by Sebastian Skov Andersen and Thomas Chan

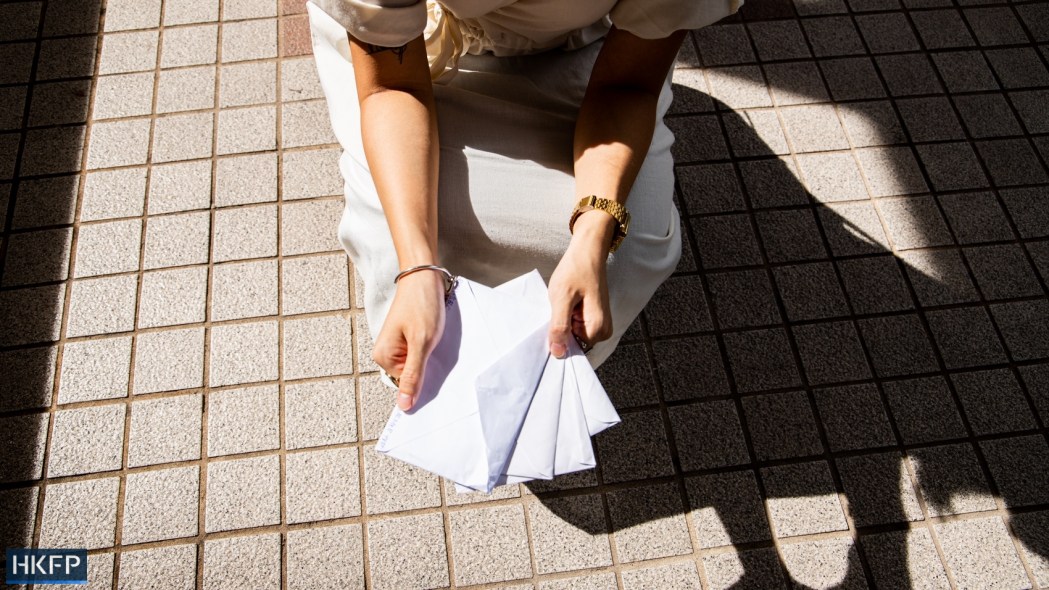

The first thing District Councillor Fleco Mo does when he arrives at his office in the morning is to make a cup of coffee. The second thing he does is to find a pen and paper, then he sits down and writes long, uplifting letters.

The address on the envelope is a prison, a cell, and the name of an imprisoned protester from the 2019 pro-democracy rallies. He attended many of their court hearings from the beginning, and most of them he “sent off” to prison by running alongside the prison transport as they were driven away from the courtroom.

“We need to finish what we started… It was a red hot movement, but there were bound to be side effects, and the mass arrests are one of them.”

District Councillor Fleco Mo

Mo is the creator of a community group that consists of about 20 members who work to offer support to protesters throughout the entire process of their imprisonment, from the moment of arrest until their release.

The volunteers are known as Hong Kong’s “Masters of Letters” for their dedication to making sure imprisoned protesters don’t end up like “dong sau juk hai condom”, meaning to treat protesters like condoms — disposable and thrown away after use. But they do not accept praise. “It’s the least we can do,” said Mo.

Exactly one year ago, the national security law changed Hong Kong fundamentally in a matter of days by outlawing dissent in the city. Since then, prominent activists have featured on the front pages of the world’s newspapers, as they were either imprisoned or forced into exile, one after another.

In all, more than 10,000 people have been arrested and 2,500 are being prosecuted in relation to the 2019-2020 protests, mostly for offences like rioting or unlawful assembly and a few — but increasing — for offences under the National Security Law.

The clear majority of detainees attract little attention from the media or the public, their trials just another line on a busy court sheet, and reports indicate that many struggle with isolation and disillusionment while serving their sentences. As a “thank you” for putting their futures on the line for the pro-democracy movement, Mo and the rest of the group try to make the inmates’ time behind bars as pleasant as possible.

The group’s work began when relatives of imprisoned protesters from his constituency reached out to Mo because they needed help completing their exams from behind bars. “We would send them past papers and help them with answers — that’s how we got started,” he said. “Even in prison, they still care about their exams, and they have no one else to help them there.”

Initially, Mo encouraged people from his constituency to send letters to him and then passed them on to inmates without establishing an ongoing relationship. One person even sent in a letter written on the blank side of a restaurant menu card about the news they had read that day, said Mo, giving everyone a laugh.

Soon, the work evolved into a sophisticated support system for protesters facing prison time, beginning with a buddy system where volunteers were paired up with an inmate to become pen-pals. “The longest sentence of a pen-pal is 12 years,” said Mo, but he is worried that sentences given in the future under the NSL could be longer.

Some friends on the inside are worried about me… When, on occasion, I’ve sent a letter late, I have gotten replies that they were scared that I had been arrested

letter-writer Katie Cheung

“When the protesters receive our letters, they’re overjoyed,” said Mo. “There’s this guy I visited recently, who has more than a dozen pen-pals. He loves writing letters. It’s at least something to spend his time doing, and he looks forward to it because it gives him a connection to the outside world and a medium to learn what is happening on the outside that is not a newspaper.”

It quickly became clear to Mo that he had found a vacuum that needed to be filled, where people could go to for support if they or a relative were facing imprisonment. There was no shortage of volunteers who wanted to help fill that vacuum.

Today, the group has taken on a bigger responsibility, where members enter into sometimes years-long relationships with inmates. The group doesn’t only write letters anymore, and volunteers often follow convicts throughout their trials and “send them off” when they’re taken to prison. Some even visit inmates at the prison if allowed to.

They have also started collecting “gifts” — everyday necessities and entertainment objects like pencils, books and toothbrushes — from the community to send to inmates, advocating for prisoner rights, striking deals with manufacturers to produce goods that won’t be confiscated by correctional officers if sent to inmates, and by offering support to family members.

To the members of the community group themselves, it is an opportunity to soothe a feeling of guilt over not doing enough.

“This sense of guilt, it’s shared by everyone. By the frontliners and the ‘wo lei fei’ [peaceful protesters] — by everyone who believes in the movement,” said Mo. “By doing this work, people have a means to contribute to the movement by supporting the convicts. For the people who didn’t even have the courage to join the peaceful protests especially, they feel indebted to protesters on the frontline. With this, they can compensate for this sense of guilt.”

“We need to finish what we started,” Mo told HKFP. “It was a red hot movement, but there were bound to be side effects, and the mass arrests are one of them.”

Katie Cheung (not her real name) has been a member of Mo’s community group for over a year now, since the very first batch of arrests in the early days of the protest movement. “If I get arrested one day, I also want people to care about me,” she said when asked why she had signed up for Mo’s group. She mostly does work writing letters to inmates, but also attends court hearings and attends “send-offs” on occasion.

So far, her pen-pals have mostly stayed in touch with her for a short while, until eventually signing off with a “no need to reply anymore la, I’m coming out” and then going off grid. Still, the workload is ever-increasing these days, as more protesters get convicted. “To say it in a sadder way, there will always be someone to write to,” said Cheung.

But she has also built a more meaningful relationship with one inmate, with whom she has corresponded for a year-and-a-half and hopes to stay friends with after he’s released. “He told me in a letter that it was a great thing to have a companion during his time in prison,” she told HKFP. But the praise that comes with the gig is lost on her.

“It’s something everyone can do if they want. I am just an ordinary person, not a professional,” she said.

But the support for protesters on trial and the lack of transparency in the ruling process has grown so substantive that volunteers need to commit entire days if they want to attend. Queuing for entry can take hours because of the number of people there, and sending off the correct prison transport is all about waiting until the correct vehicle leaves.

“They come out quite irregularly and you don’t know which vehicle it is, so you just run and send all of them off anyway,” said Cheung. “Sometimes you’ll spend hours there but only five minutes of them actually matter.”

Running after a van

“It’s hard for me because I just want to cry when we send people off. When you’re running, the vehicle will be gone after a few seconds, and then the emptiness and helplessness. You never know when you’ll see the prisoner again,” she added. “But it’s all worth it as long as they see our presence and support, even if it’s just for a second.”

Wall-Fare, a prisoner rights advocacy group which was founded by former member of the Legislative Council (LegCo) Shiu Ka-chun following his imprisonment in relation to the 2014 protests, is a rights group that advocates for better conditions in Hong Kong’s prisons and does much of the same work as Mo’s group.

They too have a pen-friend programme, collect “gifts” for inmates (everyday necessities like pencils and toothbrushes) from the community, attend hearings and send-offs, and hold counselling sessions for relatives, but they also run larger campaigns to put political pressure on the authorities to improve conditions for prisoners.

Most recently, the group organised a campaign to cool down Hong Kong’s prisons during a heatwave in May that garnered more than 140,000 signatures. The petition received no official response from the prison authorities, but inmates tell Wall-Fare that prison staff provided extra fans and other accommodative measures, said Chaylen Hui, a social worker with Wall-Fare.

Hui herself attends court hearings on occasion, has about 15 pen-pals in prison, and takes part in these advocacy campaigns. But as the pro-Beijing wing tightens control over the city, requests fall on deaf ears increasingly often. “We can’t control whether the Department will listen, but at least it shows the prisoners inside that people do care about them.”

Since Shiu retired from LegCo, alongside 14 other pro-democracy colleagues in November last year, the organisation has had a particularly hard time pushing through changes because they can now only exert pressure from outside the system, Hui told HKFP.

This has created a climate where correctional officers are able to discriminate against prisoners who were convicted on protest-related charges. For example, members of Wall-Fare allege that letters sent to protesters are often intentionally delayed for up to two weeks.

Both sides of the wall

Likewise, deliveries and packages from the outside are often mixed up or tampered with, said Hui. She and other volunteers used to send updates and excerpts of popular shows on television to their pen-pals, but the detention centres have now banned that type of content without giving a reason.

“We can do advocacy work, but there’s nothing we can do to change reality. We don’t have that power, so the moment when we stop writing is when they no longer allow it,” said Hui.

For members of both Mo’s community group and Wall-Fare, the threat of facing consequences is increasingly difficult to ignore. Cheung generally uses a false name to sign off her letters to avoid being put on a watch-list by the police, and the group screens every letter before shipping them off.

Usually they manage to avoid censorship from the correctional officers by staying clear of topics that could land them in trouble with the authorities, but there is worry that the work itself could put them in the line of fire. The least-worst scenario as to how the prisoner support project will end, they worry, is for prisons to stop permitting letters from non-relatives.

What they fear most is that members will be arrested. “Some friends on the inside are worried about me,” said Cheung. “When, on occasion, I’ve sent a letter late, I have gotten replies that they were scared that I had been arrested.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.