“This is the BBC.” That sign-off to a short piece on the Newshour programme, broadcast on WNYC radio in the United States in late summer 2005, changed the course of my photographic career.

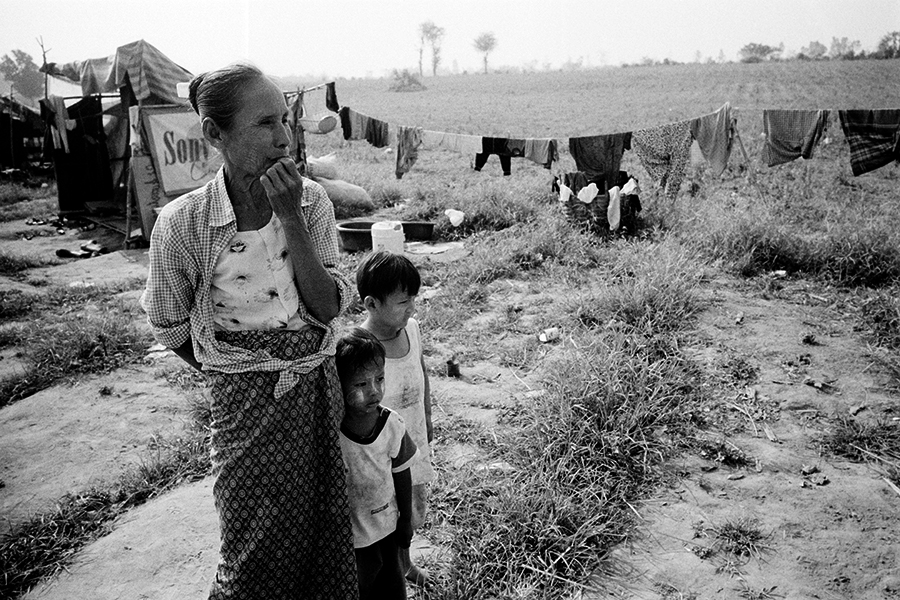

The story I heard that day was about Dr. Cynthia Maung, a refugee from Burma, and the clinic she runs in the town of Mae Sot on the border between Thailand and Myanmar to care for the Karen people and other refugees who had fled fighting and oppression in their home country. The story so engrossed me that I immediately set out to contact the clinic about a possible visit, to document what was going on there.

I did not know much about Myanmar, the situation that the Karen faced, or the full picture of what was happening there. But being the son of a doctor and a nurse, I’ve always been intrigued by stories of doctors who strive against great odds to help others.

So after trading e-mails with the clinic, I bought a plane ticket, took a month’s leave from my day job and in February 2006 set off for Asia for the first time.

I knew no one apart from the faceless person at the clinic I had e-mailed, did not speak Thai, Burmese, or Karen, and did not fully grasp what I was getting into. It was an immersive learning experience, one whose lessons I have never forgotten. I have also never forgotten the people I met, and the stories of the Karen people and of Myanmar in general. I still closely follow the news from the country, good and bad.

It has now been 15 years since I made that trip and I am older, somewhat wiser and definitely greyer. But the situation on the ground has not changed.

Aung San Suu Kyi is once again under house arrest with a military junta again running Myanmar. The Karen who hoped that a peace deal with the government was on the horizon in 2006 are no nearer one now.

In Thailand in 2006 a military coup overthrew the elected government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The political repercussions continue today, with mass protests against the military and against the new king again bringing crowds onto the streets.

Through all of this, journalists are once again caught in the middle as they attempt to do their jobs.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, since February 11 at least six journalists have been detained in Myanmar. The junta has also proposed a new law that would force internet providers to remove or prevent the publication of content deemed to “cause hatred, destroy unity and tranquility” or that is “untruthful news or rumours,” according to Reuters. It has blocked Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, and internet outages have been frequent.

All this stifles the work of journalists and impedes press freedom, but also affects free speech by the people and their ability to share information about what is going on in their county. At least three protesters have been killed and the clampdown is likely to intensify.

Thailand, which is still in the throes of its own protests, has also seen press freedom and free speech eroded. Even before the protests broke out, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha declared a state of emergency and issued an emergency decree that allowed authorities to order journalists and media companies to “correct” reports that the government deemed incorrect.

It also allowed the government to pursue charges against journalists for “reporting or spreading of information regarding Covid-19 which is untrue and may cause public fear, as well as deliberate distortion of information which causes misunderstanding and hence affects peace and order or public morals.” All this allows the government to censor journalists for reporting news that authorities do not agree with under the guise of national security.

The increased use of lèse-majesté laws to silence the opposition has also raised alarm at the United Nations and elsewhere.

Then there is the BBC itself. China has banned it from broadcasting within the country, and Hong Kong’s broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong has quickly followed suit. This comes after the British revoked the broadcasting license for the China Global Television Network in the UK, citing its control by the Chinese Communist Party. China’s National Radio and Television Administration said the BBC’s reporting “seriously” violated its broadcasting guidelines by not being “truthful and fair,” adding that it harmed China’s national interests and “infringed the principles of truthfulness and impartiality in journalism.”

The BBC said it reported from around the world “fairly, impartially and without fear or favour.” It had previously reported on Covid-19 in China, as well as the persecution of the Uighur ethnic minority and the internment camps in which they have been held.

While the press visa war between China and the United States and various other countries continues, this move seems like the next volley. It not only stops journalists from doing their work, but prevents their outlets from broadcasting. The fact that Hong Kong, where press freedom is enshrined in the Basic Law, was so quick to follow suit shows how strong Beijing’s influence has become since the implementation of the National Security Law last year.

As China further cracks down on the press, other countries in the region are taking note. Cambodia has even created its own version of China’s Great Firewall to curb online dissent.

Press freedom is attacked and free speech curtailed around Asia at a time when news from the region is of global importance. It can affect everything from international trade agreements, to the availability of raw materials to keep the world’s factories running, to the price of agricultural products. Collectively the news can drive stock markets around the world up or down. More importantly, it can call for help for the oppressed, the overlooked, and those whom the majority would try to erase.

With President Biden now in office in Washington, the UK again on its own, and Europe facing its own changing of the guard in terms of leadership, the question now is which world powers are willing to use their economic influence to try to affect social issues. The answer to this question will have long-ranging effects on both oppressed people and the free press worldwide.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.