The COP26 climate summit in Glasgow will be a make-or-break event for efforts to limit global warming to 1.5°C. If the world’s most-polluting countries don’t greatly strengthen their promises to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move rapidly to implement them, the climate crisis will become a climate catastrophe.

China is the largest national source of the greenhouse gas pollution that is causing climate change, accounting for more than a quarter of the global total and surpassing that of the developed world. Adding insult to injury, China’s emissions are still increasing. Success at Glasgow will be impossible without an immediate reversal of this trend, followed by action to reduce China’s emissions rapidly.

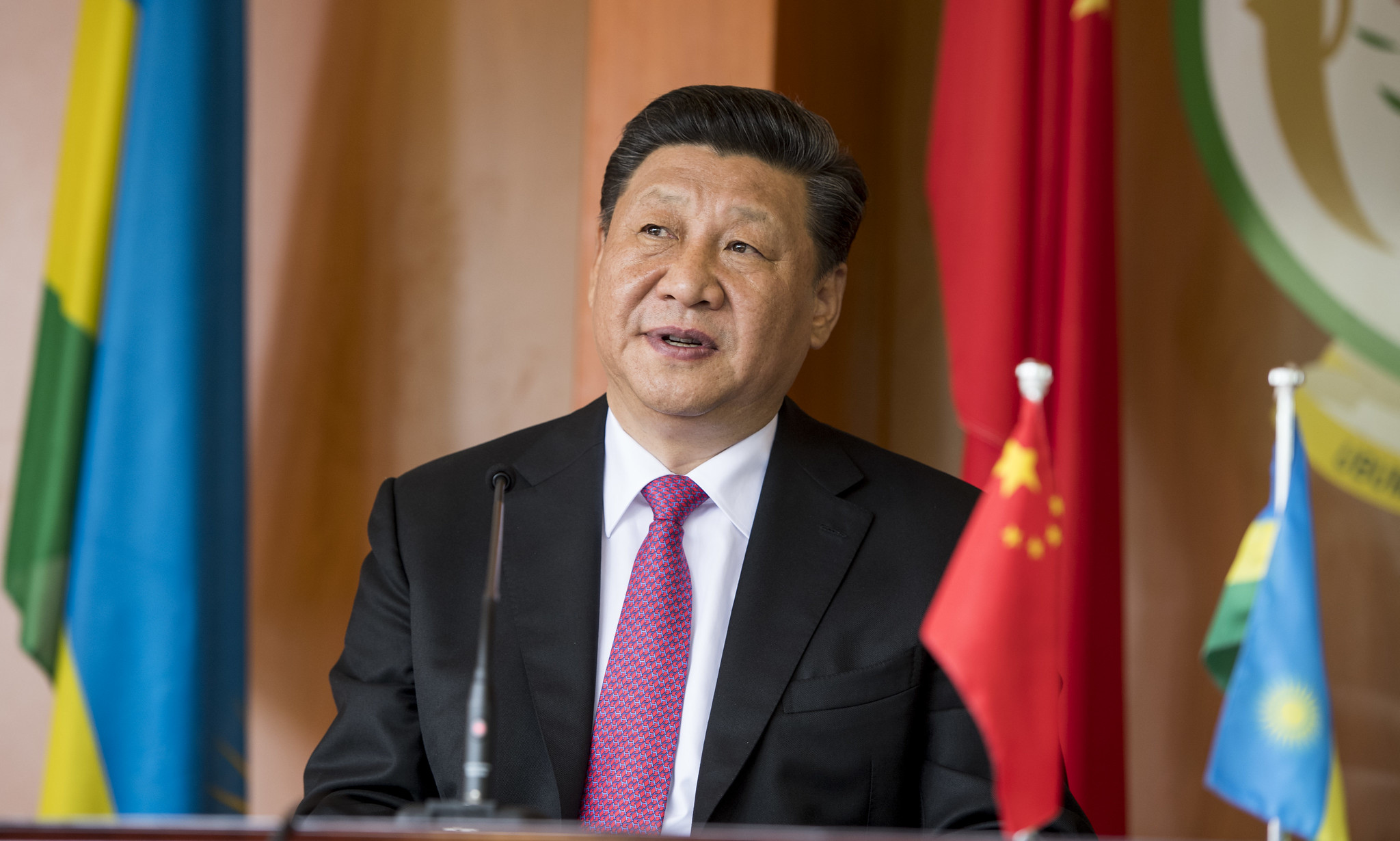

Up to now, China’s pledges and actions have not squared with its outsized role in the climate crisis. President Xi Jinping has pledged that its emissions will level off no later than 2030, but this is a recipe for climate disaster given the need to cut global emissions very substantially this decade.

Xi recently promised that China would stop building coal-fired power plants abroad, even though they feature prominently in his much-heralded Belt and Road Initiative. Yet many new coal plants are now under construction within China itself. Instead of closing coal mines, China is reviving many of those that were previously decommissioned.

President Xi has also pledged that China will become carbon-neutral by 2060. That’s a decade beyond what scientists and the United Nations secretary general say is necessary globally to avoid the worst effects of climate change. What’s more, Xi’s pledge rings hollow without a concrete action plan to reverse emissions immediately and reduce them quickly. Accordingly, Climate Action Tracker has described China’s emissions pledges as “highly insufficient” for meeting the targets of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

What explains China’s reticence to reduce its climate pollution? The primary answer is conspicuous: like most other countries, it puts its economy first. Despite world-beating efforts to roll out climate-friendly forms of energy, notably wind and solar, more than four-fifths of China’s energy still comes from the burning of coal and other fossil fuels. Reducing that percentage while honouring the Chinese Communist Party’s promises to improve livelihoods and continue a rapid technological and military buildup is no easy task.

But there’s another reason that China has been reticent to end its addiction to fossil fuels: Chinese officials blame developed countries, the United States in particular, for the climate crisis. They repeatedly emphasise that the developed countries produced most of the greenhouse gas pollution that is driving global warming and the many adverse impacts of climate change.

Beijing officials argue that the developed countries should “shoulder the responsibility” for climate change, “take the lead” in cutting emissions and provide more aid to developing countries. Because developed countries got rich by burning fossil fuels, officials even argue that China still “enjoys the right to receive funds” from them – despite China vying with the United States to be the world’s largest international aid donor.

While China now pollutes to a greater degree than the developed countries, their combined CO2 emissions since the mid-18th century are four times those of China. A conclusion that Chinese officials might reasonably draw is that their country’s contribution to climate change is relatively small in historical terms. But there are several weaknesses in such logic.

For example, official measures of historical greenhouse gas emissions begin with the Industrial Revolution, when the burning of coal started to take off in the West. Those measures rarely consider emissions before the mid-19th century. Consequently, they fail to account for China’s emissions throughout the vast majority of its history.

Chinese officials would no doubt argue that China was once the world’s greatest power, a centre of advanced civilisation and a source of innovation and wisdom for millennia. They would be less likely to point out that the country experienced massive deforestation during much of that period, resulting in carbon emissions and the decimation of a gargantuan natural repository for carbon (trees absorb carbon dioxide into their tissues and deposit it into surrounding soil). Reforestation has begun only quite recently in China. Other land-use practices, such as rice cultivation, have for centuries produced prodigious greenhouse gas emissions.

To be sure, China’s ancient emissions each year were vastly lower than they are today, but they occurred over thousands of years. The centuries-long warming potential of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, combined with many centuries of greatly diminished forest carbon sinks, means that China’s historical emissions are far from inconsequential for climate change. Nevertheless, those emissions are not considered when diplomats apportion blame for the climate crisis.

Arguably it is arbitrary to start measuring any country’s impact on Earth’s climate from the Industrial Revolution. Why not start at, say, the middle of the 17th century when the modern international system was ostensibly codified, or 1492, arguably the time that globalisation began, or perhaps 1000 or the year 0 (the start of the Common Era), or maybe around 3000 BCE, when human civilization took shape? Why not start when Chinese civilisation originated, thus accounting for thousands of years of environmental impacts?

Chinese officials might be expected to reply with another argument that apparently redirects blame for climate change towards the developed world: more than 15 percent of its carbon emissions come from powering factories that make products for export. Foreigners are to blame for the climatic consequences of those emissions because it is they who benefit from those products.

This sort of argument has its place. After all, for many communities, most of their contribution to the climate crisis comes from their consumption of imported products or energy. (Hong Kong is a case in point: per capita emissions of greenhouse gases within the territory – so-called production emissions – are modest by developed-country standards, but if we count emissions from all of the imports that Hong Kong people consume – their consumption emissions – per capita emissions rise to be among the very highest in the world.)

But putting the blame on exports fails to take account of the extent to which China’s economic rise would not have been possible without the developed world consuming its exports. Income from those exports substantially explains why China now has millions of millionaires, more than any country except the United States, almost as many billionaires as the United States (which it may overtake soon), and 700 million middle-class consumers living more or less as well as people in the developed world. Because China’s exports also benefit Chinese people, the responsibility – and the blame – for the environmental consequences of producing them must be shared by China itself.

The exports argument also ignores the fact that a quarter of China’s emissions are the result of producing cement and steel for highways, bridges, bullet train lines, airports, apartment blocks and office towers inside the country, not to mention warships and other military hardware that hardly benefits foreigners.

The bulk of China’s contribution to greenhouse gas pollution has occurred in the last several decades. At first this this appears to justify Chinese arguments that the developed world should shoulder most of the blame for climate change.

However, attributing blame in that way would ignore the undeniable fact that for almost the entire period during which the developed countries were producing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions, they did not know that what they were doing would lead to global warming and climate change. It was only in the late 1980s that the science of climate change developed policy relevance. The first major international scientific report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was published in 1990.

One can make a strong case that developed countries should have moved full speed ahead once they knew that burning fossil fuels was heating the planet. They deserve to be blamed for not doing much more, much sooner. Historical ignorance is no justification for inaction now and in the future. However, surely that ignorance is a mitigating factor when laying blame for what occurred in the past. What matters is what the developed countries did after 1990.

This brings us to China’s economic emergence and rise to become the world’s largest source of greenhouse gas pollution: most of that rise, and the vast bulk of the climate-changing pollution to come from it, occurred after the climate science was clear. In other words, nearly the entire time that China has been pumping massive and growing quantities of greenhouse gas pollution into the atmosphere, its leaders have been fully aware that doing so would contribute to climate change and thereby bring suffering and death to millions of people around the world.

None of this means that China deserves all of the blame for climate change, or even the majority of it. But it does mean that China shares much more of the responsibility for causing the climate crisis than Chinese officials want us to suppose. With that greater responsibility for the causes comes greater responsibility for implementing solutions.

Future generations will surely blame the United States and other developed countries for the degraded environment that will be bequeathed to them. But they may attribute even more blame to China because its leaders knew that they were creating an economic powerhouse and solidifying their power at the expense of the future.

For more than three decades, Chinese officials have pointed the finger of blame for greenhouse gas pollution at the developed world. They’ll do it again at COP26. But their arguments are wearing thin. Alongside the developed world, China deserves to be blamed for the climate crisis, too.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.