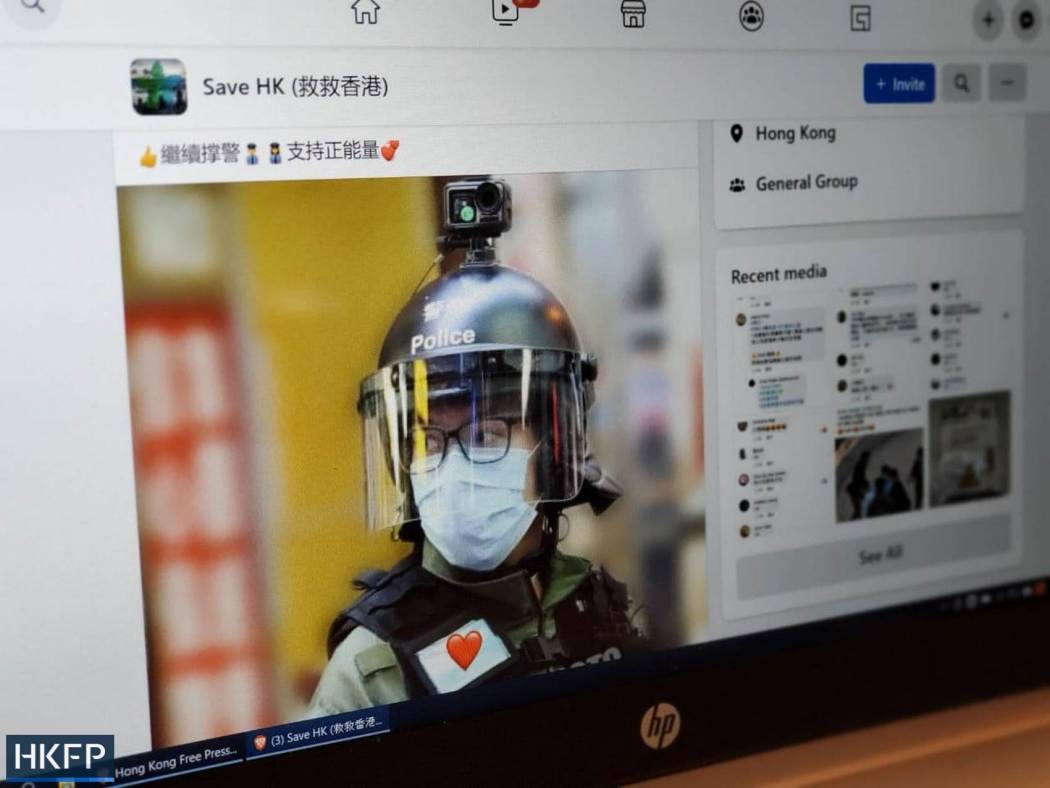

A pro-government Facebook group – which was the biggest in Hong Kong before being abruptly shut down by the social media platform last December – has bounced back after launching a new group and regaining many of its followers.

SaveHK is run by Adrian Ho, the nephew of former Macau Chief Executive Edmund Ho Hau-wah.

The group calls itself a “blue camp group for those who love the country and love Hong Kong, to save Hong Kong using positive energy.” It boasted at one point close to 200,000 members. Within days after being shut down, a new group was created which grew to 110,000 followers.

By comparison, dozens of other pro-establishment groups count membership in the tens of thousands each. Two district-based groups intended for “yellow” or anti-government users had around 100,000 to 120,000 members.

Users of SaveHK actively discuss current events and share news, memes, photos, and videos, on topics ranging from the protests of 2019, Covid-19 and Chinese and international politics. Some followers even share their distress about family members with opposing political views. More often than not, users will voice support for government decisions and police actions, attracting thousands of “likes” and hundreds of comments.

Sometimes members will question government policies in what they call a constructive spirit, or wonder why the chief executive is not more forceful in implementing her plans.

SaveHK members are united on one thing: their firm and intense dislike of protesters calling for democracy, opposition politicians, and any overseas politicians who sympathise with them. They share videos of protesters committing violence and cartoons vilifying politicians. Occasionally, members swap social media posts by civil servants demonstrating sympathy with the protests or criticising the government, and call on others to report them to the authorities.

SaveHK’s vibrant and engaged discussions are punctuated by its administrator’s measured and courteous interventions. Apart from sending greetings and encouraging members to remain united, Ho will also remind them to avoid using abusive language in order to forestall Facebook censorship.

HKFP found that Adrian Ho, whose Chinese name is Ho King-hong, had shared in company records a home address with his father Ho Hao-veng, elder brother of former Macau Chief Executive Edmund Ho. Edmund Ho is currently vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a top mainland advisory body, and appeared next to Adrian Ho and his wife in a wedding video on YouTube, which has now been taken down.

Speaking in fluent English and dressed in a sharp suit, Adrian Ho told HKFP that, although he spent his formative years in the UK and the US, his family has played “an integral part” in shaping all of his personal values, and his identity as a Chinese person.

After attending La Salle Primary School in Hong Kong, Ho – then aged 13 – went to Repton, a British boarding school. He graduated from Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania in the US. He worked in investment banking after returning to Hong Kong and currently runs an investment business on clean energy in China’s Xinjiang region.

Although four of Ho’s cousins are members of various People’s Political Consultative Conference committees and one is a Macau representative at the National People’s Congress, Ho said he had not been politically active before the birth of SaveHK and was now “playing catch-up” compared to his relatives’ contributions to Macau and Hong Kong.

“I want to keep this information outside of the group, so when people talk about SaveHK, people talk about what we do, what we bring to Hong Kong, and not who’s behind SaveHK,” he told HKFP.

A safe haven

The urge to create SaveHK came in mid-2019, when massive and often violent protests broke out in Hong Kong’s streets every week. News and social media was “very much one-sided,” Ho said. “Cyberbullying became a fashionable thing to do for the opposite camp.”

“Anybody who tried to express a different opinion than them, on the internet, would be attacked and judged, immensely,” he said. “When there was a group called SaveHK that provided them with this opportunity, I think a lot of people signed on to that.”

Anti-government protesters had called for efforts to infiltrate SaveHK to stir up confusion and discord in the community by using fake accounts. Posts by government supporters were sometimes screenshotted and mocked on other platforms. In order to keep the group “a safe haven for rational, like-minded people to express freely” without being attacked or judged, SaveHK users would report members deemed to be “yellow” and Ho would promptly remove them.

As the group grew, the SaveHK community attracted other pro-government allies. Ho partnered with other YouTube influencers who produce political commentary and appeared as guest in their videos. He interviewed and attended events with New People’s Party leader Regina Ip and politician Dominic Lee.

Using the same production company as its new-found YouTube allies, SaveHK also produced music videos, hosted live online charity concerts, and made short parody films poking fun at those Ho would describe as the “anti-establishment.” Ho often took the stage to sing and even acted in one film, playing a cunning rich man luring people to join protests in a video game.

“We strive to fight against fake news, incorrect information, and a skewed and biased political narrative in Hong Kong,” Ho said, pointing to conspiracy theories about murders allegedly committed by police against protesters. “We would set the record straight, whenever there is biased opinion, one-sided opinion, on for example police brutality.”

Ho said he believed the police use of force during the protests was necessary to maintain law and order, instead of unreasonable and excessive as the opposition insisted. Users in SaveHK regularly cheered police actions, and sometimes may swoon over photos of good-looking officers.

Speaking on the narrative that SaveHK wanted to put out, Ho was careful in his choice of words. “I don’t want to go too deep on police stuff,” he told HKFP.

SaveHK would be a place where people can speak their minds, point out inaccuracies and falsehoods promoted by the opposition, and “to make sure that… the righteous voice, the correct voice, is heard out there, instead of everything anti-establishment,” Ho said.

Then came the national security law imposed directly by Beijing just before midnight on June 30 last year. It criminalised subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts, which were broadly defined to include disruption to public transport and other infrastructure.

On July 1, protests against the new law broke out in Wan Chai and Causeway Bay, with 370 people arrested. Police displayed purple flags warning protesters that their slogans, signs, and behaviour could breach the new law. In subsequent days, the government singled out the slogan “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,” which came to defined the protests, and described it as secessionist.

“Yellow” businesses and eateries took down their pro-democracy message boards, several apps offering “yellow” business catalogues stopped working, and some pro-democracy books were pulled from public libraries.

To SaveHK members, the law was an overdue blessing in restoring order. “They felt very frustrated, until the national security law — they started to be able to take a couple of deep breaths, and rejoice over what it would bring to the stability of Hong Kong,” Ho said.

But on December 6 last year, three days after pro-democracy newspaper founder Jimmy Lai was remanded in custody on suspicion of committing fraud, and one day after former Democratic Party lawmaker Ted Hui fled Hong Kong for Europe, Facebook told Ho that SaveHK would be removed. It said the group had violated its rules on “regulated goods,” which referred to content promoting the sale or exchange of items such as firearms, drugs, alcohol, or live animals.

The group of 200,000 along with all its content vanished within minutes. The same day, a “yellow” group for Tai Po district with 120,000 members was also removed, for violating the platform’s rules on hate speech.

Censored by Facebook

“If it’s legitimate, meaning that if someone has violated community standards, whether it’s hate speech or discrimination, I can accept that,” Ho said. Facebook had always censored some of the group’s content due to abusive language, but he said there was no formal notice of removal, apart from one that quickly disappeared along with the group, without any possibility of appeal.

Rejecting the group’s involvement with “regulated goods”, Ho said the social media’s platform’s decision was “truly not legitimate.”

The pro-establishment camp saw the shutdown as an attempt by Facebook to silence them. As soon as Ho started a new group with an identical name, Hong Kong’s largest pro-government political parties and politicians called on followers to join SaveHK again.

In retrospect, because a “yellow” and a “blue” group were both removed on the same day, Ho said he tended to believe Facebook was trying to appear politically neutral. But “if censorship was necessary for silencing or eliminating political believers, then it’s complete horseshit,” he added. Since then, Ho has become “extremely careful” about moderating content in order to avoid crossing the line drawn by Facebook.

Ho said he believes in freedom of speech, but “there is a bottom line.” Free speech, he said, is not a free pass for breaking the law.

“I think people are absolutely confused [believing] that they are not allowed to criticise the government. Everybody criticises the government right now – look at the internet,” he said.

But the national security law should hold people accountable for verbal and physical acts. “If you don’t respect ‘One country, Two systems’, and if you try to overthrow the government, then you have to answer for your crimes.”

Three days after SaveHK made its comeback and about 80,000 of its members had re-joined, Ho addressed them as group administrator: “I believe the group’s removal was a blow to me and to everyone here, because it had so many memories, blood and tears, that got us through tough times […] It is a blessing that we could start again, a new group with the same beliefs, but with a bit more appreciation and attachment,” he wrote.

“As said in English: What doesn’t kill you will make you stronger, that is our Save Hong Kong spirit.” The post received over 18,000 likes and 3,000 comments in support.

“I’ve always believed that pro establishment camp voices were the majority, this whole time,” Ho said. “60 pro, 40 anti establishment, it’s always been that.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.