In the weeks since Beijing passed the Hong Kong national security law, political titles have been pulled from public library shelves, a protest slogan has been banned and students have been prohibited from political activities in schools. With lawyers, academics, and journalists expressing concern over the law’s vague wording, the future of free speech and expression in the city is uncertain.

Booksellers, like the city’s librarians and publishers, fear stricter regulations on the titles they are allowed to offer, creating a chilling effect among institutions which traditionally uphold and safeguard the free flow of ideas, information, and narratives.

Fears for the independent bookselling arena in Hong Kong first arose in 2015, when five staff members of Causeway Bay Books – which sold political gossip titles – disappeared. Then, in mid-2018, it was revealed that the China Liaison Office in Hong Kong owned the company controlling Sino United Publishing (SUP), which – in turn – controlled more than half the city’s bookstores.

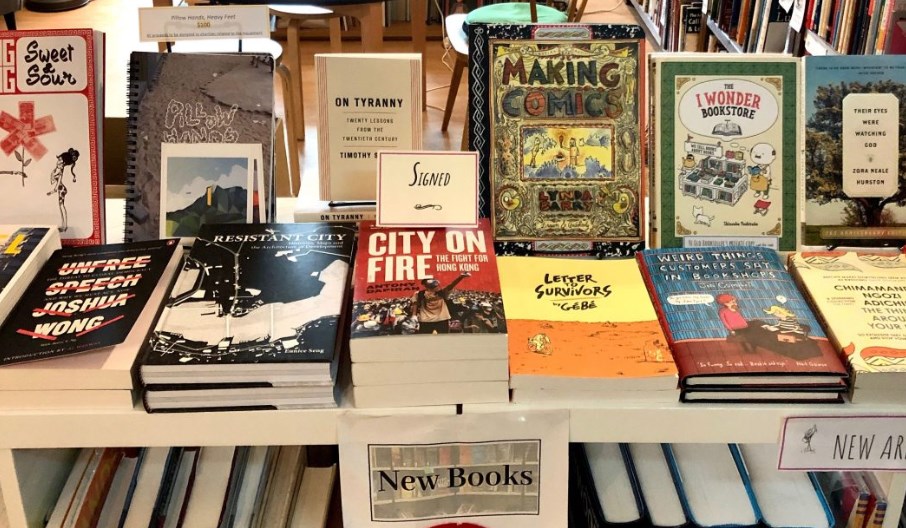

But there are still booksellers in Hong Kong who continue to safeguard against Chinese influence. Albert Wan of Bleak House Books, a local English-language bookstore at the heart of a tight-knit reading community, is committed to resisting any changes in how he runs his business. This includes continuing to stock “sensitive” political titles that could potentially contravene the law: “[These titles] mostly would be books that are not published by large presses. Books that relate specifically to Hong Kong and the law, the Umbrella Movement, or protests from last summer – these are obviously the most sensitive books,” he told HKFP.

He now wonders whether previously unproblematic titles will become contraband: “Under the new law, and based on what we know happens in mainland China, would it be a problem to stock 1984, Animal Farm, or On Tyranny? [What about] general theory-based books [or] academic texts about revolutionary movements that have taken place in China in the past? Who knows?”

As a former US lawyer before running his own bookshop, Wan is sceptical about the legal validity of recent government-issued statements about what may or may not be acceptable: “It’s hard to tell where the red-lines are. Everyone’s saying it, but it’s true. It doesn’t help when the government willy-nilly comes out and makes statements about the law or how people might be violating it. There’s no official interpretation. What the government says, at least in my understanding of how things work… their statements are not the law,” he said.

Wan is not the only independent bookstore owner frustrated by the legislation. May Fung of ACO Book – a local bookstore specialising in arts and culture – also expressed concern: “Every publication on any subject is now subject to this national security law. I think it is dangerous and I am somewhat worried,” she told HKFP.

“If we still lived in a society with rule of law and a legal system we can trust, we can go to court and the court will fairly decide whether or not a certain title contravenes the law. But this new national security agency is outside of the government, so that’s not necessarily the case now; we don’t know whether or not they will be fair.”

However, Fung, like Wan, is committed to “business as usual,” unless forced to do otherwise. “I won’t stop operations because [the government] may or may not ban certain titles. We will keep doing what we are doing until we are forced into a corner,” she said.

Resisting self-censorship

Since the anti-extradition law protests started last June, Wan and his store have taken a clear stance in support of the pro-democracy movement. He says that, especially for indie bookstores like Bleak House, it is difficult to stay apolitical.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being apolitical, it’s really up to the person who runs the bookshop. I think it’s a problem to not have a stance personally, but it doesn’t necessarily have to translate into what you do for work,” he said. ” [But] it’s a little hard to do that when you’re selling books… the books you stock reflect the perspectives and the ideologies of the person or people running the bookshop… it’s harder for smaller bookshops to be in the middle and not take a side.”

When asked whether he will obey orders to pull books off his shelves for the sake of national security, Wan gave a tentative answer: “We would not go and start pulling books off our shelves just because we receive [an order to do so]. It depends on the nature of the order and what it’ll look like.”

“We are very hesitant to go down the path of any kind of censorship, whether it’s self-imposed or whether it’s imposed from outside because if we go down that road there’s really no turning back.”

Fung echoed the sentiment: “I don’t want to go to prison but I will not self-censor until I absolutely have no other choice,” she said.

Despite their commitment to resisting self-censorship, both Wan and Fung said they have to weigh the risks to their livelihoods and the safety of those around them.

“My initial reaction will be to tell them to ‘f-off,’ but I also have a bookstore to run… I have responsibilities as a husband and father,” Wan said. “It’s a matter of how much I feel like I can keep doing [what I’m doing] and not be a burden and compromise the safety of my family.”

“If they do come and tell us certain books can no longer be sold like we saw with Causeway Books, then I will have to stop selling the titles to protect my colleagues from being arrested,” Fung said.

Business interests

Elsewhere in the city, international bookstores are adopting a more cautious approach under the new law. The manager of a bookstore selling books by a German publisher, who requested to remain anonymous, told HKFP their brand has had to self-censor for the sake of business.

“Following the passing of the national security law, we do feel that the freedom that once existed has been curtailed.” he said. “For example, we used to be very carefree and bold in our displays in art fairs in the city, we even put on display a book about Tibet in recent years.”

This year, however, the new law has forced them to rein in their displays. “We sell lots of books on very diverse subjects. But there is definitely more self-censorship now. At the end of the day, we are a business entity,” he said.

This doesn’t necessarily mean the international brand will steer clear of every potentially problematic title in Hong Kong: “In our shop, we are still selling books by Ai Wei Wei. It’s just for higher-profile events, we now have to be less bold.”

Under the security law, the company is approaching bookselling in Hong Kong with lessons learnt from its operations on the mainland. “While we have healthy business relations on the mainland, we have been careful about the types of books we sell in the mainland Chinese market. For example, we stay away from selling more sensitive books such as those depicting maps or dealing with religion.” the manager said.

Beyond preemptive self-censorship, international bookshops in the city may encounter direct censorship as the law’s implementation unfolds. If told to remove certain titles from their catalogue, the brand would have to comply: “We are a business in Hong Kong and have no choice but to follow the law.”

This, however, is a marked change from the company’s original intentions when setting up operations in the city more than ten years ago: “It’s not necessarily what we want since we set up our regional office in Hong Kong as it was a free city and one of Asia’s capitals with the freedom of publication,” the manager added.

“We can still run a healthy business even with the tighter controls and with more titles becoming more sensitive. However, we will have to see how the new law unfolds to see if we will further expand in the city.”

HKFP also approached other large book chains in the city, including Swindon Books, Bookazine, and HKMoA’s TheBookshop, but did not receive any response.

‘As free as possible’

In spite of the rapidly changing political landscape, booklovers are still carrying on as before. Commenting on whether he has seen a change in his bookstore’s community, Wan was surprised at the lack of immediate change: “We thought that people were going to change their book-buying habits after they passed the law because we have books and literature at the bookshop that some people might deem problematic,” he said. “But… people are still buying the same books they were buying before the law was passed.”

The manager for the German-based retailer suggested that customers themselves still had the agency to resist censorship and the curtailing of freedoms through their spending: “Our customers are using their purchasing power in the same way, they are buying the same titles they did before. “

Likewise, despite the pressures, Wan said he believes bookstores too must continue to play their quiet yet crucial role in facilitating access to knowledge: “[Our] duty is just to keep the flow of information going. To keep it as open and as wide and as free as possible. There’s nothing special they have to do. It’s not like they have to fight back or say anything that’s especially incendiary or provocative,” he said.

He said he has this hope for other bookstores: “Just [keep] doing business the way they used to before the law was passed. Just maintaining that sense of freedom that is a trademark of Hong Kong society. This is what sets it apart from the mainland. To maintain that atmosphere and that culture is important.”

For Fung, keeping her store open and uncensored is a question of keeping knowledge accessible for all.

“I think bookstores play an important role in providing access to knowledge in the community. Not everybody has access to an official education so it’s vital to keep providing a channel of knowledge to society,” she said. “This is important for me, and I think lots of people also believe in this.”

And the future for Hong Kong bookstores? “The fate of bookstores is sort of tied to [Hong Kong] as a society that’s rooted in law and free expression and transparency. You cannot run a bookstore without those core principles in place,” Wan said.

“The way Hong Kong goes, bookshops will go. Right now it doesn’t look good, but who knows? We just have to stay hopeful and keep doing what we’re doing.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team