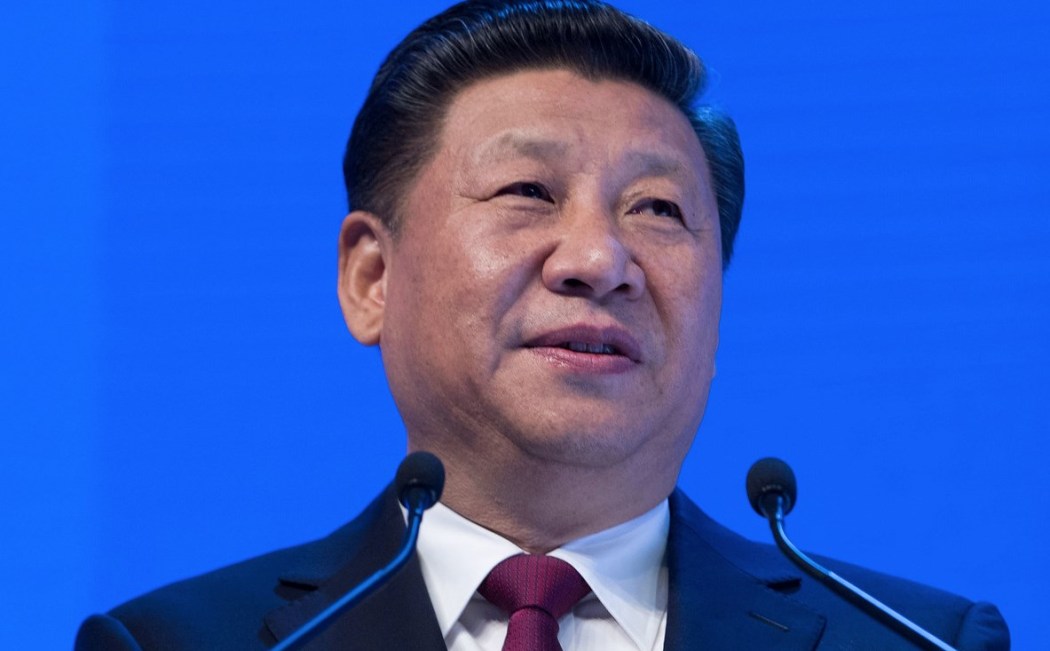

In recent months, China has doubled down on its so-called zero-Covid policy. One consequence has been an economic slowdown that not only affects China but is having knock-on effects around the world, contributing to global inflation. According to James Palmer, deputy editor of Foreign Policy, the zero-Covid policy is unlikely to change anytime soon due to the “political sensitivity for Chinese President Xi Jinping after two years of trumpeting the zero-COVID strategy as a personal achievement, as well as a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) success.” Xi seems unlikely to allow a relaxation because “he wants to use China’s success in containing the virus to prove that its top-down governance model is superior to that of liberal democracies.” Abandoning zero-Covid would require a radical reversal in state propaganda.

Another reason for the persistence of zero-Covid may be that China is in no position to let the Omicron variant careen through the population. A report published in Nature Medicine suggested that ending the zero-Covid policy would result in an overwhelmed healthcare system and 1.5 million deaths, largely due to the lack of effective vaccination coverage.

Some observers see China’s strict zero-Covid policy as a “Mao-style political campaign that is based on the will of one person, the country’s top leader, Xi Jinping – and that it could end up hurting everyone.” There are fears that the policy is the harbinger of a return to a planned economy. Lockdowns across China have resulted in marked falls in consumption and production. Even when the current outbreak is brought under control, the political obsession with maintaining the zero-Covid policy could cause the entire country to be “stuck in a costly cycle of outbreak and lockdown,” as Palmer put it.

While China’s propaganda has triumphantly proclaimed the continued success of the zero-Covid policy, people stuck in lockdowns are experiencing “rage, frustration and despair” that may be testing the perceived legitimacy of China’s leaders, at least if widespread expressions of discontent on social media, nightly banging of pots and other protests in Shanghai and other Chinese cities are any indication. Complaints on social media have become so frequent and fast that online censors have had trouble keeping up, enabling millions of people to see the failings of Covid governance.

Criticisms of the zero-Covid policy by Chinese experts have been censored domestically, although some have started to break through. International criticism is also growing. A week after President Xi doubled down on the zero-Covid policy, the director-general of the WHO described it as “unsustainable” given the infectiousness of Omicron, and WHO’s director of emergencies questioned the policy’s negative impacts on human rights and the economy. Predictably, their comments were condemned by Chinese officials and immediately censored.

It seems that zero Covid is evolving into a failed policy whose continuation is necessitated by other failed policies. China may be in this position due to officials’ stubborn unwillingness to learn from the West’s harsh experiences with Covid-19. Why learn from other countries when you think your own system of governance is eminently superior?

What does China’s Covid response tell us about its system of governance?

China’s response to Covid-19 reaffirms what was learned from the SARS outbreak in 2003: its system of governance is not effective in preventing deadly outbreaks of infectious disease, particularly those caused by zoonotic pathogens passed from animals to humans. Chinese officials are not inclined to reveal outbreaks. Doing so might imply that they have failed in their jobs. The knee-jerk political response is to cover things up, first from superiors, then from citizens, then from the wider world. As Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin argues, the Chinese government’s “defensiveness and overall lack of concern for things such as truth and transparency are part of its character.” The Covid-19 response simply reflects a wider pattern of governance.

Covid-19 also shows that China’s governance system is inclined to ignore science and foreign experience when they do not fit with the political objectives or preferences of party-state leaders. This has been manifested in the government’s failure to accept new Covid-19 epidemiology and technological innovation, for example by refusing to approve Western mRNA vaccines. The government relies on political diktats, such as the zero-Covid policy, despite protests from health experts. This inclination to believe one’s own propaganda, or at least to behave as though it is believed, has resulted in China repeating the failures for which it so vociferously attacked Western countries. For example, both Shanghai and Hong Kong failed to vaccinate enough of their elderly residents to avoid unnecessary casualties. At one point the latter city had the highest Covid death rate in the world.

Like other authoritarian regimes, China’s is fulsome in self-praise when things go well, and well-practiced in using propaganda and media manipulation to turn what might otherwise be bad news into good news. When things go especially well, or are perceived to do so, senior leaders are apt to hog the credit. When things go badly and redrafting reality becomes problematic, those same leaders avoid the limelight. After hailing his country’s response to Covid-19 in 2020 and 2021, President Xi has been notable for maintaining his distance from the setbacks of 2022.

China’s global Covid propaganda campaign is part of a larger initiative, stepped up markedly since the advent of Xi, to win respect for the country’s authoritarian style of governance and “cast the Party and its leadership in the best possible light” nationally and internationally. China’s propagandists also seem to be motivated by the political logic that has dominated Hong Kong in recent years: attributing all problems to mysterious external actors. This was demonstrated when Beijing blamed unnamed “foreign forces” for inciting people in Shanghai to protest at their treatment during Covid lockdown. In Hong Kong, one “patriotic” legislator suggested that those advocating a “live with Covid” alternative to zero-Covid policy could be in violation of the city’s National Security Law.

Covid-19 has shown that the Chinese government will lash out at anyone, or any country, that questions or pushes back against its official narrative. In China, everything is political, at least potentially. To challenge the leadership’s Covid policy would risk political suicide, so few officials are willing or able to propose alternative approaches. Indeed, questioning official Covid policy is considered disloyal and has been shown to lead to arrest. China’s opposition to allowing Taiwan to engage fully with the WHO’s pandemic response mechanisms, and its criticism of other countries for sending vaccines to Taiwan, shows that Covid is firstly a political concern for Beijing and only secondarily a concern about human life.

Another thing the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed is that China’s leaders can never resist an opportunity to use events to justify, at least from their own perspective, cracking down harder on what remains of personal liberties and freedoms. According to James Palmer, “The zero-COVID policy has been a boon to the security state, extending the range of tools and the normalization of surveillance.”

Ultimately, China’s response to Covid-19 seems to demonstrate that its governance system is not as effective and efficient as official accounts suggest. From letting the virus run riot around the world to being unable to vaccinate the elderly – or even to ensure that they are properly fed while in lockdown – China’s response has been far from exemplary. That may not prove that China’s political system is inferior to others. After all, many governments have dealt badly with Covid-19. However, surely China’s actions are evidence that its system is hardly a role model for other countries, possibly even those ruled by regimes that care little about human rights.

China’s Covid response affected its power and influence?

In recent years, China’s reputation and influence around the world have suffered from its progressively authoritarian policies at home and its increasingly aggressive behaviour abroad. Beijing’s denials of responsibility for the pandemic, alongside its obfuscations and vaccine missteps, have further undermined its international reputation. If its Covid-related propaganda was intended to improve its standing in the world, it has largely failed.

China undermined its standing quite early in the pandemic. Its coercive use of PPE in 2020 made other countries question its reliability as a source of vital supplies. Preconditions set by Beijing before selling its home-grown vaccines to other countries, such as requiring fealty to its foreign policy positions and excluding any country that has diplomatic relations with Taiwan, were hardly conducive to bolstering its global influence. It did not help that Beijing refused to be transparent about testing data related to its vaccines, and that it pretended nothing was amiss when its vaccines proved to be less efficacious than the Western ones that its propaganda machine sought to trash. Indeed, China’s style of vaccine diplomacy did not just fail; it was counterproductive, leaving China diminished in the eyes of much the world.

In Europe, China’s behaviour has garnered derision and increased scepticism of Beijing as an international partner. Several Chinese ambassadors in Europe openly criticised national responses to the pandemic and spread conspiracy theories about the origins of Covid-19. When China lashed out at Australia’s call for an independent investigation of Covid’s origins, Canberra was pushed more tightly into the geostrategic orbit of the United States. The worries of other countries observing China’s extreme reactions were understandably heightened.

Until recently Beijing could at least claim success in suppressing the virus within China. However, with widespread outbreaks of Omicron across the country in recent weeks, and the growing ramifications of the zero-Covid policy for the national economy, it can no longer do that with much credibility. From abroad, at least, the perception seems to be that China has bungled Covid-19. As columnist Bret Stephens asks, “Does anyone still think that China’s handling of the pandemic – its deceits, its mediocre vaccines, a zero-Covid policy that manifestly failed and now this cruel lockdown that has brought hunger and medicine shortages to its richest city – is a model to the rest of the world?” It appears that Covid-19 is cascading disaster for China’s global image.

A possible exception to China’s declining international reputation is in the world of autocratic regimes. China’s response to Covid-19 has served as a framework for them to use health concerns as justification for deepening censorship and repression. Joel Simon and Robert Mahoney argue that China’s response to Covid-19 “provided a playbook for information repression that spread around the world alongside the virus … facilitated by the narrative, created and spread by China, that authoritarian governments were better equipped to respond to the pandemic … because of their ability to control and manage information.”

But this advantage may be wearing thin even at home. Rigid enforcement of zero-Covid is undermining Chinese citizens’ and legal experts’ trust in the rule of law. There is worry that the government is drawing on its playbook from Xinjiang – strict surveillance of people’s behaviour and routinised restrictions on their movements – when implementing its zero-Covid policy. The norm in Xinjiang may become the norm across China.

The casualties of Covid-19

In the early months of the pandemic in 2020, official counts of cases in Wuhan and other cities were several thousand per day. Fast forward two-plus years, and the number of daily cases, based on China’s own reporting (which undercounts actual cases), reached tens of thousands per day. By the government’s own measure, two-plus years of “zero” Covid has resulted in infections that are at least ten times as prevalent as when the pandemic began. China seems to have been successful in keeping deaths from Covid low compared to several other countries. That said, we will never know how many people in China have died from Covid-19 or from all the Covid-related restrictions. It is likely that not even the government knows the true casualty figures. As most other countries return to normal while China implements more draconian restrictions, its Covid-19 response hardly seems worth trumpeting.

China will eventually join most of the world in “living with” Covid-19. That may happen after Xi has been inaugurated for his third term in office. One assumes that by then more vulnerable people will have been vaccinated. The government will surely take credit for things that go well and blame outsiders for things that continue to go badly. To be sure, the Chinese government is not unique in taking credit and rejecting blame; governments everywhere do that. But Chinese officials surely win the prize for brazenness (now that Donald Trump is out of office).

Internationally, the pandemic is knocking great chunks off the patina of China’s model of governance. Every casualty of Covid-19 is ultimately tied to decisions and actions taken by China’s leaders that failed to prevent and stop the initial outbreak in Wuhan. Around the world, about 15 million people have died due to the pandemic, with many more deaths certain to follow. Every one of those deaths could have been avoided if China’s political system were not reflexively tuned to hide, obfuscate, contradict, propagandise and deny truths and facts. The more people die from Covid-19, the more tainted the China model seems to be. China’s global reputation is dying the death of 15 million cuts – and counting.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.