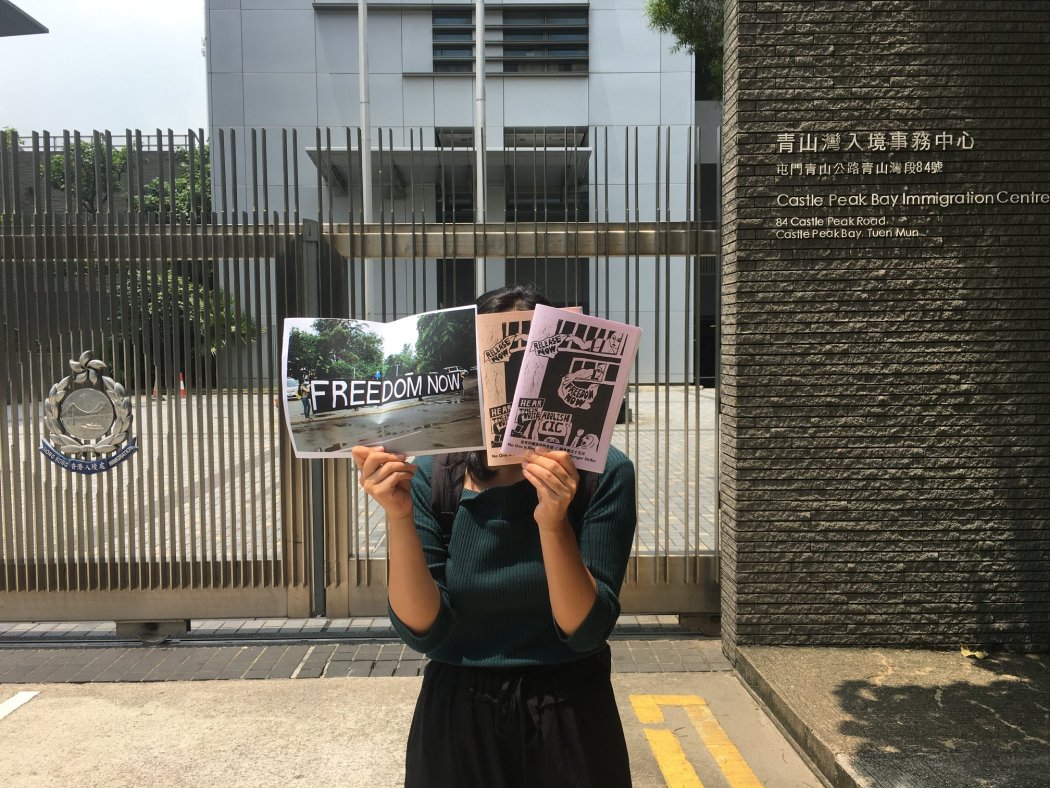

Recently, Ahmed Sani Salman, a Pakistani asylum-seeker held at the Castle Peak Bay Immigration Centre (CIC) for eight months, appeared in court to contest his arbitrary and indefinite detention by the Immigration Department. Salman has been on a hunger strike for over 160 days. In court and in his open letter, Salman said he was abused by CIC staff and denied medication prescribed by the hospital. He was not the first detainee to allege inhumane treatment and indefinite detention at CIC.

For years, detainees and their advocates have been reporting human rights violations inside the facility. Many detainees were asylum-seekers fleeing persecution in their home countries. They reported that they were being arrested and indefinitely detained at CIC without a clear explanation. They also alleged humiliating treatment and mental and physical abuse by staff there.

The investigative journalist team of RTHK’s Hong Kong Connection recently revealed that some detainees are held naked in empty rooms for up to 24 hours, wearing only an adult diaper.

While CIC is closed to the public and the media, former pro-democracy lawmakers Eddie Chu Hoi-dick, Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung and Shiu Ka-chun had previously made official visits to the facility. They all attested to very poor living conditions there. Despite serious claims from detainees and testimony of lawmakers, the Immigration Department has not committed to any changes. While human rights violations at CIC garnered public attention this summer when detainees went on a collective hunger strike, protests and advocacy against the centre have mostly been eclipsed by the intensified and ongoing crackdown under the National Security Law.

While immigration detainees are commonly seen as outsiders who do not warrant our attention and care, advocacy for their human rights is intimately connected to Hong Kong’s overarching anti-authoritarian struggle. Since the arrest and prosecution of protesters intensified over the past few months, we have seen the collusion of power unfold in court, as protesters face charges and sentences that are disproportionately harsh.

Allegations of abuse in Pik Uk Correctional Institution and the inhumane treatment of Joshua Wong in prison further illustrate how the government uses the prison system to retaliate against dissidents.

We, in other words, understand how the criminal justice system in Hong Kong can be used to punish those who do not abide by the government’s agenda. While we rarely connect the pro-democracy movement to the rights of immigration detainees, the injustices perpetrated by the Immigration Department at CIC mirror patterns of oppression and abuse of power elsewhere. Further, as more Hongkongers now seek asylum or refugee status abroad, we ought to extend our empathy and act in solidarity with those detained under Hong Kong’s oppressive immigration policies against asylum-seekers and migrants.

Currently, the CIC holds about 300 immigration detainees, including some who are in Hong Kong to seek asylum as they flee persecution in their home countries. As students from CUHK’s social work department point out, while asylum-seekers await a decision from the Immigration Department, they are held indefinitely at the facility without clear explanation. When pressed about its detention policy, the Immigration Department often argues that detention is necessary as there are criminal offenders among the detainees. This argument can be persuasive because it echoes common racialised portrayals of migrants as outsiders and criminals.

It, however, does not represent the whole picture as detainees have reported unexplained arrest and detention at CIC without any criminal charge. There have also been cases in which migrants were detained at CIC for years even after serving their time in prison. It is important to recall that the argument used by the Immigration Department to justify detention has also been mobilised by the police and government against pro-democracy protesters: law enforcers and the government have repeatedly portrayed activists and dissidents as threats to Hong Kong’s public safety who must be prosecuted and locked up.

We need to extend our interrogation of police and government discourse to the Immigration Department as well, because the abuse of power which immigration detainees experience is akin to, if not worse than, that suffered by Hong Kong activists.

Pro-democracy protesters and the immigration detainees at CIC are both seeking more openness. Throughout last year’s protests and well into 2020, activists have been calling for increased transparency and accountability for the police and the Correctional Services Department over violence against protesters. The Immigration Department is similarly opaque and possesses a great deal of power without proper checks and balances. These systems of power are, in fact, intimately connected.

Migrants rights activists Father Franco Mella and Eddie Chu noted that the CIC was previously managed by the Correctional Services Department. Patterns of abuse and inhumane practices that are prevalent in prisons and detention facilities are, therefore, commonly implemented in CIC. Because of the lack of public attention to immigration detainees, Chu likened CIC to “a black box within a black box.” Echoing the complaints by Hong Kong activists about the lack of police accountability, there are no independent mechanisms to review whether the Immigration Department is abusing its power. The Immigration Ordinance allows the Director of Immigration to detain people at the CIC for an unspecified period, and detainees have little recourse or resources to contest their detention.

Earlier this month, the Hong Kong government proposed a legal amendment to the Immigration Ordinance. This proposal, if passed, would limit people’s freedom of movement in and out of Hong Kong, and would also arm immigration officers, including staff members at CIC, with guns and live ammunition. In an interview, former pan-democratic lawmaker Lam Cheuk-ting argued that this law could potentially give the Director of Immigration the power to lock in Hongkongers who attempt to flee, “like the Uighurs in Xinjiang.”

The civil liberties of mainstream Hongkongers, in other words, are inextricably linked to the rights of asylum-seekers and detained migrants. Without opposition voices in the Legislative Council to contest this proposal, it is all the more important for us to support the work of the CIC Detainees’ Rights Concern Group and the Justice Centre which has been offering legal assistance to asylum-seekers and immigration detainees.

By advocating for those most vulnerable to abuse in Hong Kong’s interconnected system of incarceration, we are protecting the interests and safety of all of us in the city.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.