By Francesca Chiu

In addition to fears for their families and for the future, many of the Hong Kong activists detained pending trial can face an immediate pressing problem: the need for funds to make prison life more bearable.

Strict rules against money-laundering have made it impossible for many opposition groups to fund them. So more and more are turning to a US-based funding platform called Patreon to support themselves on remand, including many of the 47 pan-democrats charged with conspiracy to commit subversion under the national security law.

In Hong Kong, detainees can if they wish pay for three private meals a day while awaiting trial. The cost of one month’s meals varies between detention centres but totals HK$7,500 at Lai Chi Kok which houses male detainees. At the female-only detention centre in Lo Wu, private meals for one month cost around HK$12,000. This shows how custody expenses can be quite high if detainees want basic options rather than just prison food. Detainees also need to pay for necessities, newspapers, and radios. This is where Patreon comes in.

The idea of crowdfunding is nothing new in Hong Kong. Traditionally, activists received public donations via affiliated groups for particular events. Every year except during the pandemic in 2020, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China organised a candlelight vigil on June 4, and it became one of the major fund-raising events for different pan-democratic political parties.

However, this form of traditional fundraising based on physical events and through political parties has been slowly transforming into online platforms and is no longer confined to political groups. Since the 2010s, political crowdfunding campaigns have become common in Hong Kong.

One of the most prominent was the “Wolf-Hunting Action” in 2018, in which Democratic Party members crowdfunded via an online campaign to raise at least HK$2 million to support an investigation into former chief executive CY Leung over his controversial UGL deal worth over HK$50 million.

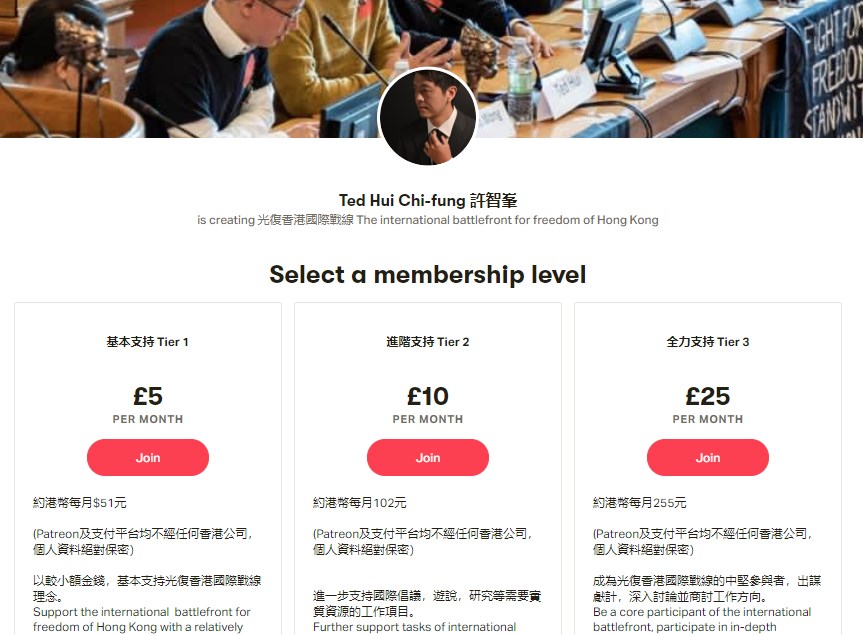

But project-based crowdfunding campaigns have since 2019 been at risk of incurring charges related to money-laundering. Police have arrested at least one protester from the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill movement who raised funds for his family. Ex-lawmaker Ted Hui had his HSBC accounts frozen when he was accused of money-laundering over a crowdfunding campaign to bring a private prosecution against a driver who allegedly rammed his taxi into protesters. This private prosecution was blocked by the Department of Justice.

Because traditional donations to activist groups, or just individual activists, increasingly risk charges of money-laundering, Patreon has become an alternative. Many jailed activists have opened a Patreon account to support their expenses during incarceration.

Patreon, originally designed to let fans financially support their favourite creative artists, is also a form of crowdfunding but runs on a membership basis. Anyone can create an account on Patreon selling products and services, and in return they get monetary support directly from their subscribers, aka patrons, on a monthly basis.

Patreon is certainly not the only online channel where individuals can raise funds from the public, but it is one of the most popular platforms for content creators to secure fans’ support directly, with relatively lower service fees and higher content varieties compared to YouTube.

Patreon has changed the nature of fundraising from requiring a link to a particular event or project to a membership base, and the form of support has changed from a donation to a contract. People can choose the tier of support they want, usually starting from US$5. In return for support, activists usually send patrons exclusive letters or notes to thank them.

Since the activists themselves are in custody, their Patreon accounts are usually run by their families, friends or volunteers. The service has also shifted the focus of fundraising from an organisational effort to an individual one. Each activist must compete for support and the number of patrons they attract can vary substantially.

People who took part in last July’s primaries – the focus of the subversion charge against the 47 democrats – are a good example. According to his Patreon page started in August 2020, ex-legislator Au Nok Hin has 180 members. Another former legislator, Ted Hui, has 721 members, but he only joined in December 2020 after leaving Hong Kong. Both men updated regularly, but have vastly different numbers of patrons even though they have similar political backgrounds and joined Patreon at around the same time. Au is now in custody while Hui is in exile.

This raises concerns about how one person’s visibility inevitably leads to invisibility for others. Instead of supporting the opposition as a whole, Patreon arguably magnifies the differences between activists. I have several friends who have said they want to support activists in Hong Kong, but with more and more opening a Patreon account, paying membership fees for every activist can become a big burden.

Beyond such figures as Au and Hui, many less-known activists also use Patreon to raise funds. So while it still seems the most reliable option for Hong Kong activists hoping to raise money, access to funding is far from equal and security is not guaranteed. The risk of being accused of money-laundering may yet await those using the platform, and even before then, the platform itself may self-censor due to political sensitivities.

The high profile of crowdfunding in Hong Kong today belies the many issues that lie beneath the surface.

Francesca Chiu is a PhD candidate focused on urban marginality and spatial politics in Myanmar at the University of East Anglia and the University of Copenhagen. She is a former researcher at the Centre for Civil Society and Governance at the University of Hong Kong. Follow her on Twitter.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.