By Georgia Leatherdale-Gilholy

After an almost 20-year war – the US’s longest – President Biden has announced that US and NATO troops will complete their withdrawal from Afghanistan by August 31st.

America’s war may be almost over, but Afghanistan’s conflict won’t be.

The cycle of violence and humanitarian crises that have recently characterised the so-called “Graveyard of Empires” long predates the 2001 invasion. They are the product of a complex cocktail of regional rivalries and competing ideologies, both of which have been exacerbated by the strand of violent Islamism behind the 9/11 attacks; the perpetrators of which were hand-picked at al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan.

The US bears much responsibility for the latter’s presence in Afghanistan in particular, given that its ‘Operation Cyclone’ facilitated the arming and funding of mujahideen forces, the part-rival and part-predecessor of the Taliban, throughout the ill-fated Soviet invasion.

Yet whatever the US’s historical responsibilities in the region, the argument over intervention is essentially over. After decades of war, over a trillion dollars in expenditure, and thousands of casualties, the American voter, understandably, does not support further intervention.

While the impact of Afghanistan’s unravelling remains to be seen, it has spurred a curious mix of anxiety and opportunism amongst its neighbours, and China is no exception.

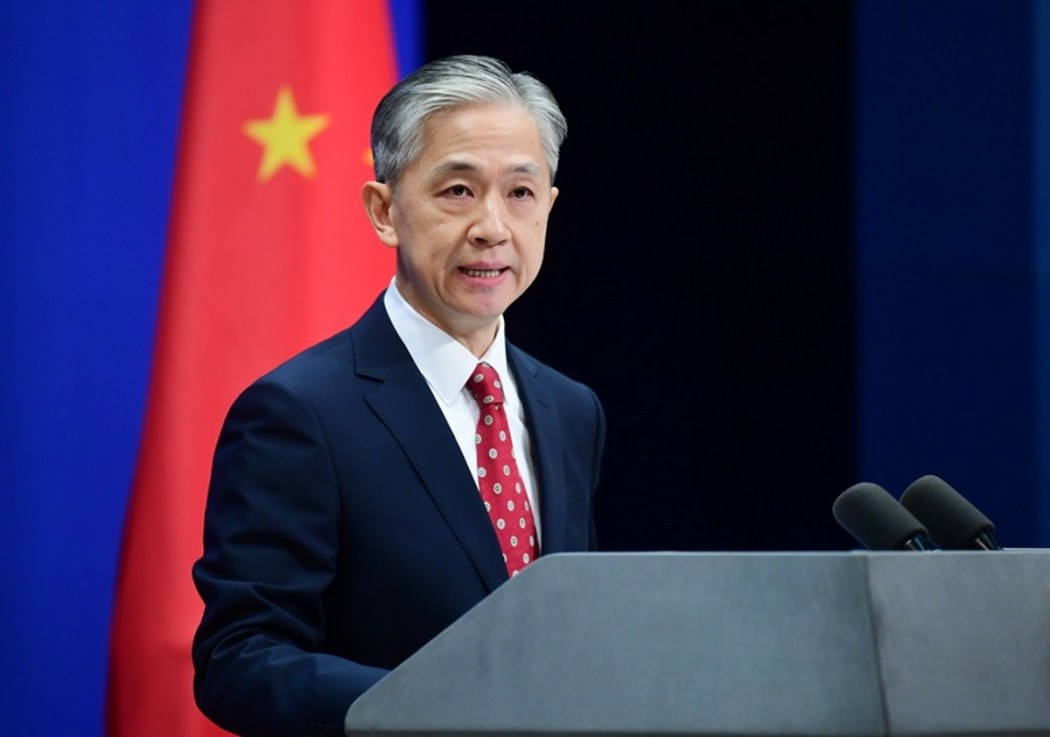

Nor, it is clear, does China waste any time. A Taliban delegation met with Foreign

Minister Wang Yi in Tianjin on Wednesday.

Evidently aware of its crumbling military consensus, and increasingly less concerned with toeing the US’ line, the government in Kabul has reportedly been engaging with Beijing regarding the construction of the Peshawar-Kabul motorway, which would connect Pakistan to Afghanistan and initiate the latter as the latest member of China’s Belt and Road scheme.

Beijing is already building a road through the strategically important Wakhan Corridor—a narrow, mostly mountainous strip of territory that links China’s westernmost province of Xinjiang to Northeast Afghanistan—and onward to Pakistan and Central Asia, complementing the region’s existing road networks.

Upon completion, these new thoroughfares would enable Beijing to pursue increased trade with the region and pursue the extraction of Afghanistan’s wealth of natural resources. While more than half of all existing ‘rare earth’ mineral supplies, materials required for the manufacture of high-tech devices, are currently mined in China, Beijing is keenly aware of the finiteness of these reserves and is aware that Afghanistan may possess almost a trillion dollars’ worth.

But what might the future of these projects be if the Taliban does indeed oust the government in Kabul? Can a regime currently interning and persecuting an estimated 1 million Uyghur Muslims, really strike a deal with an Islamist terror group seeking to establish a divinely ordained caliphate? Is wooing proven hypocrites such as erstwhile party boy Imran Khan, not an entirely separate thing to negotiating with Islamist insurgencies?

It seems the path is less complicated than we might think, and indeed the Taliban has already begun making deliberate overtures to Beijing. Not only have they refused to condemn the ongoing atrocities against their cousins in bordering Xinjiang, but they have announced that they would outlaw any Uyghur militants within their territory.

Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen also told Agence France-Presse, that “If any country wants to explore our mines, they are welcome to. We will provide a good opportunity for investment.”

Yet, in no sense is China necessarily cheerleading the US withdrawal. Just last month Beijing’s foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin claimed that the US was “disregarding its responsibilities and obligations… leaving a mess and turmoil for the Afghan people and regional countries.”

Of course, the sincerity of all statements by Chinese government officials must be taken with a grain of salt, it would seem that an Afghanistan rendered more militarily stable by American troops, but still open to Chinese economic exploitation would be the best of both worlds for Beijing.

Instead, the Taliban’s current rapid expansion across Afghanistan depressingly mirrors the mayhem that accompanied the advent of ISIS after Obama’s withdrawal from Iraq. The group have already captured over 120 of the country’s 387 districts, the country’s main border crossings and transit routes with Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, Iran and Pakistan, essentially laying an economic blockade around the country. Without the backing of the US military, Kabul looks set to collapse in months.

While this trajectory will surely spell chaos for China’s plans for Afghanistan in the short-term, once the dust has settled, Beijing may well be grateful for the lack of American obstacles to its plans in Afghanistan.

Georgia Leatherdale-Gilholy is Editor-in-chief for Foundation for Uyghur Freedom and a Young Voices contributor.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.