Hong Kong’s legislature has passed a bill which will enable the government to ban films deemed contrary to national security from being screened and published in the city. Any person who exhibits an unauthorised film could face up to three years in jail and a HK$1 million fine.

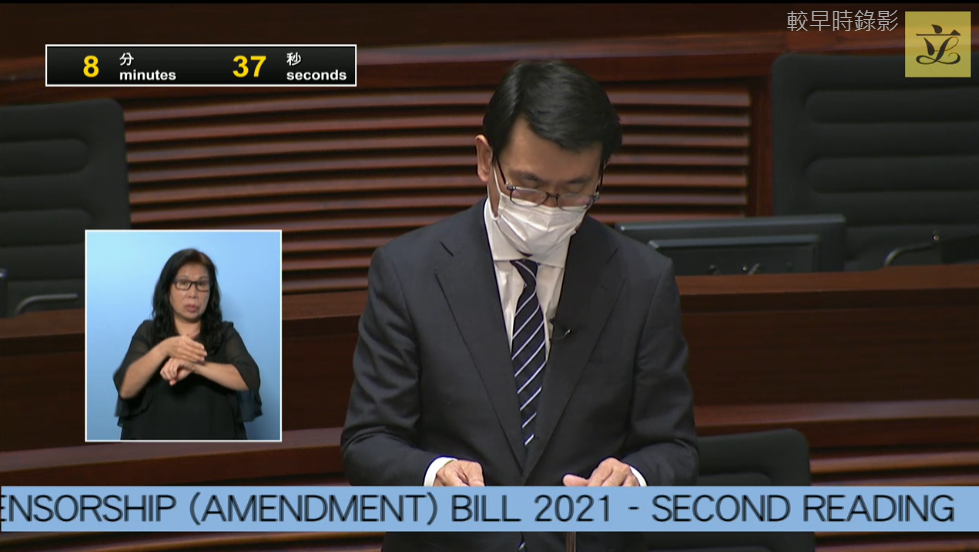

The proposed amendments to the Film Censorship Ordinance were approved on Wednesday with landslide support from pro-establishment lawmakers during their last meeting in the sixth Legislative Council (LegCo) term.

The new law will require film censors in Hong Kong to evaluate whether the exhibition of a film would be “contrary” to the interests of national security before allowing it to be screened locally.

The city’s chief secretary, a member of the Committee on National Security, will gain sweeping powers under the new law to instruct the Film Censorship Authority to revoke approvals granted – at any time – if they believe the presentation of a film will harm national security.

An inspector authorised by the censorship agency may also enter and search premises without a warrant when they are trying to halt an unauthorised film screening or publication, if it is “not reasonably practicable” to obtain a warrant.

Heavier penalties will be imposed on those who show films that are not exempted or approved by the authorities, as the offence is punishable by up to three years in prison and a maximum fine of HK$1 million.

Local film censors may ask for up to 28 days to review films that may involve national security considerations. Filmmakers may not challenge the censorship body’s decision, as the new legislation will bar the Board of Review from reconsidering decisions made on national security grounds.

The new stipulations came months after Hong Kong director Kiwi Chow debuted his documentary “Revolution of Our Times” at Cannes Film Festival in July. The film about the 2019 anti-extradition bill protests did not apply for exhibition in Hong Kong and it was slammed by local Beijing-backed newspapers as advocating independence, an offence under the national security law.

Other documentaries related to the 2019 unrest, including “Inside the Red Brick Wall” about the siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, have been pulled from commercial screening.

Online streaming

In urging the lawmakers to pass the bill, the government said in a LegCo document that there were films portraying national security offences and depicting “serious criminal behaviour.” The overall content, context and arrangement of these films would deliver the effect of “endorsing, “glorifying or inciting” people, especially youngsters, to commit those acts.

Some legislators raised concerns that the new law only targeted traditional forms of screening without addressing showings on streaming platforms like Netflix. Luk Chung-hung of the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions said some films disapproved by the censorship body may be described as “banned films” by streaming sites to attract attention.

“The framework of the ordinance is outdated… I am worried this may become a major loophole in the future,” Luk said.

In response, Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development Edward Yau said the suggestions to regulate films shown online would be outside the scope of the bill. He said the government would need more time to “carefully and comprehensively” consider adding further changes to the local film censorship system.

When asked if YouTube or other online platforms would be affected, a spokesperson for the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau told HKFP in August that “other” laws apply to the internet.

“[TV] broadcast and the Internet are subject to other applicable law and regulations. Whether an act constitutes a crime or otherwise would depend on its specific circumstances and evidence, and cannot be taken in isolation or generalised,” they said.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team