By Maggie Holmes

One of the biggest challenges faced by children from non-Chinese speaking families who study in local schools is the absence of Jyutping (Cantonese romanisation) in their Chinese- language textbooks and other study materials.

The government provides HK$200 million in annual funding for schools to implement the “Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework.” However the Education Bureau has no requirement that core teaching materials created for the scheme include Jyutping.

Without Jyutping, students will not be able to learn Chinese effectively and the money will be wasted.

Written Chinese is largely non-phonetic, so Jyutping is a quick and accurate way of showing how a character is pronounced. Without this clarity, it’s extremely difficult for students to memorise the thousands of Chinese characters required by the local school curriculum.

Jyutping helps children learn new vocabulary more quickly, before they know the Chinese characters. It also provides a convenient way to input Chinese characters into digital devices.

Jyutping also has an interesting role to play in the teaching of spoken Cantonese. While many teachers are reluctant to use non-standard Cantonese characters in a classroom setting, they may be more willing to use Jyutping to write Cantonese words and phrases.

Research by Hong Kong academics shows a clear association between the early use of Mandarin Pinyin and the development of Chinese reading skills.

Romanisation strengthens a child’s “phonological awareness,” an understanding of a language’s sound system which is a predictor of literacy skills. Pinyin also allows children to read materials which use Chinese characters that they have not already studied.

It is reasonable to assume the same positive effect for Cantonese romanisation. Yet the Education Bureau does not require, or even recommend, the use of Jyutping on classroom resources in Hong Kong and it’s hard to get a true picture of how many schools use it.

Some schools, usually those with a higher concentration of non-Chinese students, do use Jyutping and go to great lengths to make Chinese learning accessible to children from all linguistic backgrounds. Still, too many students are left struggling through textbooks which have essentially been created for native Chinese speakers and do not include a phonetic aid.

Learning Chinese as an additional language without romanisation is unthinkable outside of Hong Kong.

In other parts of Asia that use Chinese characters, even native speakers learn a standard phonetic form in early childhood.

Mainland China teaches Hanyu Pinyin in Primary One, Taiwan uses the Bopomofo system and in Japan, books for young children are written entirely in Hiragana, which is also placed alongside or above the Kanji (Chinese characters) in materials for older children.

Hong Kong makes some use of romanisation but students of Cantonese must navigate a mish-mash of different systems, some of which date back to the work of 19th Century missionaries.

Place names and personal names are transliterated using the government’s unpublished and unfathomable system of romanisation. Adult learners of Cantonese switch between “Sidney Lau”, “Yale” and “Jyutping”, according to the preference of their teaching institution or textbook publisher.

Jyutping, developed by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong in 1993, is the most recent form of romanisation and is our best hope for a Hong Kong standard form of romanisation in the future.

So why are children in Hong Kong not taught Jyutping?

The most commonly cited reason for not using Cantonese romanisation is that children rely on the Jyutping and do not learn to read the characters.

In fact, the problem is not with romanisation per se so much as the way it is used. Too often, romanisation is placed above every Chinese character in a piece of text. For students whose first language is alphabetic, the eye is inextricably drawn to the romanised form, at the expense of reading the Chinese character.

To make matters worse, some schools use textbooks with Mandarin Pinyin written above the text, in classes where Chinese is being taught in Cantonese. This is most unhelpful, especially for children from non-Chinese speaking families.

Romanisation should not be used in this way. Instead, the target vocabulary for a piece of text should be listed separately, with romanisation (and preferably English or other home language) written adjacent.

Some teachers are understandably concerned that mastering Jyutping is too big a burden for children, who are learning Chinese and even English from scratch.

However, many teachers already write an approximation of Cantonese pronunciation, based on their knowledge of English, on homework materials. Students and even parents scribble their own self-invented versions of Cantonese sounds onto the textbook.

Unfortunately, these ad hoc attempts at romanisation do not help the child develop an accurate understanding of the Cantonese sound system, upon which they can build. It would be much better for all students to begin learning Jyutping in the early years and use it methodically throughout their school life.

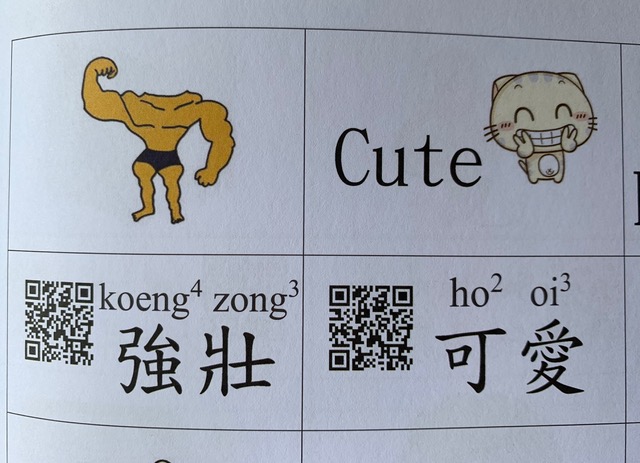

Even an incomplete knowledge of Jyutping can help jog the child’s memory of how a character is pronounced, whilst instantly making the language more accessible to parents who are not literate in Chinese. In the early years, the provision of audio, either via QR code or digi-pen, can be used to clarify pronunciation until parent and child get to grips with Jyutping.

Jyutping is an indispensable tool for the teaching of Chinese as an additional language in Hong Kong, so its inclusion in core study materials should not be left to the whims of individual schools.

The Education Bureau must integrate Jyutping into the Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework, require its usage on CSL textbooks and provide Jyutping training for teachers.

Without Jyutping, children from non-Chinese speaking families cannot learn Chinese effectively and no amount of government funding will bring about a substantial improvement.

Maggie Holmes is co-founder of Chinese as an Additional Language Hong Kong, an organisation which supports students studying Chinese in Hong Kong.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.