Scientists say that a highly controversial deep-sea “gold rush” risks potentially devastating consequences for marine ecosystems, biodiversity, coastal communities and climate change.

The deep seabed is Earth’s final frontier but this mostly unexplored, dark and pristine abyss is threatened by highly destructive deep-sea mining which could be at full throttle within months.

“Most, if not all deep-sea biologists are very worried about deep-sea mining,” says Dr Moriaki Yasuhara a deep-sea ecologist and associate professor at the Swire Institute of Marine Science in the University of Hong Kong.

The deep-sea mining agenda is being led by nations like China and private corporations desperate to extract polymetallic nodules from the deep ocean floor. They say these potato-sized nuggets rich in valuable cobalt, nickel and other battery metals could be the key to the world’s sustainable future.

There is a growing chorus of dissent which insists the environmental impact of these deep-sea mining operations has not been properly assessed. They involve giant mechanical seabed tractors, hoovering up nodules before crushing them and trailing long plumes of sediment.

Yasuhara explains that the deep seabed can be compared to a tropical rain forest or a coral reef in terms of biodiversity but is unique because of its vast size and great depth. Until recently, this mostly pristine and precious environment has remained beyond the reach of mankind. The problem is that it is so technically challenging to reach these remote subsea habitats, several kilometres beneath the surface, that research is thin and information scarce.

“We simply don’t yet know how many deep-sea species exist,” says Yasuhara. The fear is that this environment will be devastated even before scientists can fully evaluate and understand it.

It is this lack of knowledge which prompted Yasuhara to join the 617 leading ocean scientists and policy experts from over 44 countries who signed a statement calling for a pause to deep-sea mining.

Marine Expert Statement Calling for a Pause to Deep-Sea Mining – click to view

The deep sea is home to a significant proportion of Earth’s biodiversity, with most species yet to be discovered. The richness and diversity of organisms in the deep sea supports ecosystem processes necessary for the Earth’s natural systems to function. The deep ocean also constitutes more than 90% of the biosphere, and plays a key role in climate regulation, fisheries production, and elemental cycling. It is an integral part of the culture and well-being of local communities and the seafloor forms part of the common heritage of humankind. However, deep-sea ecosystems are currently under stress from a number of anthropogenic stressors including climate change, bottom trawling and pollution. Deep-sea mining would add to these stressors, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning that would be irreversible on multi-generational timescales. Amongst the specific concerns over the impacts of deep-sea mining are:

- the direct loss of unique and ecologically important species and populations as a result of the degradation, destruction or elimination of seafloor habitat, many before they have been discovered and understood;

- the production of large, persistent sediment plumes that would affect seafloor and midwater species and ecosystems well beyond the actual mining sites;

- the interruption of important ecological processes connecting midwater and benthic ecosystems;

- the resuspension and release of sediment, metals and toxins into the water column, both from mining the seafloor and the discharge of mining wastewater from ships, detrimental to marine life including the potential for contamination of commercially important species of food fish such as tunas;

- noise pollution arising from industrial machine activity on the ocean floor and the transport of ore slurries in pipes to the sea surface, that could cause physiological and behavioral stress to marine mammals and other marine species;

- uncertain impacts on carbon sequestration dynamics and deep-ocean carbon storage.

There is a paucity of rigorous scientific information available concerning the biology, ecology and connectivity of deep-sea species and ecosystems, as well as the ecosystem services they provide. Without this information, the potential risks of deep-sea mining to deep-ocean biodiversity, ecosystems and functioning, as well as human well-being, cannot be fully understood. At the same time, a growing number of scientific reports (IPBES, IPCC, etc.) indicate that Earth’s biodiversity is increasingly at risk of extinction.

For the reasons outlined above, we strongly recommend that the transition to the exploitation of mineral resources be paused until sufficient and robust scientific information has been obtained to make informed decisions as to whether deep-sea mining can be authorized without significant damage to the marine environment and, if so, under what conditions. The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) provides an opportune period in which to collect more information about the species and ecosystems that could be affected by deep-sea mining. As scientists, we deeply value evidence-based decision making, especially in instances as consequential as a global decision to open up an entirely new frontier of the ocean to large-scale industrial resource exploitation. The sheer importance of the ocean to our planet and people, and the risk of large-scale and permanent loss of biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecosystem functions, necessitates a pause of all efforts to begin mining of the deep sea, in line with the precautionary principle, and an acceleration of research so that we can gain a better understanding of what is at stake.

The expert statement strongly recommends that “the transition to the exploitation of mineral resources be paused until sufficient and robust scientific information has been obtained to make informed decisions as to whether deep-sea mining can be authorized without significant damage to the marine environment and, if so, under what conditions.”

It’s not only scientists and experts like Yasuhara who are calling for a moratorium on all seabed mining activity.

Last December 1, Volkswagen Group, Triodos Bank, Scania, and Patagonia joined other major companies like the BMW Group, Volvo Group, Samsung SDI, Google and Philips in pledging to keep minerals sourced from the deep sea out of their products.

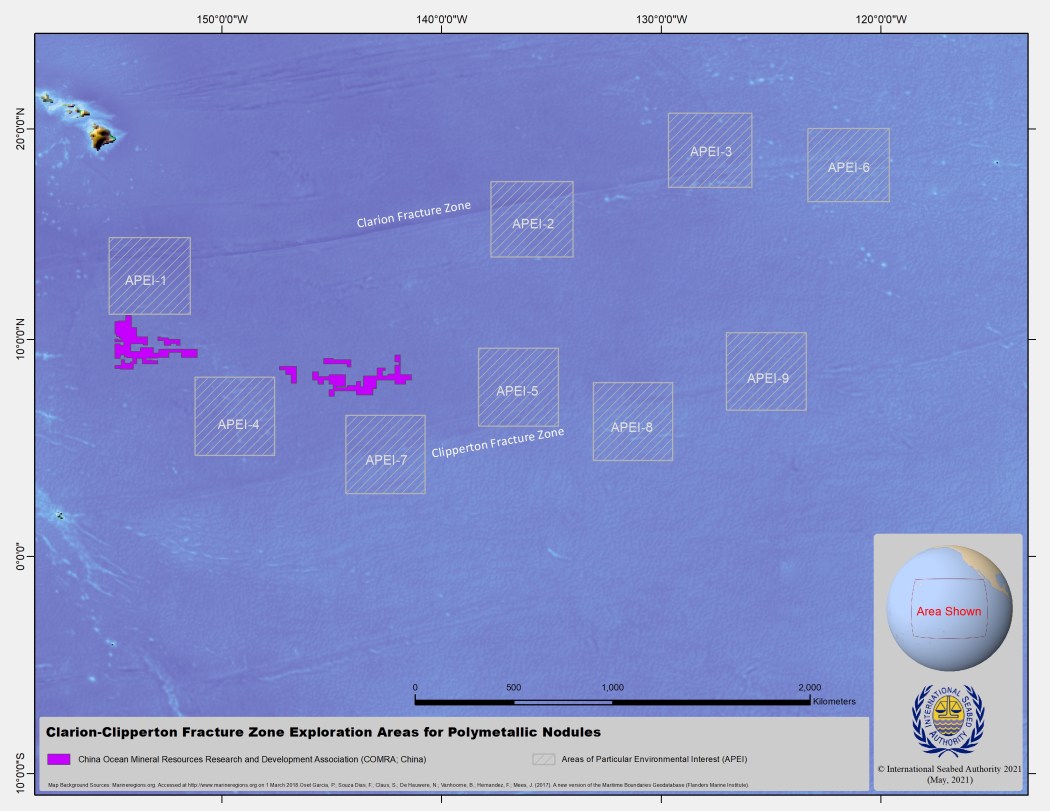

There is also much concern and opposition to seabed mining at grassroots level in the Pacific Island states like Tonga, the Marshall islands and the Cook Islands. Being adjacent to the area known as the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone where most of the deep-sea mining attention is focused, they have the most to lose from any future environmental destruction.

One of these vocal indigenous environmental concern groups, the Te Ipukarea Society in the Cook Islands, recently pointed out that the International Union for Conservation of Nature World Conservation Congress overwhelmingly supported a moratorium on seabed mining at its meeting in Marseilles this year.

While 44 government representatives from 39 countries backed the moratorium, eight representatives from six countries voted against it. This included two from each of Japan, Belgium and China. Of the 32 of more than 500 NGOs from around the world that voted against the moratorium, 26 were from China.

“We simply don’t yet know how many deep-sea species exist.”

Dr Moriaki Yasuhara

“These are the countries where a number of the companies wishing to mine the deep sea are based. It is for economic interest,” says Kelvin Passfield, technical director of the Te Ipukarea Society.

Of course, China is far from the only player looking to engage in deep sea mining but it is heavily committed to maintaining its market dominance in rare metals and rare earth elements. It has worked tirelessly to perfect its technology and has embedded itself deeply in the regulatory body for deep-sea mining, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) based in Jamaica.

The ISA has issued 30 contracts to state-backed companies, multinational corporations and start-ups to explore more than 1.3 million square kilometres of the seabed. China holds five contracts, more than any other country, that give it the right to explore and potentially exploit 238,000 square kilometres (an area more than six times the size of Taiwan).

While private corporations are keen to exploit short-term profits for shareholders, China’s approach is long-term, strategic and politically orchestrated. It is led by state-owned enterprises like the China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA) and China Minmetals Corporation, a giant international metals and mining enterprise based in Beijing.

China was one of the first nations to maintain a permanent representative to the ISA. Tian Qi is also his country’s ambassador to Jamaica and is often featured in local newspapers extolling the virtues of the ISA and his host country.

China was also the first country in the world to sponsor and maintain contracts for exploration for all three types of mineral resources in the international seabed area, outside the Exclusive Economic Zones of individual nation states. This makes China very popular with the ISA elite because the ISA derives its operating revenue from the licence fees reported to be US$500,000 each, plus a yearly administrative fee of US$47,000 per contractor. In this sense, China is the ISA’s most valuable client.

“From being the twelfth largest financial contributor to the budget of the Authority in 2000, China is now one of the top five contributors. This is remarkable progress,” said ISA secretary general Michael Lodge in 2018 at a contract-signing ceremony for COMRA. By 2016, China was the second largest contributor to the ISA and for China it’s a shrewd strategic investment with obvious geopolitical significance.

Polymetallic nodules and crusts are two of the most important mineral deposits in the ocean. They are rich in rare earth elements, iron, manganese, copper, cobalt, nickel, and other useful metals. According to a Wall Street Journal report in December, some estimates of China’s dominance of the rare-earth industry say it mines more than 70 per cent of the world’s rare earths and is responsible for 90 per cent of the complex processing. These rare minerals are used not only in the manufacture of battery components for electric cars and renewable energy but also for smartphone touch screens and missile-defence systems.

Not only does the ISA favour the interests of mining companies over the advice of scientists but its processes for [Environmental Impact Assessment) approvals are questionable”

Dr. Helen Rosenbaum

As if to underline the geopolitical significance of deep-sea mining to China, on December 3 as delegates prepared to travel to Jamaica for the first ISA meeting in two years, China approved the creation of one of the world’s largest rare-earths companies. China Rare Earth Group will aim to maintain the nation’s dominance in the global supply chain of the strategic metals as tensions deepen with the US.

“China is one of the most important countries with respect to the emerging seabed mining industry,” writes Richard Page, in his 2018 report on Chinese policy, activity and strategic interests relating to deep-sea mining in the Pacific region and published by the Deep Sea Mining Campaign.

Some think that China is too influential at the ISA. It’s a concern amplified by the fact that the US is one of the few nations not represented because it has not yet ratified the Law of the Sea Convention and so is ineligible for membership.

Critics claim the ISA is guilty of corporate capture and lacks transparency, independent scrutiny and scientific credibility.

“Not only does the ISA favour the interests of mining companies over the advice of scientists but its processes for EIA (environmental impact assessment) approvals are questionable”, says Dr. Helen Rosenbaum, coordinator of the deep-sea mining campaign.

In a recent press interview, Dr Sandor Mulsow who was head of the Office of Environmental Management and Mineral Resources at the ISA from 2013 to 2019, said he had witnessed “lots of irregularities.”

“The way ISA is working at the moment, it is not fit to regulate any activity in the oceans,” he told reporters.

The 26th session of the International Seabed Authority closed on December 14 after several days of in-person meetings in Kingston, Jamaica. Journalists were not allowed to attend and the ISA declined to respond to any media questions sent by email from HKFP on multiple occasions.

One key aim was to agree a roadmap for a new mining code to be in place by July 2023, which will regulate all extraction or exploitation activities. Reports indicate any agreement is still a long way off.

Unfortunately for the deep seabed and its rich biodiversity, the clock is ticking. On June 25 this year Nauru’s President Lionel Aingimea notified the ISA of the deep-sea mining plans to be carried out by a wholly owned subsidiary of the Canadian and NASDAQ-listed The Metals Co. He triggered a legal sanction to announce they would start mining in two years’ time (June 2023) if the key mining code of practice being developed by ISA was not in place by them. Critics say this will herald an unregulated wild west-style gold rush to ravage the deep seabed.

Despite a growing consensus that it is not necessary to trash the seabed in order to secure a sustainable future for humanity, and the widespread opposition from science and policy experts to rushing blindly into seabed mining, the clock is ticking down to July 2023.

Driven by multi-billion-dollar investments and China’s long-term geopolitical ambitions, and restrained only by a regulatory body lacking in any credibility, the prospects for the planet’s last unspoiled fringes seem bleak indeed.

For Yasuhara, given the unprecedented levels of ocean warming and the increased acidification of the sea, combined with ignorance of the destructive impact of deep-sea mining, this is the least appropriate moment to be embarking on large-scale destructive processes on an unknown and pristine environment. He emphasises that the deep ocean constitutes more than 90 per cent of the biosphere and plays a key role in climate regulation.

“This is not the right time from a climatic perspective to be starting man-made intervention in the deep-sea environment,” he says.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.