By Senia Ng

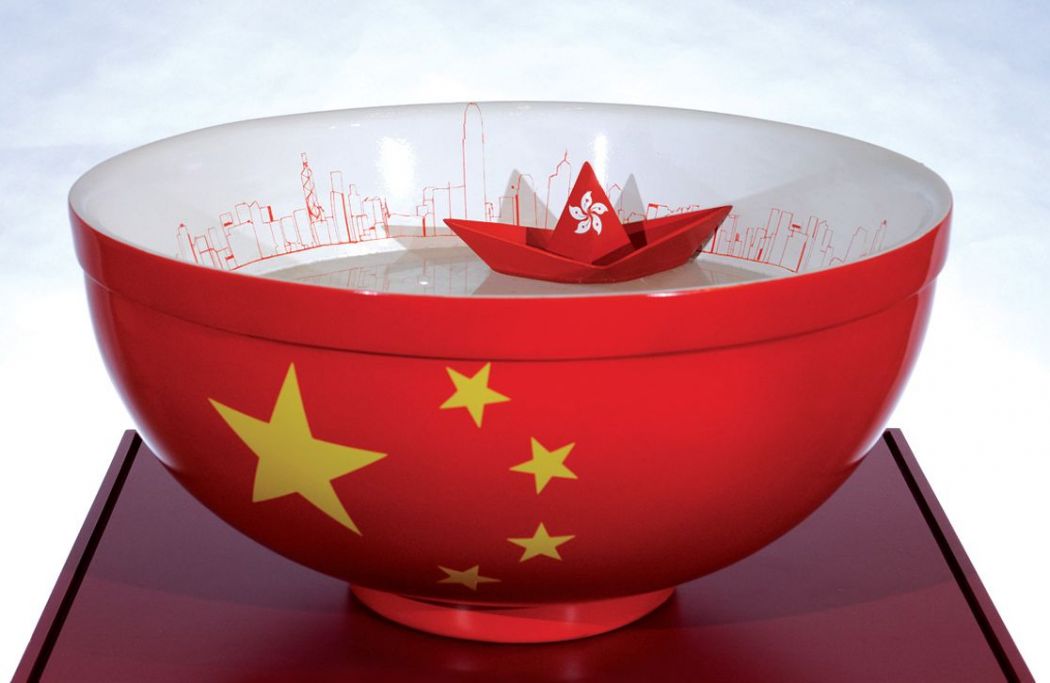

The National Security Law is a distinctive legal regime which runs in parallel with, and if necessary over-rides, the existing legal system in Hong Kong.

This was the conclusion of the Court of Final Appeal (CFA), which handed down its judgment in respect of Mr. Jimmy Lai’s case concerning bail on February 9, allowing the appeal of the Department of Justice.

The CFA held that the courts of Hong Kong have no jurisdiction to review the NSL for compatibility with the Basic Law, since the NSL was enacted in accordance with the provisions of the Basic Law and the procedure in that law’s Article 18.

The provision allows for the addition of Mainland laws concerning defence, foreign affairs and other matters outside the limits of HKSAR’s autonomy into Annex III of the Basic Law, which then take effect by way of legislation or promulgation.

The CFA confirmed that the NSL, which safeguards national security, involves matters outside the limits of HKSAR’s autonomy. This was despite the fact that Article 23 of the Basic Law provides that the HKSAR shall enact laws on its own to safeguard national security.

This indicates that even where express powers have been given to the HKSAR, that does not mean the matter covered falls exclusively under the HKSAR’s autonomy. This appears to leave any power that has been given to the HKSAR vulnerable to the same argument, so it is hard to say where the line demarcating the division of powers between the HKSAR and the Central Authorities now lies.

The confirmation of the validity of the NSL, which took effect in Hong Kong by way of promulgation, as opposed to legislation, further implies that laws enacted by the socialist legal system of Mainland China can be directly applied in Hong Kong, even where the matters covered are substantive in nature.

In the past, promulgation was only used for mainland laws which were relatively technical in nature. Where substantive issues were at stake, e.g. where regard had to be given to impact of the law on human rights protections in Hong Kong, legislation would be used.

The issue of bail

Lying at the heart of the challenge was the issue of bail. The CFA held that the regime for bail under the NSL is different from that provided for in the existing criminal laws of Hong Kong.

Under the existing regime, there is a presumption in favour of bail. Bail should be granted unless there is a risk that the accused will abscond, commit further offences while on bail, interfere with a witness or pervert or obstruct the course of justice.

However, under Article 42 (2) of the NSL, there is a presumption against bail: bail should not be granted unless the judge has sufficient grounds to believe that the accused will not commit acts endangering national security whilst on bail.

This does not mean that once the court is satisfied that the accused will not commit acts endangering national security while on bail, he will be granted bail under the NSL regime. The CFA held that the court will then need to consider whether the risks provided for under the existing regime exist, and if so, must still refuse bail.

This means that even though an accused charged under the NSL cannot benefit from the presumption in favour of bail under the existing regime, he will still have to meet the conditions which the existing regime requires.

Human rights protections

Given that the courts of Hong Kong have no jurisdiction to review the NSL for compatibility with the Basic Law, a person cannot challenge an NSL provision on the basis that it violates the human rights and fundamental freedoms protected under the Basic Law and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance (Cap. 383).

The CFA emphasised that pursuant to Article 4 of the NSL, human rights and fundamental freedoms are to be respected and protected while safeguarding national security in Hong Kong.

However, the CFA refused to give protection when Mr Lai argued that, in line with international human rights jurisprudence, the placing of a burden of proof upon him to secure bail amounted to a restriction on the right to liberty.

The CFA stated the cases raised were irrelevant as they rested on a presumption in favour of bail, which had been expressly displaced by Article 42 (2) of the NSL. It is therefore clear that, even if a provision of the NSL appears to threaten human rights and fundamental freedoms, it will still be upheld by the courts.

Taking into account extrinsic materials

The tradition in Hong Kong courts is that when considering the meaning of a statute the court will look primarily at the wording of the statute. Other sources external to the law itself, like policy documents or the utterances of politicians about the purposes of the law, are “extrinsic” and excluded unless the wording of the statute was unclear.”

However the CFA departed from this established legal principle and opened the doors for the consideration of extrinsic materials for construing the meaning of the NSL. In this case, the CFA took into account extrinsic materials simply on the basis of the special status of the NSL.

Construing the meaning of law with reference to extrinsic materials is problematic because extrinsic materials may contain political statements, or be political statements in and of themselves.

In this case, the CFA took into account the Explanations presented by the Vice Chairman of the NPCSC on the draft decision on NPC leading to the promulgation of the NSL, which set out the political events and protests that occurred in Hong Kong since 2019, with emphasis on the disapproval of protestors’ acts and opinions.

The court set no limit to the extrinsic materials which might be considered in NSL cases. It can include future documents made by the NPC, NPCSC or any other institution, which may purport to set out the legislative intent of the NSL. This gives rise to the danger of moving goalposts, and allows changes in the meaning of the NSL as situations arise.

Rule of law

Lying at the heart of Hong Kong’s legal system is the principle of rule of law, which is supposed to be protected by specific mention in Article 5 of the NSL.

However, it appears that the principles of legal certainty and protection of fundamental rights which are central to the rule of law have been undermined by the NSL. Instead of bringing stability, the NSL has shaken up the legal system in Hong Kong, with its now proven ability to trump not only domestic legislation and the common law, but even human rights protections and Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

Senia Ng is Barrister in Hong Kong specialising in human rights and constitutional law. She is also a Member of the Democratic Party of Hong Kong.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.