Hong Kong’s current democracy movement began long ago, in the early 1980s, soon after Beijing’s demand for the city’s return became known. The reformers were a mixed lot, some young, some not. Most were middle-class white-collar types: college students and some faculty; Martin Lee and the lawyers; Szeto Wah and the teachers’ union; journalist Emily Lau; social activist Frederick Fung; labour organiser Lee Cheuk-yan — to name a few.

Others, with memories of China’s recent revolutionary past, were traumatised at the prospect of Hong Kong’s transfer from British back to Chinese rule. The date was to be 1997, when an old 99-year lease on Hong Kong’s northern suburbs expired. The exodus and search for safe havens elsewhere began immediately. Many returned — after they had acquired foreign passports and nationalities for use in case of need.

But some were attracted by the challenge of trying to make their way in a post-colonial era. They were optimistic about the possibilities of a new form of political life, under the rule of a Chinese government that was just then opening up to its own new era of experimentation after the death in 1976 of Mao Zedong.

The aspirations of those days were reflected in Hong Kong’s tradition of commemorating the June 4, 1989 crackdown that ended China’s own 1980s democracy movement. Hong Kong’s new generation of political reformers identified with the occupiers of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Optimists here said they were looking forward to the day when China would be joining Hong Kong rather than the other way around, a day when all might be part of a new democratising era.

This 1980s aspiration lived on in Hong Kong’s annual vigil commemorating June 4. In Hong Kong it became part of the annual ritual on that night. The slogans always included one that especially angered post-1989 Beijing leaders: “End one-party dictatorship.”

The questions then, in the 1980s, were whether a new form of representative local government could be created from scratch, where one had never been allowed to exist before, and whether such a self-governing community could survive within the Chinese state, under Communist Party rule.

The answer now – with Beijing’s promulgation of the National Security Law last summer, and the electoral changes just endorsed by the National People’s Congress — is a resounding no. The two new interventions are even worse than feared, say the 1980s reform movement’s successors. An autonomous democratically elected form of local representative government cannot be created here, at least not in the foreseeable future.

Early days

Beijing was promising that post-1997 Hong Kong would enjoy a high degree of autonomy. So liberal-minded reformers began by arguing that the only guarantee of such autonomy is a strong local government. Without it, Beijing would likely intervene to ensure stability. And the strongest form of government, they said, is one rooted in the people who are being governed, based on direct citizen participation.

There is a specific date associated with this argument. On September 16, 1984, in what was said to be the first time in Hong Kong history, over a thousand people from 89 different groups joined in calling for direct universal suffrage election to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council.

Actually, this was not the first such gathering. But it was the first organised and led solely by Hong Kong Chinese, rather than by a few local British reformers. There had been several past efforts to introduce universal suffrage, even if only in token form. On this occasion, campaigners gathered in a small urban park in Kowloon that would become a nostalgic reminder for the goals of that first Ko Shan Theatre rally.

Beijing initially welcomed the new ideas, but official enthusiasm cooled rapidly as preparations for 1997 began in earnest. The adversarial relationship set in at this time, in the late 1980s, as Beijing took over the drafting of Hong Kong’s new Basic Law constitution for use after 1997. Among Hong Kong’s new pro-democracy reformers, only Martin Lee and Szeto Wah were allowed to join the Basic Law Drafting Committee.

Lobbying efforts nevertheless continued throughout and seemed not to have fallen entirely on deaf ears. When the Basic Law finally appeared in 1990, almost all the reformers’ concerns had been addressed. It promised a high degree of autonomy, universal suffrage elections for both Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and its Legislative Council, and an independent judiciary, plus all the basic rights and freedoms. It was the best that could be expected under the circumstances, said the sceptics.

If only the Hong Kong government, in 2003, had not insisted on activating the Basic Law’s Article 23 mandate for national security legislation, maybe Hong Kong could have proceeded on a gradual course throughout. The reform movement had actually lapsed into a quiescent state during the early post-1997 years, although efforts for a revival were already underway by 2002, when there was even talk of trying to revive the spirit of the Ko Shan Theatre rallies.

The dangers inherent in the Article 23 legislation, promoted during a health crisis similar to the current Covid-19 pandemic, reminded people why they had rallied to demand protections before 1997. At the time, in 2003, epidemics were still treated as state secrets in China, so Hong Kong medical authorities had to work on their own to understand the strange new respiratory disease called SARS that had arrived with cross-border travellers.

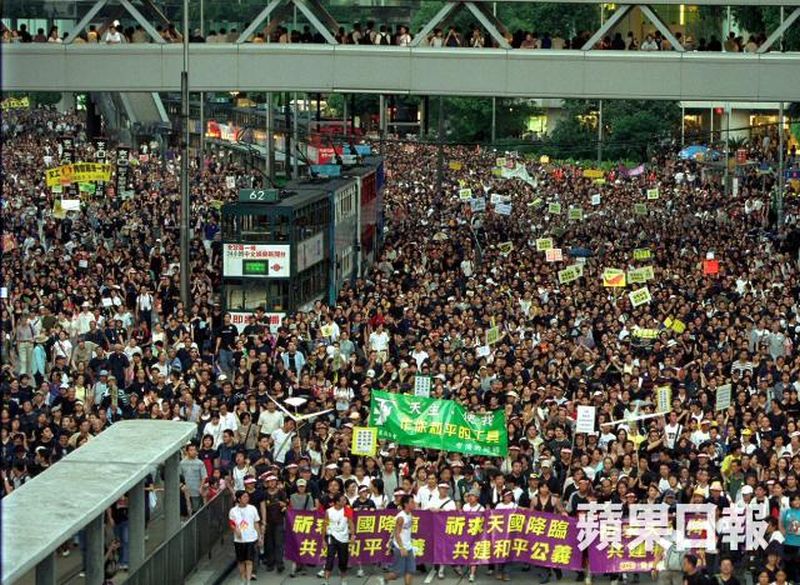

The imminent threat of a security law brought half-a-million people out to march on July 1, 2003. The date marks the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China and marches on that day became another fixture of protest tradition.

Attention has focused ever since on the importance of elections, as a prerequisite for the autonomous self-governing community rooted in the people that could represent their concerns instead of mocking them. The culprits then, in 2003, were promoters from the administration of Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa and especially his Secretary for Security Regina Ip.

Pro-democracy candidates exploited public anger and did much better than expected in the 2003 neighborhood-level District Council election later that year. But the events of 2003 set off alarm bells in Beijing.

The National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) began issuing a series of decisions aimed at tightening control over the Basic Law’s vague words about gradual and orderly progress toward the ultimate aim of universal suffrage elections for Hong Kong’s Chief Executives and for all members of its Legislative Council.

What is universal suffrage?

According to the Basic Law, such reform progress could have begun after 10 years, meaning in 2007. But in the tense post-2003 climate, Beijing issued a decision delaying reforms for another decade. Martin Lee worried that he might not live long enough to see the day.

In due course, however, preparations began for Hong Kong’s first ever universal suffrage Chief Executive Election, to be held in 2017. Beijing had long since announced that the experiment had to begin with the Chief Executive. But preliminary reforms could begin in 2017 for the Legislative Council as well.

Except that after months of officially encouraged community-wide debate, Beijing issued its ultimatum on August 31, 2014. The 8.31 decision totally ignored the general agreement that had emerged during the debates for some form of democratic nomination to precede the actual one-person, one-vote universal suffrage election itself. Also ignored were any preliminary changes, at the Legislative Council level.

According to Beijing’s 8.31 decision, the 2017 Chief Executive candidates must not only be approved by Beijing but must first be endorsed by Hong Kong’s existing Chief Executive Election Committee. This 1,200-member body – tasked with anointing Beijing’s choice for Chief Executives — is itself designed in such a way as to guarantee success for Beijing’s preferences.

It was this decision that sparked the 79-day Occupy Movement street blockades which began in late September, 2014. Pro-democracy legislators then held together and refused to give the necessary endorsement that was also required.

But Beijing also refused to budge. And only at this point, in 2015 just ahead of the Legislative Council vote, did officials finally reveal what they had not admitted throughout the months-long consultation and debates: their 8.31 decision was what Beijing meant — and all that it would ever mean — by “universal suffrage” elections for Chief Executive. The “gradual and orderly” progress had reached its end result.

Instead of the “genuine” universal suffrage elections they had hoped to achieve, Hong Kongers were to be allowed only a mainland-style election that was itself the end result of China’s own abortive pre-1989 reform experiments. In the event, local party officials designate candidates and everyone can come out to endorse the party’s choice.

Hong Kong’s election cycle then proceeded in the existing unreformed way. But pro-democracy candidates including some young activists from the Occupy Movement did better than expected in the 2015 District Council elections. The pattern repeated itself in the 2016 Legislative Council election, and then Beijing’s reaction set in.

A new decision on oath-taking was issued, ultimately removing six legislative councillors for not taking their oaths of office properly during the October 2016 swearing-in. The judicial review challenges and special elections to replace the six dragged on for three years from one futile attempt after another to reverse the disqualification decisions.

From Beijing’s perspective, an ominous new trend had emerged within Hong Kong’s democracy movement. It was officially denounced as separatism or independence and was at that time only attributed to a few who had allegedly misunderstood Beijing’s original promises about a “high degree of autonomy.”

But as resentment grew so did the demands it reflected, until now under the new national security regime everyone resisting the mandates from on high is being tarred wth the same brush.

The new themes calling for “genuine” autonomy did not begin to leave much of a mark until the second decade of the new century — as local frustrations grew over restrictions like the delayed electoral reforms and the growing mainland presence here. Such ideas naturally took hold first, although not exclusively, among the younger generation and fuelled their growing defiance after the failure of the 2014-15 campaign for universal suffrage Chief Executive elections.

The changing mood was signified by dropouts from the annual June 4 vigils. Those boycotting the event aimed to draw a clear line between their local concerns and those of Hong Kong’s traditional democracy movement — with its annual call for the downfall of one-party rule that still signified the ideal of a new democratic China.

Beijing might have welcomed the split between new localists and Hong Kong’s mainstream pan-democrats. According to the new line of thought, Hongkongers should concentrate on creating the kind of society they wanted for Hong Kong. What happened in 1989 was long ago and Tiananmen was a mainland affair that had nothing to do with them.

Instead, Beijing denounced the split for what it also was, namely, a new threat to Communist Party rule over all Chinese territory. And Beijing could also see the new localist trend was catching on. The public was listening and so were mainstream pan-democrats.

Without defining it very carefully, all the main pro-democracy parties included the aim of “self-determination” in their campaign pledges ahead of the 2016 Legislative Council election. It was why so many tried to improvise by putting a defiant localist slant on the oaths they took during the October 2016 swearing-in ceremony.

And it was into this combustible mix that self-declared political innocent Chief Executive Carrie Lam threw her 2019 extradition bill, igniting Hong Kong’s six-month season of street protests. Still, decision-makers in Beijing might have been content to order a law-enforcement crackdown and let the police handle it — but for what also occurred in 2019.

The November District Council elections produced an unprecedented landslide victory for pro-democracy candidates. But more than the victory itself, candidates had for once joined together in a common platform declaring their support for the disruptive street protests then at their height with the occupation of two university campuses.

And among the protesters’ “five demands, not one less,” was the old ideal that has now evolved into a demand for genuine universal suffrage elections to distinguish them from their mainland-style party-controlled counterparts.

An electoral system for the national security era

Beijing officials have now made their decisions and are designing solutions aimed at solving all their Hong Kong problems in one sweeping political rectification drive. By its standards, Hongkongers would probably have been better off accepting the 2003 national security legislation and Beijing’s August 31, 2014 political reform directive.

Here and now, as with the events of 2003, those of 2019 only reinforced Beijing’s determination to impose its will. The basic decisions were made at the Fourth Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Central Committee that met in late October 2019. The new National Security Law was promulgated on June 30, 2020. And nails are currently being driven into what Beijing hopes will be the coffin of Hong Kong’s aspirations for Western-style universal suffrage elections.

Already, Hong Kong’s introduction to the new national security regime is reproducing scenes from another era — like watching a movie or reading a novel — “1984” being played out in real time.

By now, all the leading pro-democracy candidates, who were preparing to contest the Legislative Council election originally scheduled for September 2020, have been arrested for subversion under the new law.

Court proceedings are underway in a chaotic mix of common law conventions and mainland-style rules. Hong Kong’s bewigged judges, still in their British courtroom attire, strain to produce coherent rulings even on the straightforward matter of whether or not to grant bail.

The 2020 Legislative Council election, initially delayed for a year on the grounds of the pandemic, seems set for a further delay, tentatively until December this year. Officials now admit the extra time is needed for the legislative formalities that will be played out in Beijing to amend the Basic Law. Its Annexes One and Two spell out the original methods for selecting Hong Kong’s Chief Executives and forming its Legislative Council.

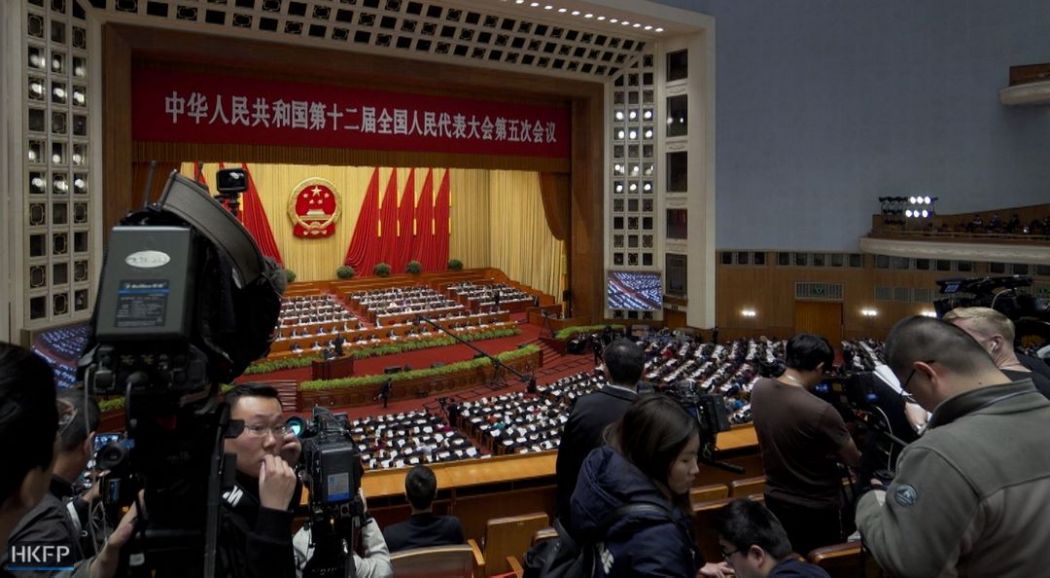

The just-ended annual meetings of the National People Congress endorsed the rationale and general principles for the reform project. In due course, the NPC Standing Committee will issue decisions spelling out the details. But according to the advance publicity, Hong Kong’s electoral system is to be completely revamped.

The aim is to ensure that only “patriots” rule Hong Kong. Exact criteria defining patriotism remain to be specified. But they will apply to all those who occupy authoritative positions in government, including the seats in the Legislative Council. The changes are being designed, say their promoters, to ensure that only such people can contest elections.

More specifically, the aim is to guarantee that no local political leaders like the current class of pro-democracy politicians can ever again aspire to win a Legislative Council majority, or influence the selection of Chief Executive. They had hoped to do both during the current election cycle. And the charge of subversion against all the candidates rests on their campaign pledges to try and do just that.

The procedures for the selection of the next Chief Executive are still scheduled for later this year and early next. But before then, Beijing plans to have designed and introduced the necessary changes ahead of the next Legislative Council election, now tentatively rescheduled for December this year.

The old Election Committee will become the centerpiece of the new revamped system. In recent years, pro-democracy activists gave up trying to reform this committee because of its ungainly convoluted design. They said it conjured up images of the “rotten boroughs” that were a target of Britain’s Reform Act in 1832.

The committee, as of now before its planned redesign, features carefully-crafted sectors and sub-sectors that comprise four main occupational categories, each with 300 members: business; white collar professions; labour unions, welfare, and sports; and government institutions. This last includes all of Hong Kong’s delegates to the National People’s Congress, plus all members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council and of the 18 District Councils.

In 2016 the 1,200 members of this committee were elected by some 246,440 variously designated voters from the sub-sectors of the four main categories. The sub-sectors also provide the voter base for the Legislative Council’s Functional Constituencies.

The Election Committee itself is currently used to endorse Beijing’s’ choice for Hong Kong’s Chief Executives. It also endorses the officially approved members of Hong Kong’s National People’s Congress delegation.

According to current plans, the Legislative Council will be expanded from 70 seats to 90, and the Election Committee from 1,200 members to 1,500. The 20 new Legislative Council seats will be filled by the Election Committee, details yet to be revealed, that is whether by the committee as a whole or by the committee’s Functional Constituency voters. In any event, this body of people will be responsible for filling the council’s largest bloc of seats, that is, 50 of the new 90 total.

The Election committee’s 300 new members, comprising its fifth sector, will be tapped from among local pro-Beijing loyalists.

The current composition of Hong Kong’s 70-seat Legislative Council is 40 Geographic Constituency legislators elected directly by voters, albeit according to a proportional representation system. The other 30 legislators are elected by the Functional Constituency voters.

Additionally, there is to be a vetting committee, possibly created from among members of the Election Committee. Prospective candidates in future Legislative Council elections must first be properly vetted and certified for their patriotic credentials.

Promoters of this change say the current practice of tapping civil servants to act as vetting officers is not a properly authoritative means of certifying the credentials of prospective candidates. There is also a proposal for the new vetting committee to maintain scrutiny of legislators’ performance throughout their tenure.

For the 40 popularly elected Geographic Constituency legislators, voting districts and methods are to be redesigned so as to reduce the chances of success for pro-democracy candidates, despite voter preferences.

Voters have consistently given pro-democracy candidates more than half the ballots cast in every election where the two sides have been in direct competition. Democrats’ city-wide 2019 sweep of the District Councils — the only directly elected one-person, one-vote bodies in Hong Kong — is a lesson the system’s re-designers have taken to heart. The 177 District Council seats on the Election Committee are likely to be filled by others.

Where to from here?

The looming question now is whether the democracy movement can survive the frontal assault. Partisans have so far managed to overcome every setback and emerge stronger than ever after every defeat. But for now, while the new national security regime is still in the making, questions inevitably turn to the past.

Would aspirations have been better served by accepting the 2003 national security legislation and Beijing’s August 31, 2014 political reform directive? For sure, the lives of Hong Kong’s front-line democracy activists, now sitting it out in detention, would have been much easier. But probably, the end result for their aspirations would have been much the same.

Beijing officials like to cite the authority of the late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to explain and justify their current decisions. Especially useful in this respect was his statement made during the Basic Law drafting process in the late 1980s — about patriots being the main force running Hong Kong’s new post-1997 “one-country, two systems” governing arrangements.

Martin Lee, who was a member of the Drafting Committee, has often said that if Deng were alive today, he would never approve of the current hardline approach. Lee is no doubt deliberately overlooking other things Deng Xiaoping also said at that time.

During the meeting with Basic Law drafters on April 16, 1987, Deng offered a clear-eyed distinction between Western democratic governing traditions and those of his own party. He distinguished between socialist and bourgeois democracy. Western countries, he said, have separation of the three powers and multi-party elections. China didn’t have such elections and the executive, legislative, and judicial branches were not separated.

He went on to discuss the possibility of multi-party elections for post-1997 Hong Kong and said they were not a good idea. “Hong Kong’s administrators should be the people of Hong Kong who love the motherland and Hong Kong, but will a general election necessarily bring out people like that?” He had his doubts. Then as now, loving the motherland signifies what Beijing officials mean by patriotism, which signifies in turn the acceptance of Communist Party rule.

But as for the current generation of decision-makers in Beijing, their old-style hardline drive to try and force Hong Kongers to love the motherland will probably create more problems than it can solve — especially since Hong Kong’s democracy movement has somehow managed to revive and grow after every setback.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.