Before he first left Hong Kong for Taiwan in 2016, former research assistant professor Frank Wong began learning Taiwanese. His reasoning was straightforward: he believed most people in Taiwan conversed in that language.

“I thought it was logical that most Taiwanese people would be able to speak the Taiwanese language… I thought Mandarin was the official language on formal documents, but in daily life, most of the time they would speak the Taiwanese language,” he told HKFP from his office in Taipei.

The Hongkonger soon realised he was mistaken. “When you go to the streets, not many people will talk if you speak in the Taiwanese language.”

The rare usage of Taiwanese, particularly on the streets of its capital Taipei, is a legacy of decades of colonial rule. During 50 years under Japanese rule, and the Kuomintang’s subsequent martial law from 1949 to 1987, generations of Taiwanese were banned from speaking their mother tongue in public.

“A whole generation’s learning in this language was washed away, and with this language a culture and identity was also washed away,” said Lí Sì–goe̍h, a Taiwanese language advocate.

Before the arrival of the Kuomintang, Taiwanese – a language from China’s Fujian province also referred to as Taigí, Taiwanese Hokkien, Hoklo or Southern Min – was spoken by most Han immigrants who arrived on the island from the 17th century onwards. Other languages, including other Chinese languages such as Hakka and dozens of different Austronesian indigenous languages, were also spoken on the island, a reflection of the diversity of ethnic groups that have lived on the island for centuries.

Today on the streets of Taipei, Mandarin – the language imposed on the island by the Kuomintang – reigns as the lingua franca.

A stigmatised tongue

Wong’s initial false assumption, however, did not stop him from continuing to study Taiwanese – something of an uphill battle, following the decades of oppression which sought to erase the use of Taiwanese in public life.

“Nowadays, most Taiwanese can’t see the usefulness and importance of the Taiwanese language, and they believe that being able to speak Mandarin will be enough,” he said.

The academic’s attempts to use Taiwanese in his daily life have been polarising. Although some Taiwanese have hailed his efforts to engage with a long-oppressed facet of Taiwanese life, some have also taken offence at his use of the language in professional settings.

“Some Taiwanese stigmatised the language and believe that it should not be used in formal situations,” he told HKFP. “I had an experience in southern Taiwan where a Taiwanese said to me angrily, ‘How can you speak the Taiwanese language in such a formal situation? I am very surprised that the university employed this kind of faculty member!'”

This anger speaks to the threats facing the Taiwanese language in the island today, where its use is almost confined to certain social milieus.

“You often hear construction workers or police officers speaking Taiwanese… so there’s always been these environments [to speak it], even though it’s been formally suppressed,” Catherine Chou, a Taiwanese-American history professor, told HKFP.

“That’s the tricky thing when a language becomes very context-specific, there’s the danger of actually losing it, because the mentality becomes ‘It’s not for general use, it’s for the home, it’s for very specific business relationships, it’s for people that I know, it’s not for people I don’t know’,” she continued.

Although census figures show Taiwanese is spoken by around 80 per cent of the island’s inhabitants, most younger Taiwanese, particularly in the capital, use Mandarin in public and among themselves.

“In Taiwanese society, there’s an unconsciousness of language loss, people see it as a natural process. They see it as natural that now we speak Mandarin, but people don’t really think about how that happened,” Joshua Yang, a Taiwanese computational linguist who specialises in the role of technology in language preservation, told HKFP.

Promoting Taiwanese

The fear of losing the language has prompted a push to revive use of Taiwanese in everyday life, a mission some Hongkongers now living on the island have also made their own.

Wong, 43, now teaches business information systems at the National Taiwan Normal University, where he incorporates Taiwanese in his courses as much as he can, posting bilingual announcements on social media and inviting Taiwanese guest speakers. Because of this initiative, some of his students have begun to learn Taiwanese.

Recently, he has also enrolled in a PhD course in Taiwanese Literature at the National Cheng Kung University. He is determined to teach future classes solely in Taiwanese.

“From a Hongkonger’s perspective, I believe that speaking the Taiwanese language can give Taiwanese an impression that we don’t consider Taiwan as a lifeboat,” he told HKFP. “By using the Taiwanese language, we can demonstrate our determination to build our new home with the local Taiwanese.”

Wong’s not the only Hongkonger who feels this way.

Lí, the Taiwanese language advocate, moved from Hong Kong to the southern city of Kaohsiung with her Taiwanese husband Ngô͘ Hê-bí five years ago. She initially asked her husband to teach her Taiwanese to communicate with her elderly in-laws. The two quickly realised that they both needed to take formal lessons, when Ngô͘, who could communicate in Taiwanese, struggled to teach Lí the basics of the language.

The 37-year-old told HKFP she soon found that many Taiwanese friends were blind to the limits of their knowledge of their ancestral tongue, because they lacked everyday opportunities to converse in it.

“It’s not like they don’t know the language at all, most can understand it and can say simple phrases. But if you want them to try and speak only in Taiwanese for three whole minutes, many of them couldn’t do it.”‘

The discovery prompted the couple to promote the use of the language in a quintessentially Taiwanese fashion — by creating a mascot, the Taiyu Mao or Taiwanese Cat, to prompt Taiwanese speakers to use the native tongue.

Lí first created a series of Taiwanese Cat stickers for Line, a popular messaging app, to trigger curiosity. “If we don’t use it in their daily lives, that’s how language dies out. So it was important to promote this language,” she said. “You can’t completely express Taiwanese culture with Mandarin – something is bound to be lost in translation.”

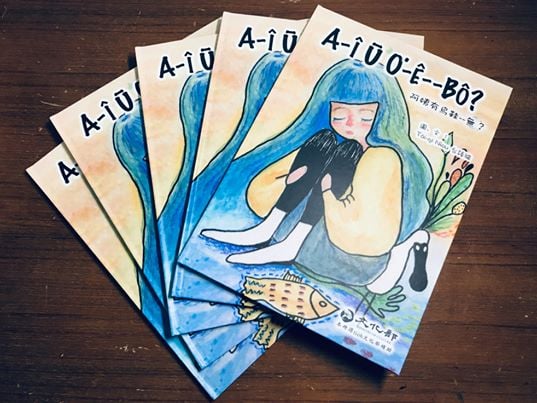

The couple now also sell merchandise to promote the cause, including an illustrated book to teach the Taiwanese tones to children, funded by a grant from the Ministry of Culture. Their most popular product is a T-shirt which says Kong Taigí, or “Speak Taiwanese”.

The two have also arranged Taiwanese exhibitions to raise awareness. “Taiwanese is not a language that many people will take the initiative to learn, like Japanese or Korean, so we want to promote the language among people who may not normally have contact with it.”

The popularity of Taiwanese Cat merchandise is spreading. Earlier this year, the couple licensed the cartoon to a face mask producer. In some bookstores in Taipei, booksellers give customers free face masks with the Taiwanese Cat. “Practise speaking Taiwanese with me,” one design reads.

It has also become an unofficial icon for the wider cultural push to revitalise the language. Taiwanese-language rapper GLOJ wears their T-shirts in a music video released early this year.

National languages

Although it has received government support, the reviving of the language has drawn some controversy.

In early 2019, Taiwan’s government passed the Development of National Languages Act, which guarantees that 18 ancestral languages be treated equally and that schools provide opportunities for children to learn the national languages. It also guarantees that any national language can be used in the city’s legislature, courts and government with the help of simultaneous translation.

But the implementation of 18 national languages in official settings has not gone smoothly. In late September, a conversation between Defense Minister Chiu Kuo-cheng and the progressive Taiwan Statebuilding Party’s only elected lawmaker, Chen Po-wei, became heated after Chen requested the use of an interpreter so he could speak in Taigí, his mother tongue.

“I can’t believe there’s even a controversy. People are supposed to be able to use these now-national languages in these public venues,” Yang, the computational linguist, told HKFP. “Even if it’s a statement, it is incredibly valuable to raise awareness for people to see that these are real, actual, proper languages that can be used in all different circumstances, that not only Mandarin has this power.”

The notion that Taiwanese is reserved for informal settings is an unnatural one for members of the island’s diaspora who grew up in a Taiwanese-speaking environment abroad. “I grew up with sermons in Taiwanese. I always had this knowledge that you could discuss anything in Taiwanese, that it was all possible,” Chou told HKFP.

Reclaiming roots

For Yang, the push to revive Taiwanese is deeply personal. Growing up between Australia and Taiwan and learning the language from his grandmother, he has witnessed the gulf that the displacement of Taiwanese by Mandarin has created within his own family.

His Taiwanese cousins, who were raised in Taipei, cannot meaningfully communicate with their grandmother, who moved to Taipei in the 1950s and cannot speak Mandarin.

“In my generation, most of them don’t really speak Taiwanese. It creates an obstacle for them to be able to actually communicate with my grandma… I can just see that my grandma is being left out of the family conversation. She would just be sitting there not understanding what we say, and I feel terrible for her.”

The loss of language is the loss of heritage, he said. Being able to communicate with his grandmother means he is not only able to have enjoy a richer connection with her, he can also inherit his family history.

“I get to learn about her stories, her dreams when she was young, her upbringing and learn about what happened in her generation,” he told HKFP. “So language is really our connection with the past… being able to speak Taiwanese means that I am able to understand the past of Taiwan better.”

“Language is the soul of the culture and it’s a continuation of your heritage. It’s certainly unfair for these language minorities to lose the opportunities to connect with their own past because of the power structure of language dominance in this society,” he added.

The push for more language diversity in Taiwan is also a way to assert a Taiwanese identity separate to that imposed by the Chinese nationalist legacy of the Kuomintang, and Beijing’s narrative that the island is a renegade Chinese province awaiting unification with the mainland.

For Lí and Ngô, the couple behind the Taiwanese Cat, the urgency of preserving the Taiwanese language is essential to the assertion of a Taiwanese identity. “When we are abroad, people would ask us ‘If you’re from Taiwan, why do you speak Mandarin?'” Lí told HKFP.

“Speaking these other languages [besides Mandarin]… give Taiwan connections to other parts of the world,” said Chou, the Taiwanese-American professor.

“Taiwan can’t afford to be monolingual again, because then what the world is like inevitably will be shaped by what the PRC puts out as this dominant Mandarin language market. So if you want to develop a different consciousness, language is a really essential part of that,” she said, referring to the People’s Republic of China.

Beijing views Taiwan as a renegade province which it has vowed to “unite” with the mainland by whatever means necessary. Surveys in Taiwan, however, show an overwhelming majority have no desire to become a part of the PRC.

“If Taiwanese people only speak Mandarin, their idea of what the region is, their idea of what the globe is, even against their will, will be tied to the PRC, so you have to be multilingual in this era,” Chou said.

Efforts to revitalise Taiwanese in every sphere of life, both backed by grassroots efforts and recent government policies, still have a far way to go, advocates say.

“People need to start to think about using these languages in all different daily usage… Have people thought about writing in Taiwanese on a 7/11 sign? All kinds of possibilities are worth thinking about to retake that language space that has been taken away,” Yang said.

The movement to revive the language is not limited to those seeking a way to reconnect with one’s roots, it’s also a way to plant new ones.

Wong, the professor from Hong Kong, told HKFP his determination to use the Taiwanese language has helped him find community and purpose in his new home. “If I haven’t got as many Taiwanese language advocates as my friends, I think I may not choose to stay in Taiwan,” he said.

“I am happy to have them as my friends because we all work together to save the language.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.