By Francesca Chiu

For most of the pandemic, the number of cases in Hong Kong – and in elderly homes – was under control. But things have changed. With the current Omicron outbreak and the rapid increase of cases at elderly homes, the government has launched a series of policies to enhance the vaccination rate for the seniors.

The reason for the explosion in cases at care homes is simple. Government data shows the vaccination rate for elderly care home residents was around 25 per cent in February – a significant increase from 3 per cent in mid-2021, but still dangerously low for a group considered to be the most vulnerable to the pandemic.

As more news stories showed large groups of seniors being forced to wait outside of hospitals for testing or being sent to quarantine facilities, many commentators began asking the same question: “Why are elderly people not getting vaccinated”?

The short answer is that there are too many answers. Hong Kong’s seniors are not a homogeneous group that acts in unison. They do different things for different reasons. Based on my personal experience, I believe the question we need to ask is not “why, ” but “what”: what went wrong with Hong Kong’s approach to getting care home residents vaccinated?

Part of the answer is isolation. In mid-2020, before Covid vaccines became available, the government prohibited any outside visits to elderly homes during the third wave of infections. Said policy was relaxed in May 2021, allowing both vaccinated and unvaccinated family members to visit if they could show a negative test result. All this sounded good in theory. However, in practice, there were a lot of issues.

In the elderly home where my father stays, residents could have one visitor every week, and each visit could only last for 10 minutes. Just booking a visit was often impossible, since only eight people could each day. So out of the 260 residents at my father’s care home, only about one in five could see their family members in a given week, if they were lucky.

On the day of my first visit the problem was evident before I even stepped inside. There were leaflets about getting a jab plastered on the front door in a gesture to promote vaccination to visitors – inside was a different story.

Residents and staff were among the few priority groups that could register for a jab at the start of the vaccination drive, but there was a strong anti-vax atmosphere at my father’s elderly home.

During visits, staff talked about not getting a jab because they were worried about the side effects, but none had gone to a hospital or clinic for a check-up to ask about them. Given these staff were the closest regular contacts of many elderly home residents, what they said about vaccines mattered quite a lot.

While I appreciate the difficult work of staff at many elderly homes, my experience was frustrating. The anti-vax atmosphere there made it difficult to persuade my father to get a jab. Because of the restrictions on visits, family members have had limited opportunities to discuss the benefits of vaccines with elderly relatives. When the government banned all visits again in January of this year, it made personal communication virtually impossible once again.

My father finally agreed to get a jab and got his first dose this month after the government announced a new policy providing phone-in medical services for health assessment to residents.

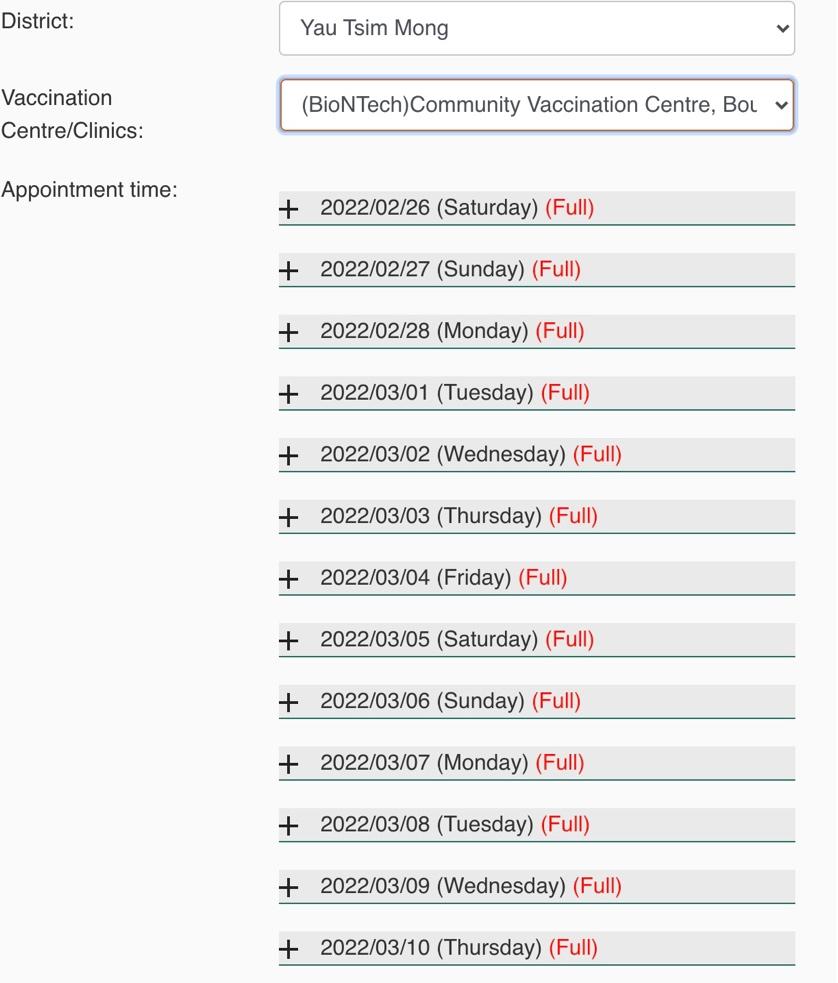

But there was another twist in this vaccination saga: his elderly home only provided Sinovac for residents in accordance with government policy, meaning anyone who wished to get the BioNTech vaccine had to book an appointment at a community centre on their own. That was a tough task, since many community centres providing the German-made jab were fully booked due to the citywide vaccine pass policy launched on February 24.

My father ended up waiting three weeks to get his first jab, and I, as his caregiver, spent weeks struggling to find a single rapid antigen test kit so I could prove I was Covid-negative and pick him up for the appointment.

As the family member of an elderly care home resident looking back at this Covid vaccination journey, it’s clear how many things went wrong at each stage in Hong Kong if our priority was to get the city’s vulnerable seniors vaccinated quickly.

To start, the government should have provided more support to care homes, such as doctor’s visits and health assessments, so individual residents’ health records could be checked for urgent need at the beginning of the vaccination programme. Sadly, the reality was just the opposite; many outpatient services were cancelled due to Covid-19, which made it difficult for seniors to get a health assessment.

More roll-out services for vaccination should be provided, and residents at every care home should be able to receive the BioNTech jab without having to try and book an appointment at whichever health centre can provide it at that moment.

Similarly, more support should have been provided to elderly home staff at the early stages of the vaccination programme. It would have been a straightforward matter to provide care home staff with free medical appointments to assess their health and answer their questions about side effects.

That would have made a huge difference in how the jab was perceived by both staff and residents from the start – simply requiring them to get at least one jab now to continue working at care homes, a new policy launched in January 2022, came far too late.

The government should also have required all visitors to be vaccinated rather than letting people provide a negative PCR test result, which sends a message to the public that testing is an acceptable and sustainable alternative to vaccination.

Finally, patience with elderly home residents is key. Many residents have cognitive issues and their understanding of what Covid is and what the vaccine does is limited. Many seniors have already been locked up in their elderly homes for more than two years and saw no obvious reason to get a jab – and from their perspective it was hard to disagree until the fifth wave hit.

Rather than locking the elderly up to protect them, the government should have provided incentives to encourage vaccination. Telling seniors the jab can protect them or will boost the economy does not work because they don’t care. Saying that getting the jab will not increase their death rate does not motivate them either.

But what if, after they got the jab, they could go outside more, or see the people they love more often, instead of being imprisoned in the same facility where they have been stuck for most of the last two years? That sort of incentive, at least, might stand a greater chance of convincing them than the prodding or punitive measures we’ve seen from the government so far.

Francesca Chiu is a PhD candidate focused on urban marginality and spatial politics in Myanmar at the University of East Anglia and the University of Copenhagen. She is a former researcher at the Centre for Civil Society and Governance at the University of Hong Kong. Follow her on Twitter.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.