By Sebastian Skov Andersen and Philip Naudus

For months leading up to its release, protesters in Hong Kong urged the world to #BoycottMulan, Disney’s new live action movie adaptation of the millennium-old Chinese folk tale.

The calls quickly spread to other Asian destinations such as Thailand and Taiwan, where activists are fighting to introduce or preserve freedom and democracy. Disney’s decision to cast Liu Yifei as Mulan was unwelcome in Hong Kong because she had expressed support for the Hong Kong police during the pro-democracy protests of last year.

Overseas sympathisers of the movement, mostly in Europe and America, have likewise vowed to boycott the newly-released movie, partly because some scenes were filmed in northwest China’s Xinjiang region, where Beijing is accused of incarcerating millions of mainly Muslim Uighurs.

Last August, Liu shared a post on Weibo, a Twitter-like social media platform in China, which stated: “I support the Hong Kong police. You can all attack me now. What a shame for Hong Kong.”

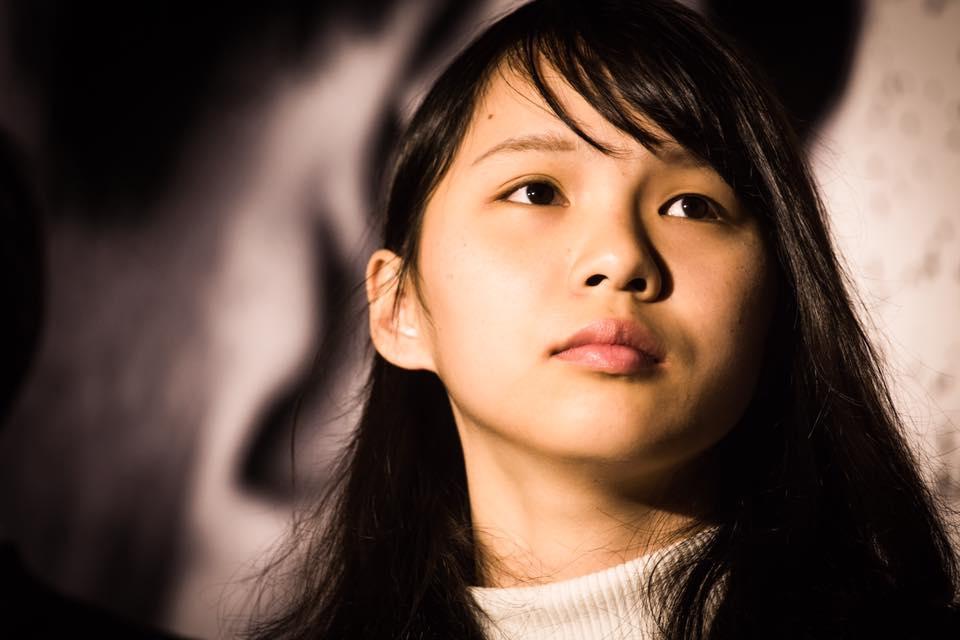

Protesters have argued that casting an actress who supports an authoritarian government in the role of an iconic liberator and freedom fighter does not make sense. Some even launched an internet campaign after pro-democracy activist and former Demosisto spokeswoman Agnes Chow was arrested last month, hailing her as “#therealmulan” and photoshopping her face onto Disney advertisements for the new movie in place of Liu’s.

The message: if anyone is a freedom fighter, it is Chow, not Liu.

#AgnesChow brave protect freedom, democracy, human rights.

— karen like milk tea (@YeungTea) August 12, 2020

She’s definitely Hong Kongers’s #theRealMulan.#周庭さんの無理逮捕に抗議します pic.twitter.com/oxaMXCM48c

But the legend of Mulan has never really told the tale of a freedom fighter, just as it was not tied to social justice until the 20th century. Neither was she much of a feminist icon until Disney adopted her as one — except in the 1920s, when communist revolutionaries used the folklore to urge women to join their army. In fact, the legend has mostly been about sacrificing one’s personal freedoms for a greater cause: to serve one’s ruler or to serve one’s father.

“I don’t think she’s ever been a freedom fighter,” said Louise Edwards, professor of modern Chinese history at the University of New South Wales. “But Hongkongers were searching for freedom fighters so they found Mulan.”

“In terms of the tale’s history, it’s an exception. For the most part, she has been a tool for the patriarchy for whatever it wanted for centuries and centuries,” she told HKFP. “And the Disney movie — I think it gives you a good, fun take on the tale. But the thing is, there are not that many other retellings that portray this rebelliousness.”

Prior to the collapse of imperial China, no adaptations depicted Mulan as a crusader for freedom or for any similarly noble cause. Quite to the contrary, she has often been depicted as an unwavering servant of tradition and culture: someone who would do anything — and serve anyone — to save her father and make sure her family retained its honour.

Either that, or she has been used as propaganda by supporters of the emperor who wanted the Chinese people to give up everything to serve their rulers.

Rather, the rebelliousness was added as an element probably because it appealed to Disney’s target audience: teenagers.

“Disney captured that teenage spirit really well, which nobody would’ve liked and which wouldn’t have made any sense in earlier history. These Disney characters are great fun, but they’re not reflective of anything except a Westernised fixation on teenagers,” said Edwards.

In that sense, the Disney adaptation serves as a strong symbol of how all these Mulan retellings should be understood: as reflective of the society in which they were written and read, often as political commentary or satire.

The origins of Mulan

The earliest known written mention of Mulan is the Ballad of Mulan. This short 6th-century poem, rather apolitical and open to interpretation, tells the tale of a young Mulan who weeps because her father has been drafted. She joins the army herself but the poem skips past all her years of service, fast-forwarding to peacetime when the emperor offers her a prominent position in the military, which she declines. Her only request is that she be granted a camel to take her home.

Because the Ballad is so short, it leaves much to the imagination. According to Edwards, perhaps it is for this very reason that authors throughout the centuries have had an insatiable desire to keep telling her story, and why it has served such diverse purposes.

One of the earliest people to reconstruct what he believed to be Mulan’s true story was Ming Dynasty historian Zhu Guozhen (1557 – 1624). In his book, A Miniscule Book from the Yongzhuang Studio, Zhu hypothesized that Mulan fought loyally in the service of Emperor Yang of Sui. His wars and grandiose architectural projects — most notably the Grand Canal and the reconstruction of the Great Wall — came with a body count that likely surpassed millions, all in the name of honour and prestige.

Many historians have since depicted Yang of Sui as a tyrant. Among them is the late Derk Bodde, a historian and sinologist, who described him as “a ruthless and luxury-loving tyrant who built the Grand Canal and other great public works solely for his own pleasure.”

Though Bodde acknowledged that these structures were beneficial to China economically, progress came at a price. Comparing the emperor to Josef Stalin, Bodde argued that Emperor Yang of Sui’s achievements were “produced only through what was virtually slave labour, and at a tremendous cost of human suffering.”

Although modern historians have since discredited Zhu’s conclusions and concluded that Mulan is a fictitious character, it is noteworthy that an early Chinese historian would consider it logical that a tyrant could command Mulan’s dedicated service.

This was by no means the only occasion on which Mulan was portrayed as sympathetic to an oppressor on account of cultural obligations. During the Qing dynasty (circa 1850), author Zhang Shaoxian wrote the novel The Story of a Fierce and Filial Girl from Northern Wei. In Zhang’s version, Mulan is depicted as devoting her life to the unwavering service of a corrupt emperor, Tuoba Gui.

From history, we know that Tuoba Gui was far from a benevolent leader. He was fond of brutal punishments and notorious for viciously murdering his subjects. The emperor likely introduced to China the practice of forced suicide against the mother of the crown prince, a system which was carried on by his heirs for generations.

This system eventually became known as “if the Son is Noble, the Mother dies” (子貴母死), and ensured that the matriarchal and patriarchal families would never compete for power.

In Zhang Shaoxian’s adaptation of the Mulan legend, Tuoba Gui repeatedly conscripts male soldiers until the supply runs dry. In the opening chapter, the emperor expresses concern that “the heart of the people cannot be commanded,” grants a sword to the army supreme commander, and tasks him with finding conscripts on pain of death for those who do not comply.

Conscripting old and feeble men — such as Mulan’s father — to fill the ranks for the emperor’s bloody expeditions was considered unacceptable, even at that time.

But according to Zhang’s version Tuoba Gui then deployed this army, for which Mulan willingly fought, to quell an uprising not unlike the contemporary Hong Kong protests.

“Zhang’s novel portrays Mulan’s enemies as well-organised rebels motivated by a clear political agenda: to overthrow the ruling emperor. Any action against the emperor was the most heinous of crimes,” wrote Feng Lan, professor of Modern Chinese and American Literature at Florida State University, in an academic article.

“Putting Mulan on the side of the divine order and pitting her against the forces of chaos and destruction makes her accomplishments not only more commendable in a moral sense, but also more ‘politically correct’ from Zhang’s point of view,” he wrote.

In the face of this, Mulan never wavered in her devotion to the emperor. We never get the impression that she despises him for sending her off to suppress an uprising, or considers that the rebels may be justified. Most importantly, she does not even harbour bitterness against the ruler for drafting her aged father.

Mulan the anti-imperialist

Novelists using the legend of Mulan to support their own political ideologies are nothing new. While Zhang wanted to encourage submission to all rulers, regardless of how corrupt they may be, the legend has just as often been used to spark hatred for such tyrants.

The first retelling to take an anti-tyrannical stance was the novel Romance of Sui and Tang, written by Chu Renhuo during the Qing dynasty in 1695. The novel was set in 6th century China during Tujue rule, but it is speculated that it served as political commentary against the dynasty’s Manchu leaders. Contemporary readers would have immediately drawn parallels to their own oppressive rulers.

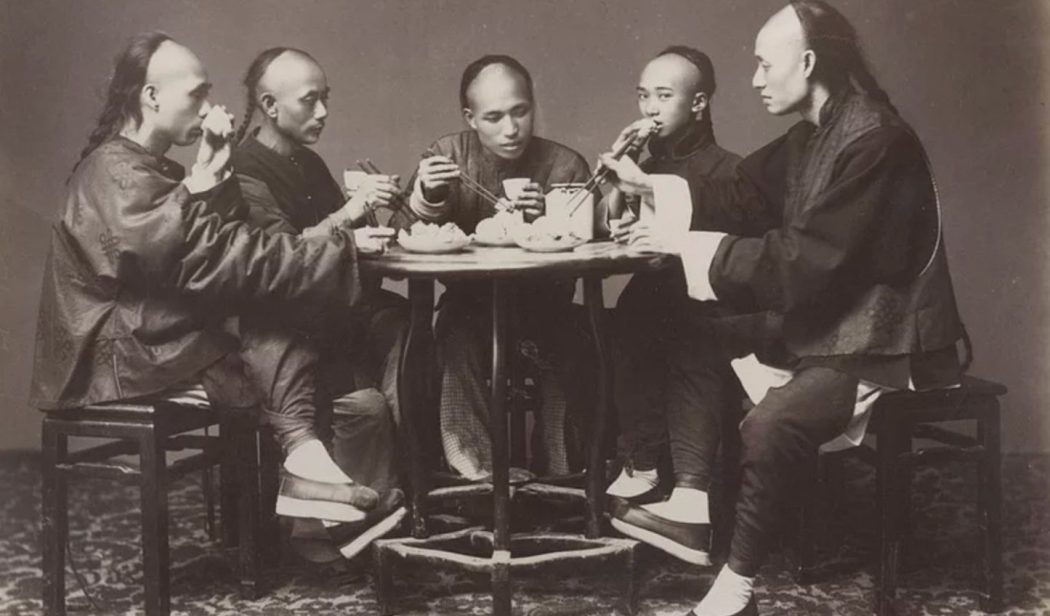

During this period, the Manchu sought to assimilate the Han Chinese into their own culture. One of their methods was to compel men to wear a hairstyle known as the queue.

While hairstyles may seem insignificant, Confucius taught that cutting off one’s hair was equivalent to discarding one’s flesh and a disgrace to one’s ancestors. Many Chinese refused to comply.

During the reign of the Manchu emperor Dorgon, General Li Chengdong and his men were ordered to demonstrate their loyalty to the Qing state by slaughtering their Han neighbours should they insist upon adhering to Confucian teachings, such as by not partly shaving their heads.

As a result, the Han felt justified in their hatred toward the Qing state, which translated into widespread racism against the Manchu as an ethnic group. In this retelling, Mulan is a biracial girl with a Tujue mother and a Han father.

When the story begins she is loyal to the leader of the Tujue. But when Mulan is captured by an enemy princess loyal to a Han Chinese sect known as the Xia, a deep bond is forged between the two women and they become sworn sisters. During this joyous sisterhood, in which Mulan grows fond of her benevolent Han captors, she returns home to bring her parents to live with her in hopes of a happy reunion.

Instead she finds that her father, who was Han, has died and her mother, who is Tujue, has committed a dishonourable act by remarrying. Even worse, the khan has discovered Mulan’s true identity and seeks to take her as his concubine. To preserve her chastity, Mulan commits suicide on her father’s grave.

By rewriting Mulan’s story this way, Chu portrayed the non-Chinese people as barbaric and immoral. He has been known to include openly anti-Manchu and anti-imperialist sentiments in his other works.

While Hong Kong protesters, like Chu’s version of Mulan, are resisting a tyrannical government, they hail Mulan as a hero who defied a despotic emperor, rather than a naive girl who forged bonds with those she originally vowed to overthrow.

A universal hero

The flexibility of the Mulan legend could save pro-democracy Hongkongers from straying too far from the “true” story. In fact, the story changes depending on the purpose for which it is retold: Mulan can be whoever the people need her to be.

“She survived because people stuff her with whatever values suit their usual game or political gain, and she’s a vessel who’s really appealing. So pour in nationalism, and it’s still interesting. Pour in patriarchy, and it’s still interesting,” said Edwards.

It follows then that if you pour in the revolutionary spirit of Hongkongers or the feminist spirit of modern women, the story remains interesting while also staying true to itself. And while the story itself is not necessarily noble — historically or contemporarily — it can still serve a noble purpose.

“Who knows what’s coming from Mulan in the next century? She’ll continue to be used as a sexual object to sell nationalism, the patriarchy or filial piety,” Edwards added. “She could be useful in Taiwan. She could be useful in Hong Kong. In the mainland, and for the Chinese communities in diaspora, and all around the world, you find this enthusiasm from listening to the story about self-sacrifice and dedication to the fatherland.”

In this light, boycotting Disney’s version of Mulan for political purposes is not entirely pointless. Whether or not the criticism surrounding the film is historically accurate, spending one’s money on purposes you support can go a long way, Edwards said.

“If you want to express your political views, then sure, do it through a boycott. Where do you put your $20 for a movie ticket?”

“You’re going to make a choice, so choose.”