A Hong Kong man with a history of mental illness may soon be executed in mainland China, where he was sentenced to death in 2017 for drug trafficking. His elderly parents are now in Shenzhen waiting for their first – and perhaps last – visit to him as they made a desperate appeal to the authorities to spare their son.

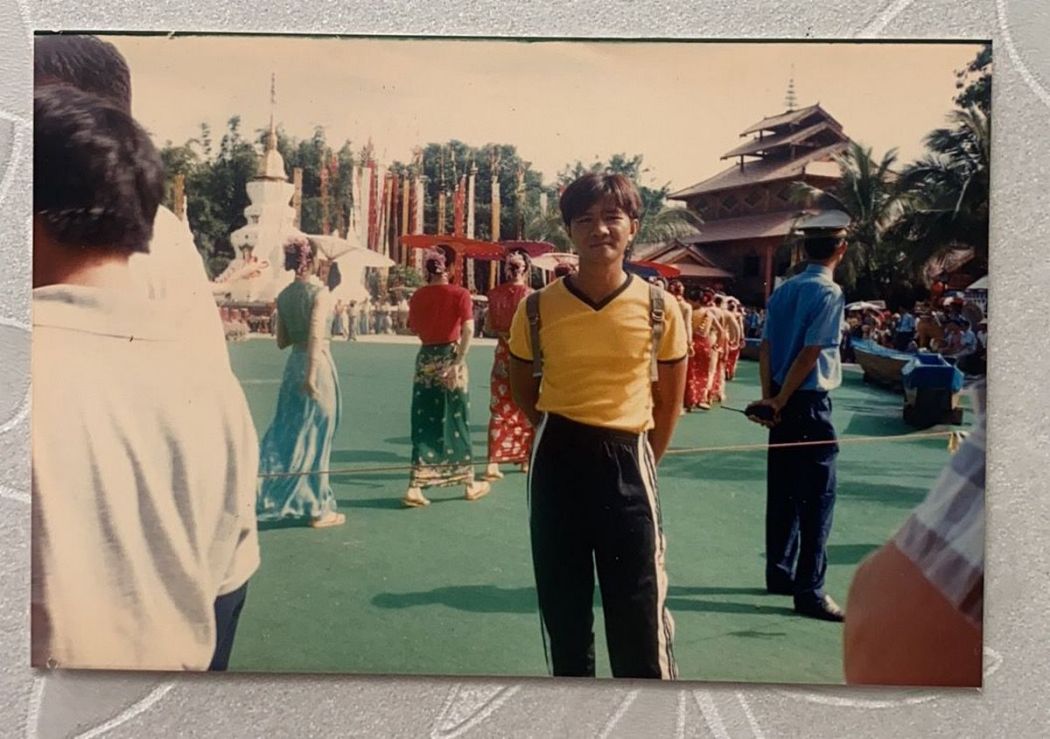

Fifty-year-old Wu Chi-man has been on death row for almost five years, after he admitted dealing 15 kilograms of methamphetamine in Shenzhen in March 2016. He appealed against his sentence in late 2017 but it was upheld.

Wu’s family had not seen him for years until they were notified by mainland authorities about three weeks ago that a meeting could be arranged next Thursday. Believing it may be the only chance to see him, Wu’s 80-year-old father and 78-year-old mother packed their bags quickly and brought along bottles of medication they needed for their indefinite trip to Shenzhen.

“We are quite helpless and clueless, we don’t know what will happen. Everything is still uncertain,” Wu’s father told HKFP by phone on Wednesday, when he and his wife were five days away from completing the 21-day compulsory Covid-19 quarantine.

“Chi-man is not an evil man. He only failed to resist the temptation and committed the crime because of poverty…”

Wu Chi-man’s mother

Wu’s parents have sought a retrial and appealed for a more lenient penalty, saying their son’s psychiatric history was not considered by the mainland courts. In a letter to the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing in November last year, with copies to Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam and the Immigration Department, Wu’s mother cited hospital records to show that her son has suffered from polysubstance abuse, hallucinations and adjustment disorder, among other mental health issues.

“Chi-man is not an evil man. He only failed to resist the temptation and committed the crime because of poverty… and he was troubled by his long-term mental issues,” Wu’s mother surnamed Chan wrote in the letter. She also appealed for a lighter sentence on the basis of his guilty plea and the fact that he had no prior criminal record in the mainland.

Speaking to HKFP by phone, Chan choked up when she was asked about the upcoming meeting with her son. She said she fears that her son, who has been known to mental health services in Hong Kong since 2000, may not be receiving any appropriate psychiatric treatment whilst in detention.

Chan said her husband told her to hold back her tears when they visit Wu next week, so that he “would feel better.” She said the five years Wu spent in detention “were very difficult,” pleading with the Chinese authorities to give him “a chance to correct himself.”

“We hope the authorities could give him a way out… I don’t want us, the silver-haired, to watch the younger one pass away,” she said.

China was named the world’s leading executioner by Amnesty International in its annual report on the death penalty published in April. But the true extent of the use of capital punishment was unknown as such figures were classified as a state secret, it said.

In response to HKFP’s enquiries about the number of Hong Kong citizens sentenced to death in China between 2016 and 2020, the Security Bureau said it did not have such figures.

It remains unclear why Wu’s mental health history was not mentioned in the trial or the appeal, said Hannah, a volunteer from a group called Voice for Prisoners who has helped with Wu’s case since September last year. The NGO volunteer, who used a pseudonym in fear of reprisal, said Wu’s appeal letter made no reference to his medical condition.

In urging the High People’s Court of Guangdong province to revoke the death penalty, Wu’s lawyer said there was another suspect in the case who was never arrested, according to a court document seen by HKFP.

It was therefore “extremely unfair” to sentence Wu to death, the lawyer said, as the lower court did not examine the roles played by Wu and the suspect on the loose, and their respective degree of criminal liability.

Hannah, who assisted Wu’s almost-illiterate mother in penning the letter to the authorities, said they reached out to the Immigration Department’s hotline again before Wu’s parents left for Shenzhen. The agency, however, said it did not have the expertise or authority to offer much assistance, except to provide information on how to obtain health codes needed for travelling to the mainland amid the pandemic.

In response to HKFP’s enquiries, the immigration department said it had flagged Wu’s situation to the Beijing Office and Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in Guangdong. The department would “maintain close contact” with the family and “render all practicable assistance,” it added.

The Hong Kong Joint Committee on the Abolition of the Death Penalty filed a petition to the China Liaison Office in Hong Kong on Tuesday last week, urging the Chinese authorities to halt Wu’s execution and grant him a new trial. They also asked Chinese leader Xi Jinping to pardon Wu.

“It would be unfair for [Wu] to be sentenced to death in the absence of a mental health assessment and a fair trial,” the group said.

It may be a systemic failure. With better support, not only medical but social… maybe he would not have fallen for quick money. I guess that’s my biggest takeaway.

Hannah

John Wotherspoon, an Australian priest in Hong Kong who offered assistance to Wu’s family after meeting them last year, told HKFP the case calls for better communication between the authorities in the city and in China when Hongkongers are detained across the border.

“It’s good for everyone. It clears up uncertainties and doubts, and makes everything more transparent. The idea of people being imprisoned, being out of touch and communication, that whole area should be transparent for everybody’s sake,” said Wotherspoon.

It is widely understood that those on death row in mainland may face execution shortly after they are offered a chance to see their family, Hannah said. She hoped Wu’s case would show the city that it needs to pour more resources into supporting those with mental health problems.

“It may be a systemic failure. With better support, not only medical but social… maybe he would not have fallen for quick money. I guess that’s my biggest takeaway.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.