The demolition of Hong Kong’s democracy movement during the past year, along with the old way of electing local legislators, is by now a well-known story. Inevitably, the causes of this demolition have become the subject of contending narratives — between the central government in Beijing responsible for the demolition and those on the receiving end.

According to the official developing explanation of these events, there were no official broken promises. Hongkongers were led into their mistaken understandings of Beijing’s original intentions by London’s duplicitous manoeuvrings before Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule in 1997, and by Washington’s malicious meddling afterwards.

But those on the receiving end tell a different story and their experience continues to shape the course of events as Hongkongers — candidates and voters — prepare for their first Legislative Council election under the new rules, on December 19. With difficulty, a few remnants of pre-demolition days are trying to find their way in the new order.

The broken promises

As Hongkongers and many others saw it, the old way was supposed to have been a transition between the colonial system, and a new form of representative local government. It was to be based on the goal of universal suffrage elections for the Chief Executive and its entire representative assembly, known as the Legislative Council, or LegCo in local shorthand.

Beijing had promised all this and much more in preparation for the 1997 transfer from colonial back to Chinese rule and had even written the promises into a new Basic Law constitution promulgated by the central government for Hong Kong’s post-1997 use.

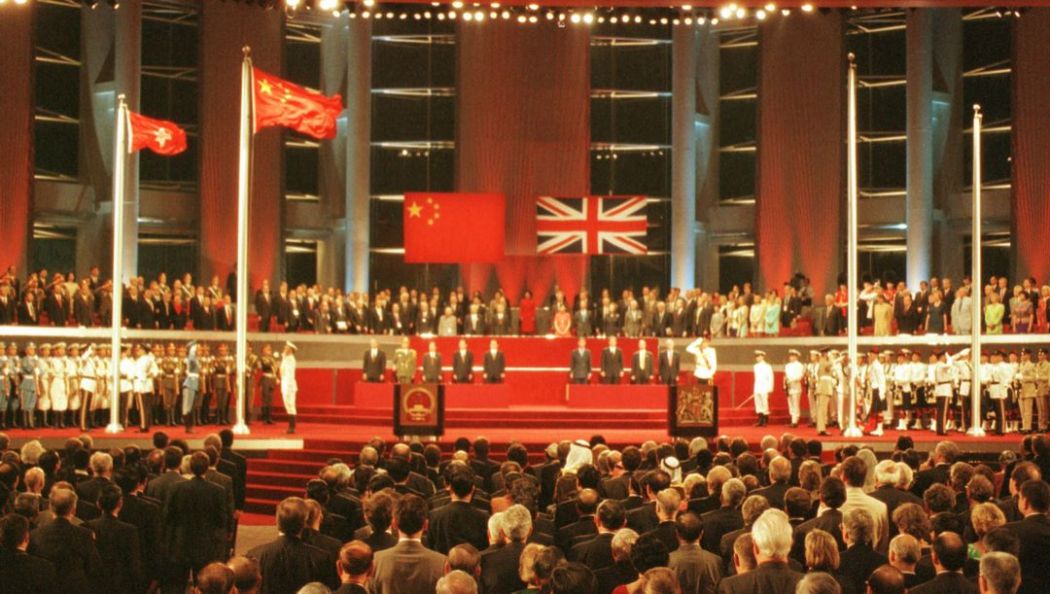

At the time, there was no end to haggling while the new post-1997 arrangements were being drafted, but in due course the day came and Hong Kong began its new life as a Special Administrative Region within the Chinese People’s Republic.

The population was already changed by the historic nature of the transition — from the safety of British rule to the uncertainty of life under China’s Communist Party-led government. Its revolutionary social transformation campaigns had sent several waves of migrants across the border into Hong Kong between 1949 and the late 1970s, so Hongkongers looked upon 1997 with some trepidation.

But the handover went smoothly enough and by then the transition from subjects to citizens was well underway. A participant community, confined to social concerns in colonial days, was beginning to think about its role and responsibilities in government and politics.

People were learning how to organise and campaign and many were looking forward to the challenge of trying to build something like a democratic form of local government in a city that had never known one before, and to do all that under Communist Party rule. It would have been a unique achievement.

But the organising and campaigning ultimately hit a dead end as Beijing embarked on a long-running procrastination exercise. It continued with one ill-defined delaying decision after another during the first two decades after 1997, as the promise of a government wholly elected by universal suffrage kept receding like a mirage on some distant horizon.

The only markers to guide the way were cryptic official references, such as those in 2014 and 2015, when Beijing began speaking in terms of its “universal jurisdiction” over Hong Kong, and of mainland-style universal suffrage elections for officially approved candidates.

This strange disconnect, between the demands of Hong Kong campaigners and Beijing’s resistance, continued until 2019, when patience snapped and the campaigning escalated into insurrection.

Although not announced at the time, Beijing’s response was finalised at the Fourth Plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee in late October 2019. It was just a month before Hong Kong transformed its insurrectionary mood into a dramatic landslide victory at the ballot box.

The occasion in Hong Kong was a local election for neighbourhood -level District Councils, insignificant in themselves but sending a clear message to Beijing officials that could no longer be deflected with their usual Aesopian rebuttals. Their candidates went down to defeat in a groundswell of voter preference for candidates who had united under a banner of support for the ongoing protests, and for “genuine” universal suffrage elections. This was despite the violence then at its height.

Turnout was 71 per cent of all registered voters, the highest ever recorded for a popular election since the custom was introduced here in the 1980s. Voters stood in line for hours, afraid that if they waited until later in the day their polling stations might run out of ballots.

Brave new world

Beijing’s October 2019 decisions took shape in the form of a National Security Law, promulgated on June 30, 2020, and revisions to Hong Kong’s Basic Law election regulations promulgated in March this year.

The new rules have been implemented with immediate effect and unaccustomed vigour. In place of the post-1997 system that democracy campaigners had been trying to build into some form of representative local government, a whole new way of political life is emerging.

As a net result of the new National Security Law, most of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy political leaders and activists have either fled overseas or been arrested and imprisoned for various political offences. Some have been granted bail. Most are in prison awaiting trial in a court system now overburdened by the volume of suspects.

Their offences derive both from the new law, and from the new draconian culture of law enforcement that has been introduced in its wake. The net result is a whole generation of potential candidates no longer eligible to contest elections as the search for dissident behaviour extends backwards and forwards across the June 30, 2020 National Security Law dividing line that heralded the new order. The new law is not retroactive but the search for dissident behaviour knows no bounds.

The election system itself has also undergone a dramatic reversal from what had originally been designed with an eye to the promised eventual goal of universal suffrage elections. That aim is no longer receding like a distant mirage but has evaporated altogether. In its place are a redesigned Legislative Council and the new electoral arrangements to produce it.

The new council has 90 seats, up from 70 before. But of the 90 seats, only 20 can be filled by voters on a direct one-person one-vote basis, as if to mock the Basic Law’s promise of a government wholly elected by universal suffrage. The new design features only two legislators directly elected by voters in each of ten newly-drawn Geographic Constituencies. Another 30 seats are reserved for the old “small-circle” occupation-based Functional Constituencies.

Additionally, 40 seats will be filled by an Election Committee that has itself just been formed by electors from the same functional constituency groupings set to elect the 30 legislative councillors. So the entire election now hinges on this convoluted circle of concurrent memberships, and the “safe” pro-establishment pro-Beijing individuals who are approved to hold them.

All candidates must be vetted by the new seven-member Candidate Eligibility Review Committee. Its vetting is done in consultation with Hong Kong’s new national security police unit that in turn works with the new mainland-staffed Office for Safeguarding National Security.

In colonial days, British officials spoke discreetly about appointing the right sort of colonists to the various local representative councils. Such appointments were regarded as being “safe.” Beijing’s designs are far more elaborate but the aim is identical: to try and guarantee that only the right sort of Hongkongers will occupy the spaces provided and perform the functions expected of them.

It could not be a more complete reversal of the old 1997 promises or a bigger defeat for the democracy movement they inspired. Yet officials keep saying they welcome one and all and want to see a diversity of candidates in the December 19 election.

Old-style pro-democracy partisans are free to try their luck — if any can be found capable of surviving the multi-layered search for incriminating evidence. Only those who do survive can qualify to meet the official prerequisite designation as a “patriot,” meaning someone who truly “loves China and Hong Kong” … the contemporary equivalent of “safe.”

The new ‘centrist’ candidate hopefuls

Yet inevitably, there are some who want to test the waters, who are not “pro-establishment,” or tried and true pro-Beijing “loyalists,” or pro-democracy partisans with politically blemished records.

These candidate hopefuls might be seen as representing the old moderate middle way that a few in Hong Kong’s democracy movement have long championed. Democratic Party founding member Anthony Cheung Bing-leung was among the first to declare himself in this respect. He quit the party in 2004 during mounting acrimony between its moderate and “Young Turk” members. He went on to join the administration of hardline patriot Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying.

Civic Party founding member Ronny Tong Ka-wah, originally a critic of national security legislation even in its Macau version as late as 2009, nevertheless felt himself at odds with the more determined activism of most other members. He left the party in 2015 and he, too, went on to join the governing establishment. He is now a member of Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s advisory Executive Council or cabinet.

Another such out-of-sync democrat was Tik Chi-yuen, a founding member of the Democratic Party who resigned also in 2015. Yet another was Nelson Wong Sing-chi, who also left the Democratic Party at the same time for the same reason.

Although the circumstances were a little different in each case, the last straw for all three men was mainstream democrats’ refusal to endorse Beijing’s 2014 mainland-style final non-negotiable plan for universal suffrage Chief Executive elections. It did feature universal suffrage, but for Beijing-approved candidates only. LegCo reform that was supposed to be ongoing had disappeared altogether from Beijing’s 2014 decision.

Yet if there is any chance of survival amid the ruins of Hong Kong’s pre-2020 democracy movement, it might come from these remaining variations on the original theme. For want of a better term, they are now being called “centrists.”

Several are now testing the waters and trying their luck under Hong Kong’s new election rules. According to preliminary calculations there are a dozen, including one such candidate in all but one of the 10 new Geographic Constituencies.

The two-week nomination period — from October 30 to November 12 — for the December 19 Legislative Council election has just ended. Aspiring candidates had to submit their nomination papers during those two weeks.

The paperwork had to include the signatures of 10 Election Committee members — two from each of the committee’s five sectors, including Sector Five that is wholly populated by unequivocal pro-Beijing loyalists. The vetting committee disqualified one candidate on Friday – Lau Tsz-chun, was running in the medical and health services functional constituency but was barred from the polls as he works for the government part-time, which is against election rules.

As to who is not there, the no-shows include members of the previously dominant Democratic Party, as well as the Civic Party, and “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung’s League of Social Democrats.

After much argument, and against the advice of veterans Emily Lau and Lee Wing-tat, the Democratic Party ultimately decided members could participate. But they also decided on the need for more proof of campaign team support in the various constituencies than the few aspiring hopefuls could provide. There were also indications of less than enthusiastic support from their voter base. Ultimately, no one came forward to contest.

The smaller Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (ADPL) went through the same sequence and emerged with the same result.

Most prominent among centrist “fallen-away” democrats testing the waters are Ronny Tong’s Path of Democracy and Tik Chi-yuen’s Third Side political group. They issued a joint statement published in the Chinese language Ming Pao daily on October 23, in which they introduced themselves as members of the “loyal opposition.”

According to their declaration, they affirm China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong and the need to respect national security. But they also affirm the original “one-country, two-systems” promises made by Beijing and seek to maintain Hong Kong’s existing way of life. This includes the search for a path toward universal suffrage elections. They also hope to improve the standards and accountability of Hong Kong governance.

Unfortunately, their ideals did not impress. Tong himself is not seeking to regain the LegCo seat he gave up in 2015. But two of his party members finally secured enough nominating signatures to qualify, down from his original plan for five. He also had to send out an S.O.S. appeal as the November 12 deadline for nomination applications approached.

Despite his own transformation from mainstream democrat to Executive Councillor, Election Committee members seemed reluctant to give his candidates the benefit of the doubt. The two hopefuls who ultimately passed the gate are Jeffrey Chan, a medical professional who will contest a Geographic Constituency seat in Kowloon East, and Allan Wong in New Territories Northeast.

Tik Chi-yuen barely won his Election Committee seat in its September election, making him the Committee’s sole non-establishment member. Both he and party mate Casper Wong secured the necessary signatures to enter the LegCo race in contests for a Functional Constituency and a Geographic Constituency, respectively.

Nelson Wong Sing-chi hopes to continue the fight for democracy and universal suffrage elections from a Geographic Constituency seat in New Territories Northeast. Also in the running is Mandy Tam, an accountant by profession and at one time a Civic Party member as well as a Legislative Councillor, holding the Functional Constituency accountancy seat.

And then there is that old-time political equivocator Frederick Fung Kin-kee, who never saw an election campaign he didn’t want to join. His old party, the ADPL, was eventually inherited by younger more activist members.

Fung parted ways with them in 2018, after behaving badly over candidate selection for a Legislative Council special election in his old Kowloon West constituency. But after vowing his election days were done, he has now decided to give it another try. Fung says he has learned his lesson and his new vow is to “never say never again.”

The new ‘campaign managers’

Still, there is one thing to note about any election that includes any kind of a popular vote no matter how constrained. They somehow always manage to contain elements of humor, like the irrepressible Frederick Fung who just can’t resist another run on the campaign trail.

But in this case, the spotlight falls on the least likely of performers: Beijing officials working in its representative Liaison Office here. For the first time in their well-disciplined lives, they have had to learn what it’s like to put together an election campaign.

As has been widely reported, officials are concerned about the appearance of a walkover stage-managed election. And rightly so. With all of Hong Kong’s most popular politicians not in the race — and with intimations of a blank-ballot protest vote on the part of the general public — the December 19 LegCo election might well look like what it is, namely, an election for patriots only.

Always politically correct, the South China Morning Post nevertheless told the story. According to an October 30 headline, “Beijing ‘micromanaging’ Hong Kong Legco election, down to checking, approving candidates behind the scenes, sources say.”

Sighs of relief were almost audible in the follow-up front-page edition on November 13, the day after nominations closed: “Legco Election Will Be First to See Every Seat Contested.” This account repeated an anecdote reported earlier about pro-establishment incumbents standing for re-election in previously uncontested seats who were told to go out and find someone to run against this time.

As for those who cannot lose, the Post has done an even better job of introducing the new line-up that together with the old guard should make December 19 a perfectly safe Election Day. The experienced veterans are, of course, the Federation of Trade Unions (FTU), with a history dating back to the late 1940s, plus the political party, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB).

Both have long experience in fielding candidates but are now being scrutinised more carefully by the new mainland managers. The old guard is being criticised for not having produced any outstanding political talents. Among their politicians, only DAB founding chairman Jasper Tsang Yok-sing, now retired, has wider political appeal.

The reason, of course, is that Tsang is willing to do what the others including their new in-house critics are not, namely, acknowledge wider public concerns beyond those of the pro-Beijing community. The managers have much to learn.

Newcomers recruited into the mix are being introduced as “elites” … business executives and others working in cross-border enterprises, the very same who made their entrance a few weeks ago in the Election Committee election. These are seen as being especially important for promoting Hong Kong’s role as an economic city and financial centre, in accordance with Beijing’s longstanding vision for its ex-colonial territory.

Still, there is one candidate hopeful who doesn’t fit easily into either of the two — centrist or pro-Beijing loyalist — categories. He is Gary Zhang Xin-yu, a railway engineer by profession, who happened to be the man in charge at the Prince Edward Mass Transit Railway Station on the night of August 31, 2019.

The day marked the anniversary of Beijing’s August 31, 2014 decision on universal suffrage Chief Executive elections and huge crowds had gathered downtown, across the harbour on Hong Kong Island. The MTR incident occurred that night as people were heading home, back uptown, with police in search of angry protesters jumping turnstiles and smashing ticket machines.

Police ordered the station closed and left behind the aftermath of a bloody scene that no one had been able to witness, giving rise to unfounded rumours that persisted for months. The main entrance to the station became a place of pilgrimage where people left flowers and messages in memory of those thought to have been killed in the 8.31 Incident.

Zhang’s family had migrated to Hong Kong when he was a teenager. Having grown up and been educated here, he says he now regards himself as a local. In a recent interview, he told how he spent months afterwards trying to explain to people that at least no one was beaten to death on that night. But he had also called for an independent investigation into the issue of police brutality, which officials and police have adamantly resisted since the protests began in mid-2019.

Zhang belongs to a political group called New Hong Kong Prospect, recently organised by mainland migrants like his family. He plans to run for a Geographic Constituency seat in New Territories North near the border, home to many new mainland migrants.

Candidates running in the Kowloon East district are Tang Ka-piu, Ngan Man-yu, Jeffrey Chan, Wu Kin-wa, and Li Ka-yan. Candidates running in the Kowloon West district are Vincent Cheng, Leung Man-kwong and Frederick Fung. Candidates running in the Kowloon Central district are Starry Lee, Mandy Tam and Yang Wing-kit. Candidates running in the New Territories Northeast are Chan Hak-yan, Dominic Lee, Allan Wong and Nelson Wong. Candidates running in the New Territories North are Lau Kwok-fan, Shum Ho-kit, Gary Zhang, and Judy Tzeng.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.