Today is World Press Freedom Day. It is a day to mark the importance of freedom of the press and governments’ duty to uphold and respect the right of freedom of expression enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from 1948. This year also marks the 30th Anniversary of the Windhoek Declaration for the Development of a Free, Independent and Pluralistic Press that came at the end of a UNESCO conference in 1991. This declaration is the origin of World Press Freedom Day.

As we look back on 2020, and the first few months of 2021, the situation faced by journalists is in a very precarious position on all corners of the globe.

The World Press Freedom Index for 2021 was released last month. And, in Asia, the list of countries with serious press freedom issues is long. Singapore, Laos, Vietnam, China and North Korea all rank within the lowest category of “very bad” for press freedom. Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sir Lanka, and Thailand all rank in the second lowest category of “bad.”

Hong Kong falls into the category of “problematic,” and sits in 80th place out of 180 countries on the list for the second year in a row. But that position is also a drastic fall in the state of press freedom in the city over the last decades. In 2013, Hong Kong sat at 58th place, and in 2002 it came in at 18th.

The last few years have seen dramatic shifts in press freedom across Asia. Countries including Bangladesh, Laos, and Cambodia have all passed laws that make it illegal to criticize the government online or publish anything that could be seen as dissent. In 2019, Singapore passed the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulations Act that forces media outlets to post “corrections” to anything that the government may deem as “incorrect” or face steep fines on prison time. Thailand has used the threat of the country’s lèse-majesté and the possible 15-year prison sentence to deter journalists Hong Kong’s own national security law, while not even a year old, has had a chilling effect on the press in the city and gives both the Hong Kong government and Beijing broad powers. These laws have collectively resulted in ever expanding list of journalists either facing steep prison sentences or already sitting behind bars.

The outbreak of Covid-19 has further allowed the clampdown on the press through the use of these laws. By citing national security and attempts to stop the spread of “fake news” in the wake of the disease, autocratic leaders have been able to muzzle the press by expanding how the laws are implied. They have also been able use Covid lockdowns to stifle dissent by halting protests. Covid has also given these various governments cover in that the story of what they are doing gets lost in the shuffle, and few world leaders have been speaking out about the cases that do reach an international audience.

But it is important to remember that the state of Press Freedom is not just an issue in Asia.

According to the data compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) there are currently 430 journalists and media assistants imprisoned around the globe as of this writing. China leads the list with 73 journalists behind bars, followed by Saudi Arabia with 32, Egypt with 31, Myanmar with 31 and Turkey with 16. These numbers are also constantly increasing. I have even needed to update the data above during the course of writing this piece as more journalists have been sent to jail for their work, and new cases of journalists being imprisoned have come to light.

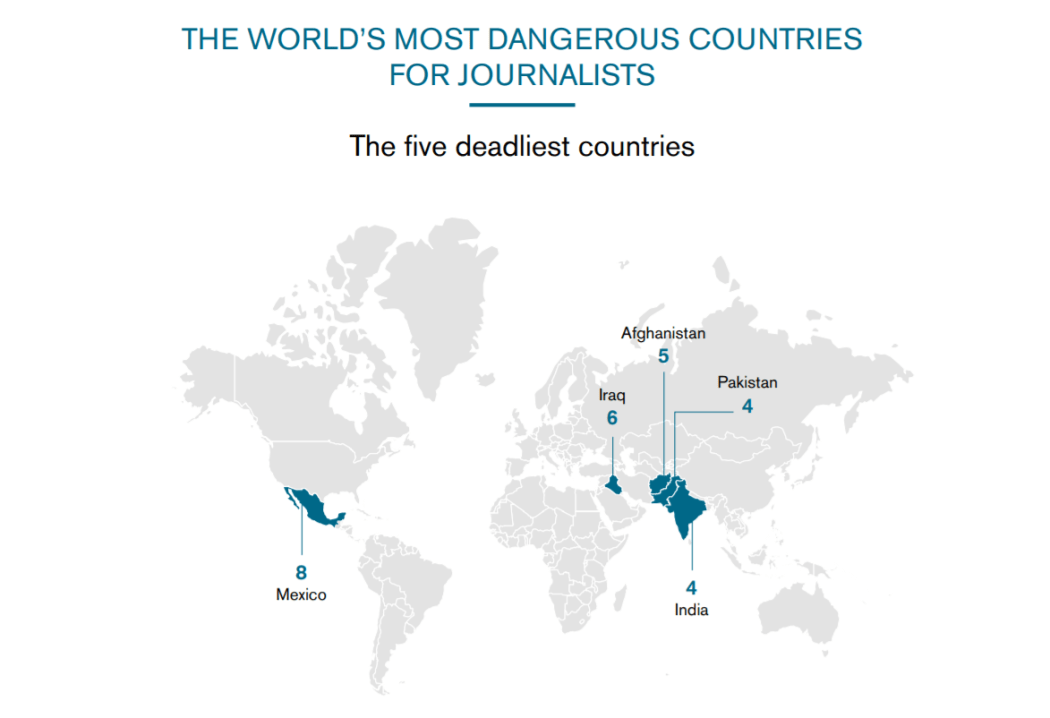

The RSF data from 2020 shows that 54 journalists were murdered last year. Mexico proved the deadliest country with eight murders. Afghanistan, India, Iraq, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Syria all had four murders each. Saudi Arabia (1), Bangladesh (1), Columbia (2), Egypt (1), Honduras (3), Nigeria (2), Paraguay (1), Russia (1), Somalia (2), Venezuela (1), and Yemen (2) filled out the list.

The International Federation of Journalists published their report on March 11 that puts the number of journalists murdered in 2020 at 65 across 16 countries. Mexico tops their list as well with 14. Afghanistan (10), Bangladesh (1), Cameroon (1), Honduras (1), Iraq (2), Pakistan (9), India (8), Paraguay (1), the Philippines (4), Russia (1), Somalia (2), Sweden (1), Syria (4), Nigeria (3), and Yemen (3).

And the deeper that one investigates the data gathered by various organisations, the more perilous the situation for journalists becomes. Even in what many consider democratic and open societies, incidents not only occur but have increased.

In the US, looking at data from the US Press Freedom Tracker, 416 journalists were assaulted in 2020 and 137 were arrested. So far in 2021 there have been 35 assaults and 29 arrests recorded by the tracker. Many of these incidents have come as journalists work to cover the protests that erupted across the States in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota in May of 2020.

All of this data does not count the number verbal attacks on the press or attempted murders of journalists. When all of those incidents are also taken into account, the attacks on the press worldwide are even more staggering.

Online attacks are also on the increase, especially against female journalists. A recent survey from the International Center for Journalists and The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) looked into online attacks against female journalists worldwide. 64 per cent or all white women journalists said they have experienced online violence. The rates for those identifying as Black stood at 81 per cent, Indigenous at 86 per cent and Jewish at 88 per cent. 41 per cent of the survey respondents said they had been targeted in online attacks that appear to have been the work of organised disinformation campaigns. The majority of respondents also stated that they had faced attacks aimed at smearing their reputations, faced accusations of spreading “fake news,” or attempts to spread false stories about their personal lives.

All of these numbers are not simply digits on a spreadsheet. Each one is a person with a name, a life and a family that has now been forever changed. The murder or imprisonment of a journalist does not happen in a vacuum. Nor do the physical attacks, online vitriol, and verbal assaults. The ripples of what happens to any journalist ebb out to affect all those who know them, work with them, and call them family members.

Just four full months into 2021, data from Reporters Without Borders has already noted 12 journalists and media assistants murdered for doing their jobs. But, like those numbers above, these numbers are also people. On World Press Freedom Day, we should know their names, and where they fell. It may not be much, and is in no way enough, but their names deserve to be known:

Adel Imaq Besmellah, Waheedi Mursal, Roufi Shahnaz, and Sadat Sadida in Afghanistan; Mushtaq Ahmed and Borhan Uddin Muzakkir in Bangladesh; Roberto Fraile and David Berinin in Burkina Faso; Kunchok Jinpa in China; Giorgos Karaivaz in Greece; Lokman Slim in Lebanon; and Jamal Farah Adan in Somalia.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.