by Jerome Taylor

Millionaire media tycoon Jimmy Lai knows his support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests could soon land him behind bars, but the proudly self-described “troublemaker” says he has no regrets.

“I’m prepared for prison,” the 72-year-old told AFP from the offices of Next Digital, Hong Kong’s largest and most rambunctiously pro-democracy media group.

“If it comes, I will have the opportunity to read books I haven’t read. The only thing I can do is to be positive.”

Few Hong Kongers generate the level of vitriol from Beijing that Lai does.

For many residents of the restless semi-autonomous city, Lai is an unlikely hero — a pugnacious, self-made tabloid owner and the only tycoon willing to criticise Beijing.

But in China’s state media he is a “traitor”, the biggest “black hand” behind last year’s huge rallies and the head of a new “Gang of Four” conspiring with foreign nations to undermine the motherland.

For years a mysterious group of self-described “patriots” has picketed his mansion.

During AFP’s visit, a man parked a van outside Lai’s offices with a digital screen broadcasting various allegations and internet conspiracy theories suggesting Lai is an American stooge.

Lai said he had learned to meet such descriptions with laughter.

“Whatever they say I don’t pay attention because they say whatever they like. The van, though, that’s a new one,” he said, chuckling.

‘It feels right’

Lai’s life story is typical of many of the rags-to-riches journeys made by Hong Kong’s tycoons.

He was born in mainland China’s Guangdong province into a wealthy family who lost it all when the communists took power in 1949.

Smuggled into Hong Kong aged 12, Lai toiled in sweatshops, taught himself English and eventually founded the hugely successful Giordano clothing empire.

But his path diverged from those of his contemporaries in 1989, when China sent tanks to crush pro-democracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

He founded his first publication shortly after and penned columns regularly criticising senior Chinese leaders.

Authorities began closing his mainland Chinese clothing stores, so Lai sold up and ploughed the money into a tabloid empire.

Asked why he didn’t just keep quiet and enjoy his wealth like Hong Kong’s other tycoons, Lai smiles.

“I just fell into it, but it feels right doing it,” he said.

“Maybe I’m a born rebel, maybe I’m someone who needs a lot of meaning to live my life besides money.”

Prosecutions and payback

Lai uses laughter to downplay the risks he faces. But he is in the crosshairs more than ever.

He is currently being prosecuted alongside 14 other prominent pro-democracy activists for taking part in last year’s rallies, on charges that carry up to five years in jail.

He declined to discuss the case, for legal reasons, but said he was unrepentant about attending and supporting protests over the years.

“I’m a troublemaker. I came here with nothing, the freedom of this place has given me everything. Maybe it’s time I paid back for that freedom by fighting for it,” he said.

The newest threat is Beijing’s plan to impose a new national security law on the city, which would outlaw subversion, secession, terrorism and foreign influence.

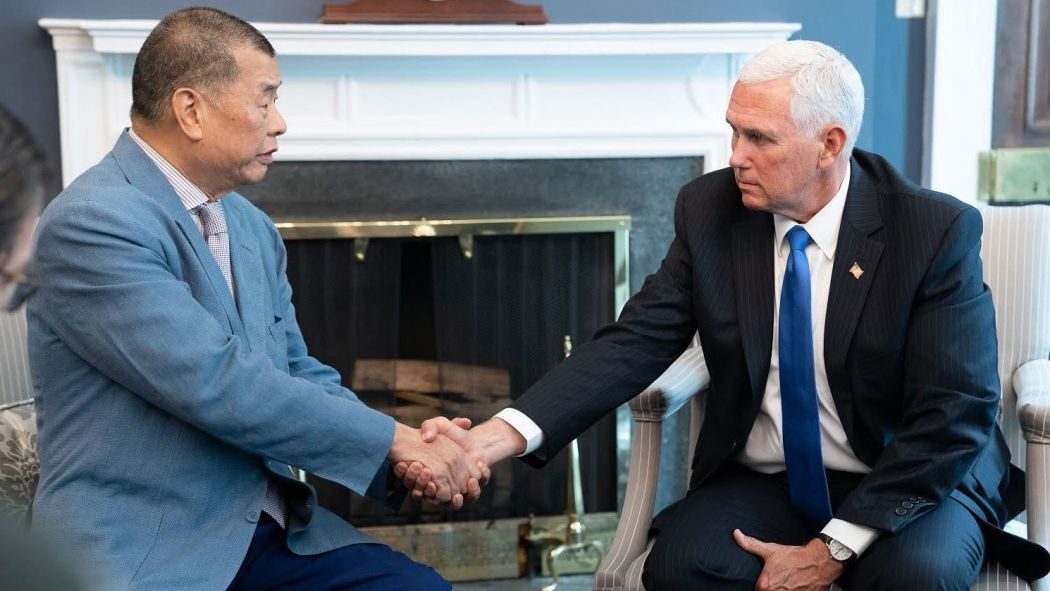

Allegations of Lai colluding with foreigners went into overdrive in state media last year, when he had a meeting with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Vice-President Mike Pence.

Lai described the proposed law as “a death knell for Hong Kong”.

“It will supersede or destroy our rule of law and destroy our international financial status,” he said.

He also fears for his journalists.

“Whatever we write, whatever we say can be subversion, can be sedition,” he said.

‘External enemies’

His two primary titles — the Apple Daily newspaper and the digital-only Next magazine — are unapologetically pro-democracy in a city where competitors either support Beijing or tread a far more cautious line.

Apple Daily’s newsroom is crammed with pro-democracy slogans, cartoons and mascots.

The two publications have been largely devoid of advertisements for years as brands steer clear of incurring Beijing’s wrath, Lai plugging the losses with his own cash.

But they are popular, offering a heady mix of celebrity news, sex scandals and genuine investigations such as a recent series looking at how the houses of some senior police officers violated building codes.

Lai also publishes a Taiwanese version of Apple that is vocally critical of Beijing.

China is at its weakest point in decades under President Xi Jinping, its once-booming economy threatened by the coronavirus, the trade war with Washington and rising international concerns about its ambitions, according to Lai.

“The communists, when they are in crisis internally, they need to create external enemies to unite the people,” he said.

“That’s why all of a sudden he (Xi) has become so aggressive and belligerent to Taiwan and is imposing a national security law in Hong Kong.”

That leaves Hong Kong in a potentially precarious position. But Lai said he had no plans to leave the city, or moderate his views.

“The only thing we can do is persist, not to lose spirit or hope,” he said.

“And to think that what is right will eventually prevail.”