Let’s hope most Hongkongers have some personal triumphs to celebrate when the clock strikes midnight to ring in 2022. Because, let’s face it, the city as a whole does not have much to crow about over the past year.

It’s been, to borrow a phrase once famously employed by Hong Kong’s former monarch, an annus horribilis. Actually, let’s make that duo anni horribilis.

Hong Kong has been lurching and reeling for more than two years now: through the violent anti-government protests of 2019-2020, through the seemingly endless Covid-19 pandemic, through the decimation of personal freedoms wrought by the Beijing-imposed national security law, and through the calculated evisceration of any meaningful form of political opposition that has seen so many either flee the city or land in jail.

Hong Kong is a profoundly different city than the one we remember from two years ago — a city whose leaders have grown cold to the hopes and dreams of their own people in order to satisfy the authoritarian demands issuing, in ever-increasing number, from the north. A city which no longer aspires to the quest for democracy, sound governance and human rights. In too many respects, a lost city.

Considering all this, there’s not a lot of reasons to blow party horns and pull crackers.

Yet it cannot be denied that, despite all the alarming setbacks, there remains a spirit and verve about this place — perhaps much dampened and downtrodden but still very much alive — that the Chinese leadership and their local lackeys have been unable to squash and, let’s hope, never will.

We saw it in the Legislative Council election, the first under Beijing’s so-called “electoral reforms” mandating that only “patriots” (read: loyalists) were allowed to run. Some say that, thanks to the national security law, the days of mass protests in Hong Kong are over. But what was the LegCo vote if not a new form of mass protest? When 70 per cent of the electorate chooses to sit out an election, that’s a expression of discontent as large, if not larger, than any seen during the height of the anti-government protests two years ago.

That’s not indifference; that’s not apathy. That’s resistance. And it came after — indeed, was almost certainly at least partially prompted by — a highly public exhortation to Hongkongers from, among others, the mainland’s top official for Hong Kong and Macau affairs, Xia Baolong, to get out and vote for a more patriotic Hong Kong.

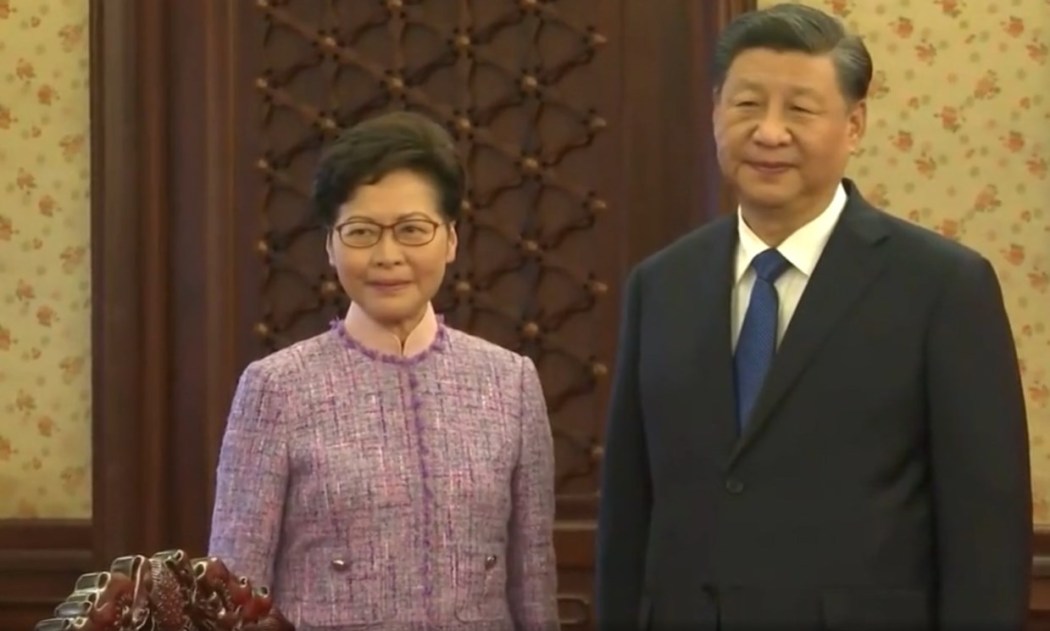

Laughably, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor tried to explain away the dismal turnout with a daft, less-is-more kind of logic: it only makes sense, the CE reasoned, that an electorate supremely satisfied with her government should express that contentment by, of course, feeling no need to vote.

But what else would you expect from the feckless Hong Kong leader who led us down this path of destruction?

The best Lam can do now is to pretend she has the support of the Hong Kong people whom she has so egregiously betrayed.

Of course, Lam is not entirely to blame for Hong Kong’s present sorry state of affairs. There have been plenty of bumps along the post-handover road under her three predecessors: Tung Chee-hwa, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen and Leung Chun-ying.

Until Lam’s arrival on the main stage, however, Hong Kong, despite its many challenges, was making reasonably good progress toward the civil society it aspired to be. For years following the 1997 handover from British to Chinese rule, the now seemingly all-powerful, all-meddling mainland liaison office made a point of honouring the spirit of the “one country, two systems” agreement by keeping a low profile and a hands-off approach to Hong Kong affairs.

Meanwhile, the legal protections for freedom of speech, assembly and the press in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, gave Hongkongers security about their basic rights in the immediate present. The Basic Law’s promise of gradual progress toward a democratic government also gave them hope for an even better future.

But under Lam’s leadership, that security was shattered and that hope dashed. Indeed, her stewardship has been so impaired — with the spectacular debacle of the ultimately failed extradition bill only serving as a particularly glaring symptom of her stunning political myopia in general — that Beijing shunted her aside and took over the city. She is now little more than a figurehead who does what she is told.

No matter what Lam says or does in her doomed attempts to recast the Hong Kong reality and reshape recent history in her favour, she will never have the support of the Hong Kong people, nor will any other puppet administrator whom Beijing puts in her place.

At this point, in the wake of the promulgation of the national security law, Hongkongers may not feel safe standing up to a government that has abdicated its responsibility to represent their interests and aspirations to the Chinese leadership. But they have also refused to lie down.

In such dreary New Year’s circumstances, that’s something to celebrate.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.