By John Patkin

Much has been written about the scourge of discarded surgical masks that are defacing our environment. They have become ubiquitous and even more notorious than single-use plastic bags and disabled umbrellas.

Laying askew on pavements, hanging from tree branches, and sitting in drains waiting for the inevitable drowning in the next rainstorm, the abandoned face coverings are sobering reminders of the sweeping transformations brought by the coronavirus pandemic.

Lockdowns and physical distancing have led to an immediate reduction in air pollution but also a stark warning about the mountains of waste attributed to single-use personal protective equipment (PPE).

A cursory observation of face mask usage in Hong Kong shows that few people wear reusable ones and they are especially shunning the government’s free one. Hong Kong has made much-needed progress in reducing waste from single-use products, packaging, and home appliances, but the icky factor makes it more difficult to deal with PPE due to our perceptions and ignorance regarding the management of medical waste.

As I work from home, I seldom use a mask. I hate wearing them as they are hot and there is too much fiddling to find the sweet spot on my nose bridge that cuts my exhalation from fogging-up my glasses. I have opted for cloth masks as they are softer and can be cleaned in the washing machine.

Disposable masks are good for what I feel are high-risk activities such as public transport and hospital visits. But I have been toying with an alternative using my 3D printer.

In the early days of Covid-19, a shortage of such products spurred the world’s 3D printing community into action. One of the leading open-source websites for 3D printing, Thingiverse (thingiverse.com), has been running the HackThePandemic challenge to develop face coverings since March. Hobbyists from around the world have been sharing their designs for masks, face shields, social distancing devices, ventilators, and accessories in a friendly worldwide competition of innovation and tinkering.

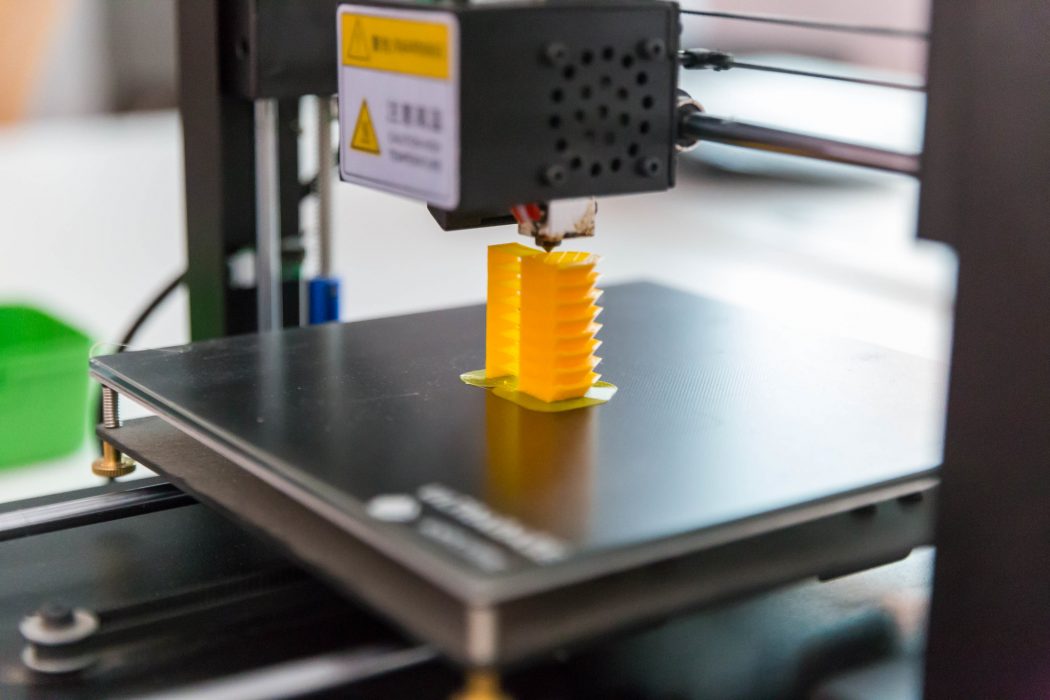

Most 3D printers are sold online and supported with a variety of open-source software. The literal sticking point of 3D printing is consistency.

3D printing is the integration of forcing a hard variety of plastic filament through a heated nozzle that layers it on a fixed flat surface. In desktop printing terms, the filament is like ink and the bed it prints on is paper. In desktop inkjet printers, sheets of paper are cycled through and the nozzle moves along one axis. In 3D printing, the same sheet or printing bed is manipulated laterally on two axes (x and y) as the nozzle (z-axis) ejects liquid filament in layers that form objects. The nozzle increases its distance from the printing surface as it adds each layer. It requires some tinkering to ensure the design, material, temperature, and speed of printing are compatible and that the filament sticks to the printing plate.

The shortage of PPE in the early days of Covid-19 prompted the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) to develop face shields using 3D printers. But there is little evidence that the files and designs have been shared in the same manner as Thingiverse contributions.

While the PolyU’s effort was celebrated in the local media, the final products were average in comparison to the work of hobbyists. What is needed here from the boffins at the PolyU is some leadership to aggregate designs that could be sourced from around the world and adapted to local needs.

During the closure of Hong Kong’s educational institutions, hundreds of 3D printers in school labs were idle and remain so. The upcoming summer break provides an excellent opportunity to use the printers to produce reusable PPE while also encouraging trained engineers, designers, and hobbyists to innovate and tinker.

Due to the relative ease of access to university-based health care researchers in Hong Kong, new designs could be quickly assessed and tested. One of the greatest challenges is to produce a transparent mask that helps lip reading and reveals micro facial expressions. Trialling designs produces waste and some parts will need to be replaced from time to time, but reusable masks are an alternative to single-use PPE.

3D printing has its pitfalls as it can take hours to produce a mask from a home printer and once the scare is over, the masks may be added to landfill. Many of the materials may not pass strict poisons tests based on long term exposure but may be suitable as barriers against Covid19.

Ultimately, a vaccine or eradication would be the best outcome in the war against Covid-19 but in the meantime existing infrastructure and intellectual capital should be utilised to produce PPE for Hongkongers and shared with the global community.