Professor Jerome Cohen – widely respected as the world’s top China law expert – was once feted as “a friend of China” who advocated US engagement with the country amid Cold War hostilities back in the 1960s.

These days, the outspoken critic of China’s human rights abuses and Hong Kong’s looming national security law, is not sure if he is still seen as a friend by its leaders.

In the 1960s, he was one of a few China experts in the United States who advised US President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissenger on Sino-US rapprochement. Three months after Nixon’s ice-breaking visit to China in February 1972, Cohen was received by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai on his first trip to the country as part of a delegation to promote scientific and cultural exchanges between the two countries. When China started reconstructing a legal system amid economic reforms, Cohen arrived in 1979 and started teaching commerce officials contract and business law. He also introduced concepts of foreign investment and joint ventures.

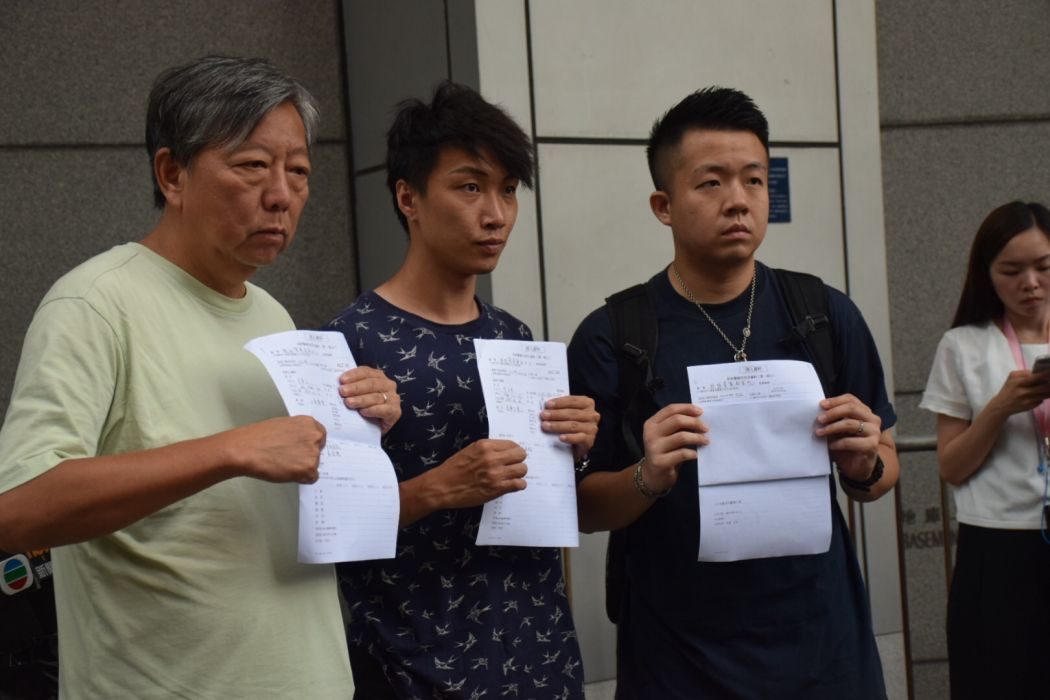

But as China’s economic and political power ascends and it intensifies its suppression of activists and rights defenders, Cohen emerges as one of the staunchest critics of its human rights abuses. He takes a keen interest in the welfare of rights lawyers and activists and often publicly crusades on their behalf.

Turning 90 this Wednesday, Cohen remains active and writes tirelessly on issues that concern him. Of late, he has closely followed the developments in Hong Kong, posting his opinions on the national security law on his blog on an almost daily basis. Cohen, who spent 1963 to 1964 in Hong Kong interviewing refugees for his research on China’s criminal justice system, is particularly concerned about the impact of the sweeping law–expected to be passed in Beijing on Tuesday–on a city he loves.

“Nothing is the end of Hong Kong,” said the New York University law professor. “[But] this is the end of a Hong Kong of free speech and the end of a Hong Kong of due process of law.”

“It’s a dramatic change to the Hong Kong that we have known,” he said. “It will be more and more like the mainland.”

Asked what aspect of the law he was most concerned about, he said: “Just about everything.”

He highlighted the human rights impact of the new law, which according to pro-Beijing media will allow suspects of national security cases to be detained indefinitely in special holding centres. Cohen said these new centres could be administered like the mainland’s “residential surveillance at a designated location”–a form of incommunicado, solitary detention that can last up to six months in a secret location without lawyer or family access, before any criminal process even begins.

“Arbitrary detention is the greatest enemy we confront today,” he said.

He also questions why the system is necessary and is concerned about how national security crimes will be defined and by what criteria the chief executive will select judges.

Based on the explanatory summary of the draft law released by the state and pro-Beijing media, Cohen believes that – after a period of detention in Hong Kong – defendants will be tried by judges handpicked by the chief executive in a special security tribunal, while the more serious cases would be sent for prosecution in mainland courts, where they would be treated like mainland rights activists and lawyers accused of subversion. Mainland courts have a conviction rate of over 99 per cent.

“The institutional framework for implementation is obviously designed to integrate Hong Kong into the mainland security system that subjects the formal criminal justice system to the security agencies,” he said.

The draft stipulates that the Hong Kong government should set up a national security commission chaired by the chief executive, with an adviser appointed by Beijing. The mainland authorities would also establish a national security agency to collect and analyse intelligence and “monitor and supervise” the local government’s work. The Department of Justice, meanwhile, would set up a specialised section on prosecutions related to national security cases whilst police would set up a special unit to enforce the security law. Beijing’s Ministry of Public Security has said it would “fully guide” and support Hong Kong police in safeguarding national security.

“In investigations, there will be much more open surveillance, interrogation by national security authorities and by the new section of police operated under national security law,” he said. “A lot will be done under the central authorities by Hong Kong police who will learn what security agencies will do in Hong Kong.”

He is also concerned how far reaching the law would be and whether people who have advocated independence abroad will be prosecuted if they even pass through Hong Kong.

Officials have claimed that while enacting the law, the authorities will uphold human rights, the presumption of innocence, and other freedoms in accordance with International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Basic Law. But Cohen calls this “eye candy.”

“What they say is nonsense,” he said. “The ICCPR says anyone subject to criminal trial is entitled to [be tried in] fair, independent, impartial courts. What they’re planning is a plain violation of the protections of the ICCPR.”

After his 60 years of engagement with China, Cohen says it saddens him to see the country going down the road of dictatorship.

“This is power politics of a regime determined to demonstrate unquestioned power throughout its territory,” he said. “They want [Hongkongers] to respond like the rest of the people [in China] respond, like trying to make Muslims and Tibet people into Han people…. It’s not going to succeed in the long run. They’re willing to take every repressive measure now to make sure Hong Kong people start marching according to Beijing’s drummer.”

“Of course I feel terribly sad, I feel terribly angry. I feel I have to do everything I can to increase public understanding of what’s about to take place. I have an obligation because of my knowledge and experience of 60 years,” he said.

When he started learning Chinese in 1960, China had just experienced the trauma of the 1957 anti-rightist movement – in which millions of intellectuals were sent to the countryside for hard labour – and was going through the Great Leap Forward, which resulted in the starvation of more than 30 million between 1958-1961.

Cohen called himself a “product of World War Two” who wanted to do what he could for international peace.

HKFP Dim Sum: Subscribe to our free newsletter for a concise round-up of Hong Kong news and our best coverage. Unsubscribe at any time – we will not pass on your data to third parties.

“During my high school years, we had World War Two. We students wanted to save the world another great war,” said Cohen, who finished high school in 1947.

“By 1960, I had hoped to help play a role in preventing a serious war with China. I wondered if the United States could cooperate with China in a way that it had failed to do before, and this seemed to me a worthy cause,” he said.

“It also attracted me because of the challenge of trying to reduce the dictatorship of China which caused violations of human rights that Chairman Mao had inflicted on the Chinese people through the absence of the rule of law,” he said, adding that he wanted to learn from China not only the negative experience, but also to satisfy his interest in the pre-Communist era, including the dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek and the imperial legal tradition. “China looked like a good area to study.”

But his and other American liberals’ ambitions appeared to have failed. In recent years, China’s increasingly strident “wolf warrior” diplomacy and repression at home has caused some to blame the US policy of engagement which has allowed China to grow into a super economic and political power that is rewriting the rule book for international politics.

“I think it’s clear that Chinese people are much better off today than they were in 1979, even though it’s also clear that the last eight years of Xi Jinping’s rule has created China’s most efficient dictatorship,” he said. “Xi insists on absolute silence among the people, repression and absolute uniformity of opinions.”

Cohen said foreign legal experts like himself who helped China to establish a legal system in the decade from 1979 until the June 4 Tiananmen crackdown in 1989 “were not naive about Chinese communism, but we did believe that in helping them build a legal system to attract foreign investment and knowledge of cooperation, that would reduce some of the worst excesses of the Cultural Revolution.”

“We didn’t think we were going to bring democracy to China. We thought we would help provide a legal system that would be more decent in due process of law, that would protect the basics, and introduce more stability than China had before and help it take part in the world in a positive way,” he said.

But they also knew everything was at the mercy of politics. “We couldn’t predict the future of how far this could go… We had no choice but to try to improve the legal system, whatever the political future brought.”

Had China had a more liberal leadership, things could have turned out very differently, he argued.

“Xi Jinping is not the inevitable destiny of Chinese communism. It could have produced more liberal, enlightened leadership” such as reformists like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang – who were purged by conservatives – or Premier Zhu Rongji, a leading economic reformer who was in power until 2003, he said.

“If leaders like that had been able to keep in power, things might have gone a different way,” he said.

Cohen argues that that one has to take a long term view.

He believes that “even at the height of maximum dictatorship,” progress is still being made in important legal procedures at a technical and structural level and these efforts are “preparing for better days.”

“We can’t give up… China has made too much progress in the last 40 years. There is a much better basis for legal reform now than at the time when Mao died, and when Xi leaves the scene, there will be a return to a better life. There will be a more mellow, more enlightened communism than we’re experiencing today,” he said.

“Surely I have not lost hope, since significant progress has been slowly, haltingly made over the decades in the development of a genuine legal system.”

In 1968, at the height of the Cultural Revolution, he predicted in his book The Criminal Process in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1963 (which he wrote from interviews with Chinese refugees in Hong Kong), that “This would not last. There will be reactions by the Chinese people against Mao’s rule.”

Similarly, he believes that people would one day also react against Xi’s rule.

“Today there are millions of educated Chinese still quietly longing for and working toward a more decent legal system and the protection of universal human rights. There will be a reaction to Xi Jinping’s unfortunate suppression.”

“Given China’s enormous population and landmass and its imperial traditions, the process is more difficult,” he said. “But I have to view things with the detached equanimity of an armchair observer who must take a necessarily longer and broader perspective.”

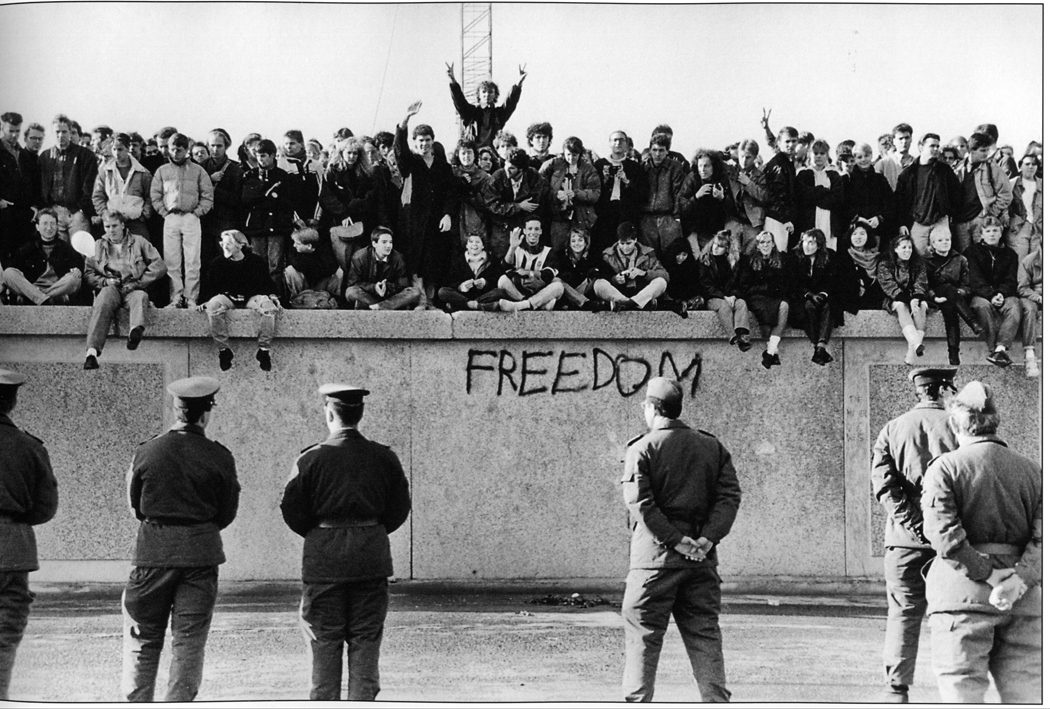

“Perhaps Hongkongers have to think about the fate of people in post-war Prague, Budapest, Warsaw and East Berlin,” he said.