When Mary saw a job advertisement recruiting foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong on Facebook three years ago, her face lit up.

The 29-year-old Kenyan thought the monthly wage of HK$4,410, way higher than her income at home in Nairobi, would contribute towards paying for the education of her six siblings whilst supporting her retired parents.

“I trusted the agent who told me that Hong Kong was a good place with good people,” said Mary, a former beauty shop owner who had also worked in Saudi Arabia as a domestic helper. “I was expecting better living conditions and a higher salary.” But now, she described her working conditions in Hong Kong as “worse than Saudi Arabia.”

Mary never foresaw that her “dream job” would turn into one of her worst nightmares.

Before she left for Hong Kong, the employment agency told her she would be charged a placement fee of HK$24,000, which would be deducted from her salary over the first six months of her employment. The monthly deduction of HK$4,000, or 90 percent of her pay, meant she would only have around HK$400 per month in her pocket for her first half a year in Hong Kong.

Mary, unaware that agencies are supposed to charge domestic workers no more than 10 percent of their first month’s salary under Hong Kong law, thought the placement fee was hefty. But her family desperately needed money and she felt she had little choice but to consent to it.

More shocks were to come when she arrived in the city in May 2018.

Her employer required her to work from 5:30am until 11:30pm every day. During the first three months, she had to work seven days straight, with no rest day. While she was eventually given a weekly “day off” after her three-month probation ended, her employer gave her just four hours off. After she complained, she was given eight to nine hours off, although she had to clean and cook before going out, and had to do household chores upon her return. Hong Kong law mandates that domestic workers be given a rest day for a continuous period of at least 24 hours every seven days.

Her agent, when contacted by HKFP, said the workers were given pay in lieu for rest days during their probation and they had signed to consent to such an arrangement. It is, however, illegal under Hong Kong law for employers to compel an employee to work on a rest day.

“I was always hungry. When I asked for

Mary

food allowance, my employer said no and

I had to use my own money to buy food…

I was scared and cried all the time…”

Mary complained about other irregularities, including not being given statutory holidays and having her bank card and passport confiscated by the agent until the placement fee had been paid.

Mary’s living conditions added to her misery. At the end of an 18-hour day, she often went to bed hungry. She said she was never given breakfast and rarely given lunch. For dinner, she was given only a slice of bread and a small portion of vegetables. Every night, she struggled to sleep on the floor of a stuffy, cramped storage room where cockroaches sometimes crept along the walls.

“I was always hungry. When I asked for food allowance, my employer said no and I had to use my own money to buy food,” Mary said. “I was scared and cried all the time, because things were different from [what was in] the contract.” Her contract stated that a monthly food allowance of HK$1,053 should be paid by the employer if food was not provided.

As one of just 17 Kenyan domestic helpers in Hong Kong, Mary felt desperate but did not know where she could find help.

Left with only a few hundred dollars in her pocket after the hefty deductions for the first six months, Mary was also unable to send home the much needed cash.

“I wanted to send money back but I couldn’t. [My siblings] would ask why I didn’t send money home, and I had to tell them to wait,” she said.

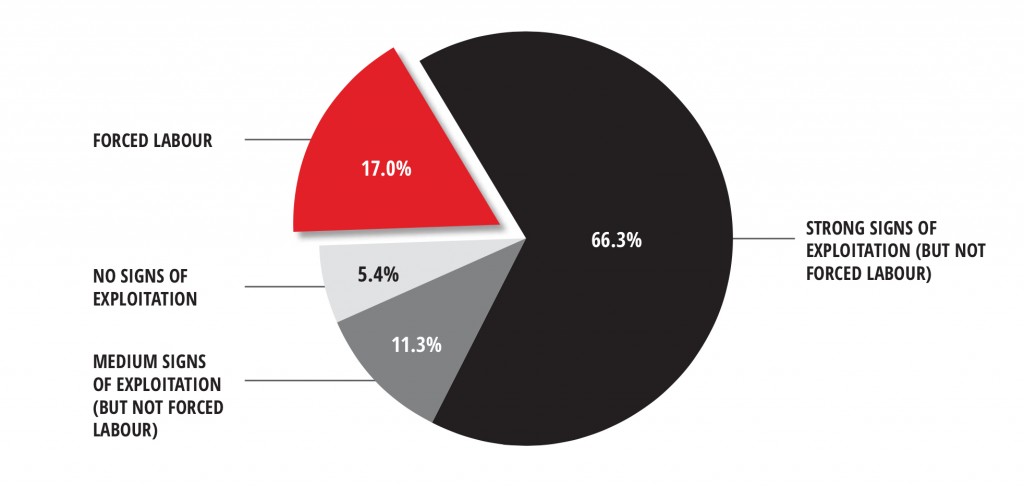

Mary is only one of tens of thousands of foreign domestic workers regularly exploited in Hong Kong. A report by Justice Centre Hong Kong in 2016 showed that one in six workers was a victim of forced labour in the city. When extrapolated to the entire domestic worker population – which was 336,600 at the time – over 50,000 workers were believed to be engaged in forced labour. More updated figures are unavailable.

The 2016 study also highlighted that migrant domestic workers like Mary who had excessive debts – which often amount to more than 30 percent of their annual income – were six times more likely to be in forced labour than those without high debt.

After being assessed by a member NGO of the Civil Society Anti-Trafficking Task Force, Mary was identified as a victim of human trafficking for the purpose of forced labour.

The initial assessment report said Mary was made to pay an excessive sum of money as a recruitment commission which was substantially higher than the commission allowed by Hong Kong law. The debt incurred from the recruitment fee also left foreign helpers with no choice but to be trapped in their jobs.

A UN-linked intergovernmental organisation, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), would not directly state whether Mary was trafficked, but said that the nature of her allegations could amount to such a case. They have nevertheless identified a total of 88 victims of Trafficking in Persons in Hong Kong between August 2017 and January 2020. Among them, six were Kenyans.

“When people think about forced labour, they think of chains and old school slavery. But the International Labour Organisation defines it as situations in which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation, or by more subtle means such as manipulated debts,” said David Bishop, a business law lecturer at the University of Hong Kong and the co-founder of Migrasia, an NGO which helps exploited foreign domestic workers.

HKFP spoke to three other Kenyan domestic workers who also said they either took out a loan to make a one-off payment to their agency before coming to Hong Kong, or had agreed to salary deductions over several months.

Manisha Wijesinghe, director of case management at HELP for Domestic Workers, said the overcharging of agency fees, denial of rest days and underpayment or non-payment of wages are common types of exploitation faced by the entire foreign domestic worker community in Hong Kong.

She said exploitation – which also includes physical assault – has been continuing because the government only acts on individual cases, rather than working on the wider issue.

“The existing system is a very piecemeal, where you have the Labour Department, Immigration Department and Police considering cases on a separate basis,” Wijesinghe said.

She added NGOs tend to be less equipped to help smaller communities like Kenyan, Indian and Sri Lankan domestic workers, limited by the language barrier. The lack of community support may also discourage workers from minority groups from seeking assistance.

You see a lot of cases falling through

Manisha Wijesinghe, HELP FOR DOMESTIC WORKERS

the cracks and not being reported.

“You see a lot of cases falling through the cracks and not being reported. Unless there is a support system from the community, the NGOs and the government, most of these cases don’t come forward,” Wijesinghe said.

Eni Lestari, chairwoman of the International Migrants Alliance, told HKFP that the placement commissions slapped on Kenyan domestic workers by their agencies were double the amount charged to Indonesians. And the small number of Kenyan domestic workers – just 17 according to the Immigration Department figures – means their plight tends to be “invisible”, she said.

The Hong Kong government has been under pressure to improve the protection of foriegn domestic workers after shocking cases of abuse made international headlines. One of the most high-profile cases involved Indonesian worker Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, who was starved and beaten by her employer during eight months of employment in 2013.

The Hong Kong government launched a cross-bureau action plan in March 2018 to combat human trafficking and step up protection of foreign domestic workers in the city. The plan sets out to implement a screening mechanism in the Labour Department and law enforcement agencies to spot potential foreign domestic workers and other vulnerable groups who are exploited, abused or trafficked.

Based on Security Bureau figures, among over 19,000 people screened between 2017 to 2019, only 30 – three of them Kenyans – have been identified as victims of human trafficking.

At a Legislative Council meeting in January last year, Secretary for Security John Lee cited the low number of trafficking victims identified as evidence that human trafficking was not “prevalent” in Hong Kong and dismissed recent human trafficking reports published by the US Department of State in which Hong Kong was listed as Tier 2, the same ranking as Germany, Mexico and Uganda.

But human rights lawyer Patricia Ho disagreed with the government’s conclusion, arguing that the low number was in fact due to the government’s faulty assessment system. She said a questionnaire used by government departments to identify potential trafficking victims contained unclear wording that could affect the screening result.

“Unless a victim is assisted by a lawyer, there is no way that they would be able to prove to the authorities that they are a victim,” she said.

Rachel Li, research and policy officer at Justice Centre Hong Kong, a non-profit human rights group, criticised the government for not taking human trafficking seriously, and said it has little understanding of exploitation and forced labour.

“They are reluctant to admit that there is a problem. This attitude translates into policies that simply disregard the need to offer protection to victims of trafficking,” Li said.

In September last year, after working for 16 months, Mary decided she could no longer put up with her situation and handed in her resignation.

Mary filed her case to the Labour Tribunal in December to seek compensation from her former employer for unpaid food allowance and compensation for working on rest days, statutory holidays and annual leave. But her employer has denied mistreatment of Mary and refused to pay most claims.

She has been staying at a shelter provided by NGO Christian Action on a visitor visa while awaiting the outcome and seeking a new employer.

Mary and three fellow Kenyan domestic workers, who have all been recognised as victims of human trafficking for the purpose of forced labour, hope their cases will serve as a lesson for other migrant workers.

“It is really bad what has happened to the Kenyans here,” said Esther, 38, another of the Kenyan domestic workers who faced exploitation in Hong Kong. It’s disappointing. I’m no longer worried about myself, but I’m worried about those who don’t know what’s happening.”

Additional reporting: Rachel Wong.