Vo Van Hung has lived behind bars for 27 years, ever since he was 15 years old.

A Vietnamese refugee, Vo killed a man in a Hong Kong refugee camp. He was convicted and finished serving his time in 2016. Yet now, five years later, he’s yet to taste freedom, caught up in a nightmare Hong Kong government bureaucratic limbo that appears to have no end in sight.

Vo, now 42, spoke to HKFP in early September from behind a plexiglass barrier in the visitor’s room at the high-tech “smart” Tai Tam Gap Correctional Institution, where he is now being held indefinitely. A lean-figured man with high cheekbones and a closely-clipped prison haircut, he recounted the details of his story.

Vo came to Hong Kong from Vietnam by boat in 1991 when he was 12, brought by an “elder brother” whom he had never met before. The “brother” dropped Vo in Hong Kong and abandoned him.

He ended up in the Whitehead refugee detention centre in Ma On Shan. It was an unfortunate time to arrive in Hong Kong. The government had begun forcibly repatriating Vietnamese in 1988. Whitehead’s tens of thousands of refugees faced an uncertain future, and in 1994 that tension erupted in a riot that ended with police shooting 500 rounds of tear gas into the immigration centre.

Against this tense backdrop, 15 year old Vo got into a fight with another refugee. He stabbed him, and the man died. Justice came down so swiftly and hard that Vo, not knowing a word of Cantonese or English, only found out he’d been handed a life sentence years later, from the other inmates. That life sentence was later replaced by a 29-year prison term in 1998, when Hong Kong amended its laws that barred minors from being sentenced to life.

Vo was set to be released from prison in 2016 after serving his time. But once again Vo found himself a victim of unfortunate timing: He is not a Hong Kong resident. Because of his incarceration, he had missed the windows of opportunity that allowed other Vietnamese refugees over the years to legitimise their Hong Kong status. When his term for murder ended, Vo was moved to a second incarceration, at the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC).

No one has told Vo Van Hung when his detention will end. Weeks have turned into months, and months into five years.

Vo’s Kafka-esque tale took an even more bizarre twist this past summer. “They didn’t say why, but just suddenly told me to pack up my things,” Vo said. With no advance notification, Vo was transferred last June to the Tai Tam Gap Correctional Institution (TTG), which has been renovated as one of the first “smart prison” facilities in a Correctional Services Department (CSD) initiative supported by Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

The Tai Tam Gap facility was repurposed as an immigration detention facility at the end of May 2021, but it is run by CSD. The flagship of Hong Kong’s new “smart prison” program boasts stricter rules and restrictions, along with high-tech innovations–including biometric tracking–that all but eliminate privacy. Vo told HKFP that his life in Tai Tam Gap is much worse than when he was in prison custody, or when he was detained at CIC in Tuen Mun.

And Vo still has not been told when, or even if, he will be released from his limbo.

A legacy of uncertainty, incarceration and deportation

The Hong Kong Immigration Department has been trying to deport Vo Van Hung to Vietnam since he left prison in 2016.

From the time that the first Vietnamese refugees arrived on Hong Kong’s shores in 1975, the government has opposed their immigration and encouraged them to leave, a policy reflected in the statistics. While more than 200,000 Vietnamese people arrived in Hong Kong between 1975 and 1999 fleeing the communist government. 143,700 were resettled in other countries and more than 67,000 Vietnamese migrants were repatriated.

As of 2021, the Security Bureau said there were 18 Vietnamese nationals deemed ineligible for local resettlement for reasons including imprisonment. Vo appears to be one of them.

“I was in prison because I had committed a crime and had to pay for that bill,” Vo said. Now that his debt to society is settled, Vo anticipated that he’d have a chance to start a new life in Hong Kong.after over two decades in prison. He was not expecting to face further frustration and incarceration, waiting as his case got passed from one bureaucracy to another without resolution.

Vo arrived for his meeting with HKFP wearing an orange jersey and carrying a hefty stack of papers under his arm, documentation of his long ordeal. To fight against deportation, he filed a non-refoulement claim, arguing that he may face persecution in relation to his father’s background, or that would be held liable for leaving Vietnam illegally.

His case was rejected. A High Court judge ruled in his favour in August 2019 after he challenged the Torture Claims Appeal Board’s decision with a judicial review. The board had failed to fully examine the risks he may face if deported to the country, the judge said, and his case was knocked back to the board. After another hearing in June, however, the board once again rejected his claim. Vo is now taking steps to file a second judicial review.

Vo was encouraged when pro-bono lawyer Mark Daly took an interest in his case. But even there, he hit a bureaucratic wall: to get the lawyer involved, Vo had to apply for legal aid and he is still waiting for a decision on an appeal heard in June. If his legal aid is approved, Vo can then have the lawyer file for an order for his release from detention.

‘Smart Prison’

Vo, with more than two decades of incarceration in Shek Pik and Stanley under his belt, did not hesitate when he told HKFP that being in Tai Tam Gap is “much worse” than his prison stint. “At least you have something to do in prison. Here, you are held in a room for 12 hours a day, and are only allowed to go out[doors] for an hour,” Vo said.

Detainees in TTG are awoken every day at 6:30 a.m. and brought over to a communal day room from 7 a.m. until evening. In the day room, activities are limited–inmates take turns to watch television or read newspapers.

Work or study programmes available to prisoners are not available at immigration detention centres. Days drag on in extreme boredom. Detainees are allowed just one 15-minute visit per day.

“It is as if we are kept as dogs or as pigs, waiting twice a day to be fed,” Vo said.

Unlike the CIC, which is operated by the Immigration Department, TTG is operated by Hong Kong prison authorities. “CIC was not as strict as here. Those officers were nicer and communicated better,” Vo said.

Formerly a prison, TTG was closed in mid-2018, refitted with “smart prison” features, and reopened in late May 2021 as an immigration detention centre for up to 160 inmates. It currently houses 67 detainees. Along with Pik Uk and Lo Wu prisons, TTG is the third testing ground for Hong Kong’s ambitious high-tech detention programme.

Tai Tam Gap is classified as a “minimum security” facility. However Vo and the other “smart prison” detainees are required to wear “smart wristbands” –black iWatch-like devices without display screens. The wristbands record detainees’ heart rate, respiratory rate and blood oxygen level, emitting an intermittently flashing green light. But inmates can’t take this watch off, nor see any of the data it’s constantly collecting from their bodies.

The devices also track detainees’ location within the facilities, in real time. Besides the wristband trackers, rooms in the detention facility–even the toilets–are lined with surveillance cameras.

Anna Tsui is a member of the grassroots CIC Concern group, which focuses on immigration detention. She said the tracking devices raise serious privacy rights concerns. “If I was wearing a handcuff, I would know what it is and its function is to restrain me. If I’m made to wear a device, I should be entitled to know what it’s for,” she said. “It’s not like [the detainees] have signed up to a smart programme to have their data collected voluntarily.”

Despair and unrest

Despite its much touted advantages, the smart prison initiative got off to a bumpy start. Since TTG’s opening in May this year, the CSD has had to “combat illicit activities of detainees” three times: in June, July and again in August.

In June, according to a CSD press release, a detainee allegedly “provoked the officers” over a television programme. He was punished with detention, and 23 detainees joined a hunger strike to demand his release. Then, on July 3, a group of detainees started a fight in the communal area and were subdued by officers using pepper foam. Four were “detained” as a result–including Vo Van Hung. “Some friends got caught up in an argument, so I tried to help them,” he said.

About seven weeks later in August, detainees again refused to obey orders, according to CSD, and 12 were detained in solitary confinement pending investigation. In all three instances, the CSD deployed top-tier anti-riot officers from its Regional Response Unit — dubbed the “Black Panthers” — to quash the unrest.

Vo’s solitary confinement punishment lasted an extraordinary 56 days — double the amount of time allowed under Hong Kong’s Prison Rules for the punitive measure. (The United Nations defines long-term solitary confinement as putting a person in sole custody for over 22 hours a day, during a period of 15 days or more.)

“It is as if we are kept as dogs or as pigs, waiting twice a day to be fed.”

Vo Van Hung

Vo thought some detainees showed more resistance to officers than when they were in prison, because they were no longer prisoners, and believed their detention to be unfair.

Experts and advocates familiar with immigration rights say the decision to detain these immigrants, along with the unusual length of these detentions, both need to be justified.

Preston Cheung of Justice Centre, a non-profit group that supports refugees and immigrants’ torture claims, cited the “Hardial Singh” legal principle, a concept which states that claimants may only be detained for a reasonable period, and that immigration should not seek further detention if it becomes apparent that the department is not able to deport the individual within a reasonable period. The Security Bureau said as recently as February that it would act in accordance with such a principle.

“Whether a person’s non refoulement claim is meritorious is a separate issue to whether their detention period is reasonable,” Cheung said. “The Immigration Department has been trying for five years to deport [Vo] without success. That does not seem to be a reasonable amount of time.”

Tsui, of the CIC Concern Group, said she heard from detainees that many gave up on their non refoulement or torture claims after being transferred to indefinite stays at TTG.

“Those who have held up emotionally are the minority,” she said.

In response to HKFP’s enquires, the Security Bureau said the Immigration Department take into consideration whether an individual committed serious crimes or may cause a security risk to the community when determining whether they would be granted release from detention.

The reason to deploy the TTG detention centre, the bureau’s spokesperson said, was to increase the general space to house immigration detainees who had committed certain crimes or are considered to be of higher security risks. “Individuals detained at both [CIC and TTG] centres receive similar treatment,” their statement said.

“If detainees are discontent with treatment they received during detention, they may file complaints via various channels.”

The ‘family’

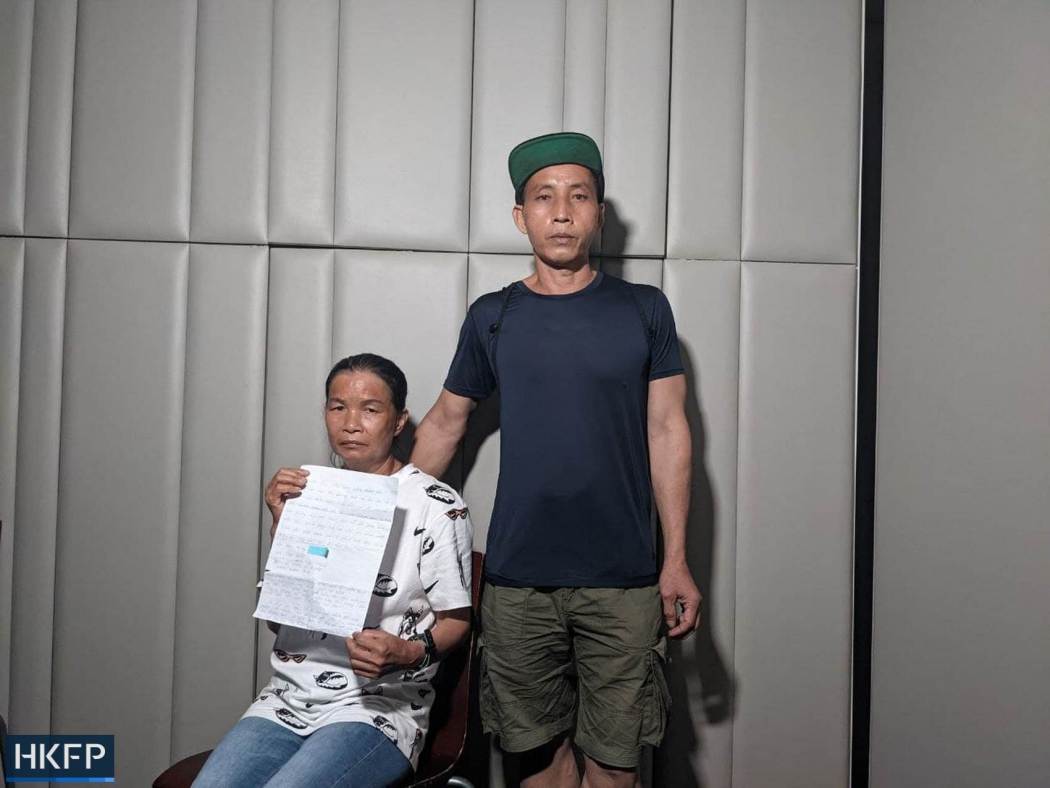

Vo has had one bit of good fortune come his way while in custody. Auntie Fan, the mother of a former detainee, learned about Vo during her prison visits in the 1990s to see her own refugee son Vu Va Leo. Over decades, Auntie Fan and Vu became Vo’s “family,” and Vu and Vo consider each other to be brothers.

Vu is now free–he was released from prison years earlier at a time when it was still possible for Vietnamese to claim asylum status. He said Vo learned to speak, read and write in Chinese and in English behind bars. “When we were together [in prison] he said he wanted to study, so I said I will send you money to join courses for whatever you like.”

“The day after I was released from prison, I immediately went to ask if I could be [Vo’s] guarantor for bail,” Vu said. “But they said no.”

Despite solid and compassionate support from his adopted family, Vo fell into despair two years ago and attempted suicide by taking dozens of sleeping pills gathered and given by other detainees. He was hospitalised for several days, Auntie Fan said. “The immigration did not tell us that he was in the hospital when we tried to visit. They claimed they didn’t know where he was,” she said.

“My heart ached so much knowing that he wanted to give up.”

Although his ongoing legal cases offer promise of an eventual resolution, the slow, grinding days of limbo at Tai Tam Gap are taking a toll. Vo said his heart is slowly losing hope that he will ever be able to live as a free man in Hong Kong. “I committed a serious crime when I was young because I was immature. I paid the cost and bore the responsibilities,” he said.

“It’s not fair to treat a bad person as if he was a bad person forever.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.