Today it is commonplace for pundits, scholars and officials to refer to a “Cold War” between China and the United States. Indeed, Chinese officials and media routinely lament “Cold War thinking” in Washington, and the way in which many US politicians speak of China does seem to confirm that such thinking exists.

Is all of this just talk, or is a Sino-US Cold War actually underway? If so, when did it begin, and why? To answer these questions, it’s helpful to look back at the 20th-century Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

That was defined by the political, economic, ideological and military rivalry between the Americans and the Soviets. What many are describing as a Sino-US Cold War shares many of the same attributes: political rivalry has reached near-fever pitch, economic rivalry is growing rapidly, ideological rivalry is near-total and military rivalry is approaching levels that could precipitate direct conflict, perhaps due to naval miscalculations in the South China Sea or US support for Taiwan. By the definition of the US-Soviet Cold War, a Sino-US Cold War does indeed seem to be underway.

When did this new Cold War begin? Before answering that question, it’s worth bearing in mind that the origins of the US-Soviet Cold War are subject to much debate among historians. Some date it to 1917 and the takeover of the Russian Empire by communist forces and the advent of the Soviet Union. Others pick World War II when – despite the US-Soviet alliance in the fight against Germany – Stalin’s plans to dominate postwar Eastern Europe were becoming clear. Some scholars cite 1947 and President Harry Truman’s pledge, in what became known as the Truman Doctrine, to oppose communist expansion in Europe and beyond.

When did the Sino-US Cold War begin? Much as with its predecessor, there’s a case to be made for different dates. Some might argue it started in 1949 with the founding of the People’s Republic of China by the Chinese Communist Party. From this perspective, the communist takeover created an inevitable clash of ideologies that, once coupled with Chinese economic and military power, would – much as in the US-Soviet Cold War – inevitably result in great-power confrontation.

Others choose 2012 and the ascendancy of Xi Jinping to the top of the Chinese Communist Party and his inauguration as president. From this perspective, the growing animosity can be attributed to Xi’s personality, particularly his desire for total control over a self-declared Greater China and its hinterland – including Hong Kong, Taiwan and the South China Sea – and his intention to establish China as a “peer competitor” of the United States and as the unrivalled hegemon in East Asia and the Western Pacific.

Extending this argument, the Sino-US Cold War was inevitable even without Donald Trump. Had he never become president, it might have looked slightly different today but would still have evolved.

These and similar explanations for the beginning of the Sino-US Cold War have their adherents, but setting a more precise date requires us to consider events in Hong Kong. After all, it is these events over the last 18 months that have garnered so much attention in the United States, heightening American fears of what they see as China’s nefarious and unstoppable rise.

Despite what may be the most intensely partisan atmosphere in US history since the Civil War, in which politicians differ on virtually everything, on one topic alone they are in total agreement: Beijing’s actions in Hong Kong are dastardly and unacceptable.

This explains the overwhelming support last year for the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act and more recent legislation calling Chinese and Hong Kong officials to account for their actions against advocates of democracy and freedom.

Trump once declared that events in Hong Kong were a matter for China alone. Congress disagrees. Republican members of Congress, the majority of whom have seen no wrong in anything that Trump has said or done despite his repeated outrages, joined with their Democratic rivals to force his hand on the topic of Hong Kong.

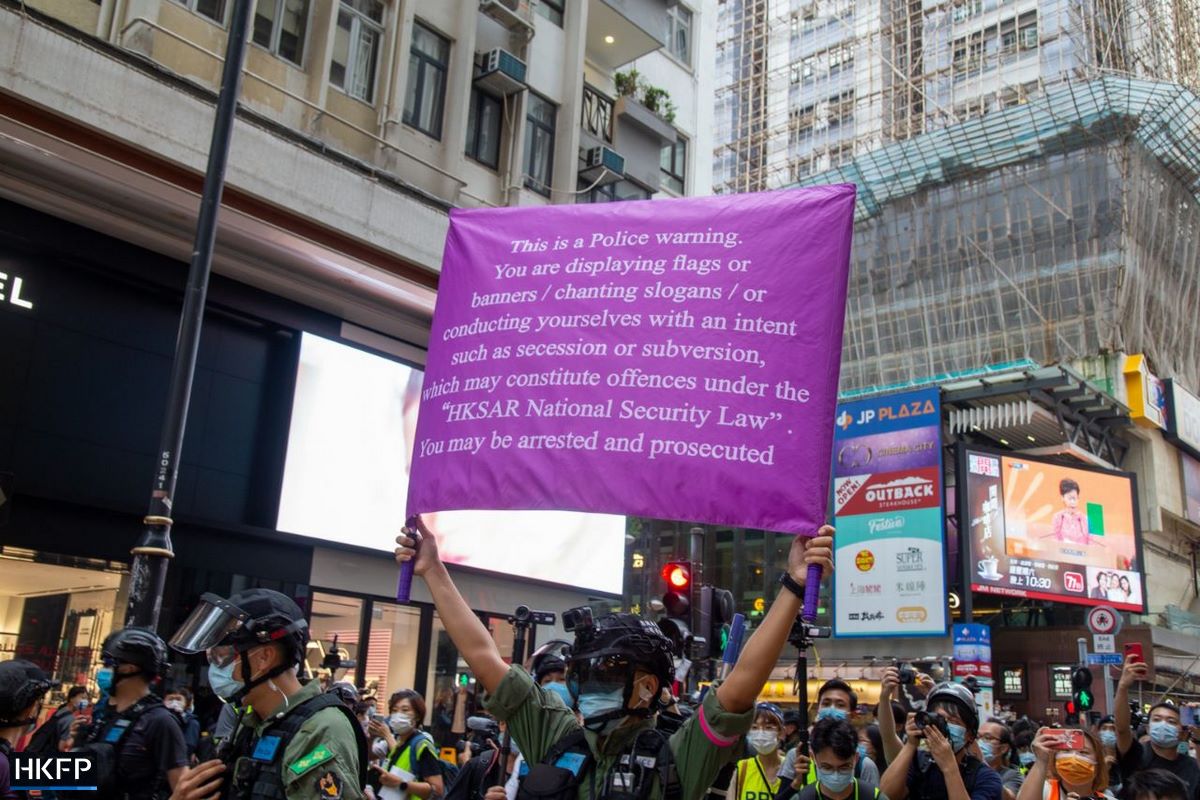

Put another way, the crackdown underway in Hong Kong – the prosecution and imprisonment of rivals of the local government and a National Security Law intended to strangle protests and silence opponents of Communist Party rule – has galvanised concern in the United States about the growing threat to the free world posed by China. In much the same way, events in Berlin during the early years of the US-Soviet Cold War galvanised concern about the Soviet threat.

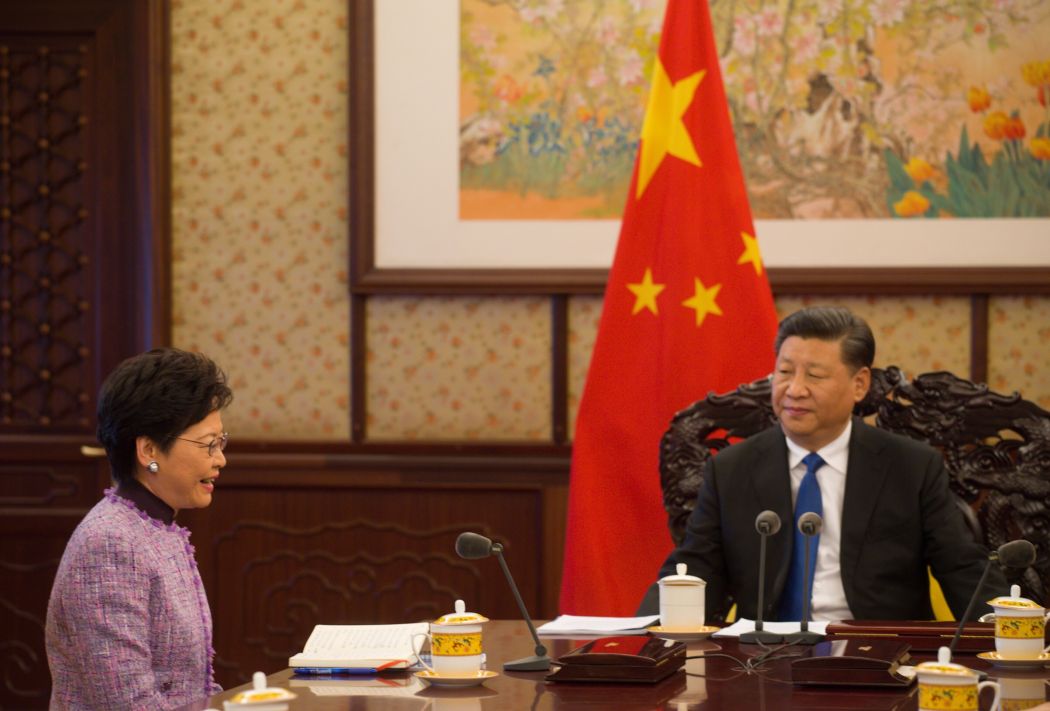

But we can be even more precise in locating the spark that ignited the Sino-US Cold War: it may have been the day in 2019 when Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam made the decision to introduce an extradition bill. This was ostensibly to allow the transfer of a murder suspect from Hong Kong to Taiwan, but would also have allowed the extradition of Hong Kong people wanted in mainland China.

The bill was a step too far for millions of Hong Kong people and triggered months of mass marches and protests. These started with a simple demand: that the bill be withdrawn. When the police responded to peaceful protests with increasingly routine violence, they themselves became a subject of protests. The extradition bill was belatedly withdrawn but protesters considered that to be too little, too late. Violence ensued. Ultimately, the unrest was used by Beijing to justify the National Security Law.

What is perhaps most striking about these events is that, by all accounts, Carrie Lam did not consult widely, if at all, before deciding to move forward with the extradition bill. Whether the idea was planted in her head by others or formed autonomously, it is incredible that one person’s thinking seems to have been the proximate cause of such radical change in Hong Kong. In turn, that thinking – what some would characterise as arrogance – was the catalyst for American action, the subsequent Chinese reaction and the blossoming of a new Cold War.

Historians may one day look back and identify the date in Carrie Lam’s diary when she expressed her desire for greater extradition powers as the day when the Sino-US Cold War began.

It’s impossible to know when it will end but one thing is certain: there’s nothing that Beijing fears more than a conclusion similar to that of the US-Soviet Cold War, the fracturing of the Soviet Union into its ethnic and national components. Regional identity, whether in Latvia, Ukraine or Russia itself, never died out under the communists and re-emerged the moment that Soviet power in Moscow weakened.

This explains the crackdown on freedom underway in Hong Kong, much as it explains what has happened in Tibet and Xinjiang: it is an effort to snuff out local identity and pride and instill identification with, and above all loyalty to, the Chinese party-state. Beijing will never acknowledge weakness on its own part nor brook the slightest opposition in any place under its rule.

The great irony is that the crackdown on Hong Kong is itself fuelling the Sino-US Cold War and, very likely, a decades-long global alliance of democratic states intent on containing China’s power, much as they did the Soviet Union’s. To a significant degree, the emergence of that alliance is due to what went on inside Carrie Lam’s head in 2019.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.