As Hong Kong ushers in a new year (and a new strain of deadly coronavirus with accompanying paranoia), it seems appropriate to pause and take stock of the current state of the city’s embattled protesters, who continue to face sustained, uncompromising resistance from the Hong Kong government.

Authorities have so far proven unwilling to recognise the protests as anything other than the rioting of inexplicable pockets of terrorists, and have refused to alter or apologise for the tactics of their street-level representatives – the Hong Kong police force. But demonstrators have also suffered from a disheartening perception that the protests are, in some way, dissipating. To buy into this idea would be to think incorrectly about how the seeds of discontent were sown in the first place, and to ignore the inevitable effects on Hong Kong’s long-term social stability.

Beneath the surface, the protest ‘crisis’ is about opposition: partly to the ideology of the central government and its encroachment on Hong Kong liberties, and now partly to authority in general.

Recalcitrance has become a point of honour for many as embitterment deepens. Even more precisely, the “crisis” is about identity and factionalisation amongst Hong Kong citizens, who have conflicting interpretations of Hong Kong as ‘home’, in terms of support or opposition to the local and mainland governments and their response to the protest movement.

The protests have solidified a divide in the city that ensures neither side can emerge victorious on its own terms, while complicating formulation of a contemporary Hong Kong identity. This battle is being fought on the plane of ideas. The relative lull in physical confrontations between protesters and police since the district council elections in November does not signify the death-throes of the pro-democracy movement.

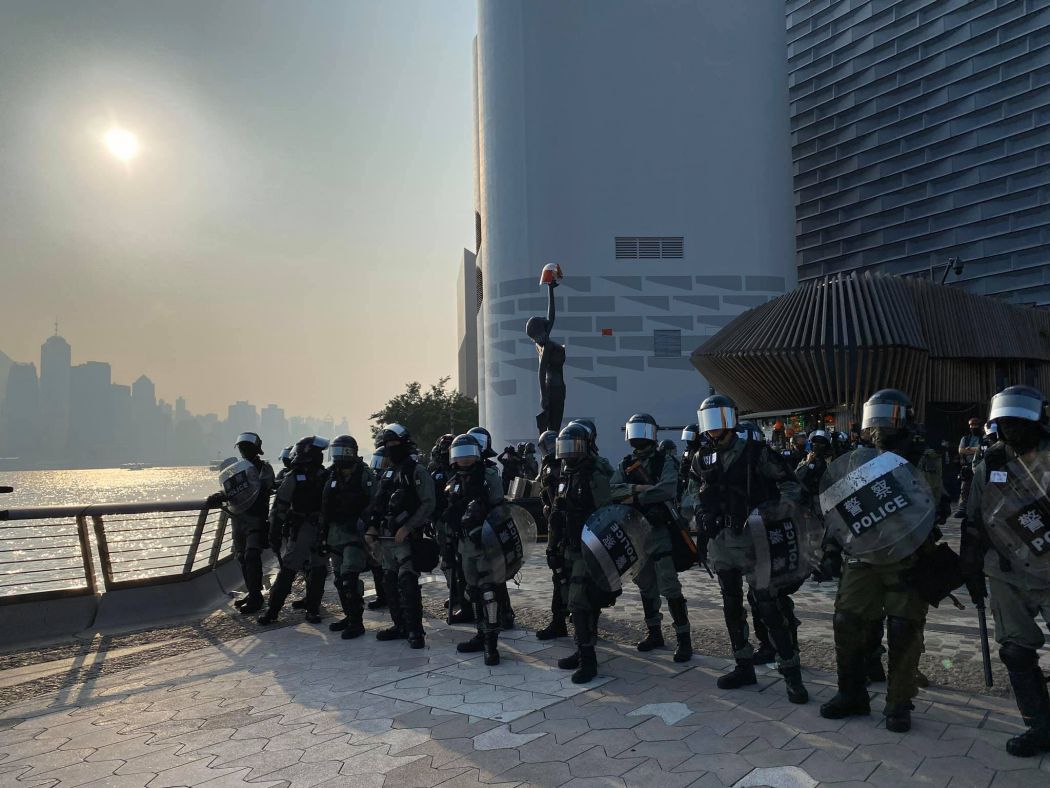

Protesters’ persistence, sometimes gathering on a daily basis, throughout the summer and much of the autumn, has not been conquered. Gatherings still take place; (arguably purposeful) public disruptions and acts of vandalism are still committed; and police still retaliate with predictable swiftness and force. The difference is only that such events are less regular and are attended not just more sporadically, but more exclusively.

We should, therefore, think of the smaller physical presence of protesters as a distillation of the motivations and core values of the movement: political agnostics – never really comfortable standing around Mong Kok station at one in the morning – have left; some of the arsonists and troublemakers are burnt out. And unlike those opportunistic individuals who boisterously hurl obscenities from a safe distance towards police officers and their poor mothers, the present band of regular protesters symbolises a more credibly political objective.

Merely by expressing themselves over such a long period of time – at least in comparison with the 2014 Umbrella protests – these individuals represent the accumulation of the public’s anger and distrust of authority, born long before resentment erupted into action.

The longer these protesters are visible – and this is the merit of them merely showing up – the clearer the message to the government: we Hongkongers are increasingly cultivating our identity both in spite of and in direct opposition to your politics. This is the first potentially-catastrophic challenge posed to the authorities. We might express the protesters’ interpretation of their identity as Hongkongers in the following terms: defiant, dissident individuals – even, if need be, violently so – striving for social and political reform.

The precise terms of this reform, other than the five key demands, remains unclear. But these goals generally centre on improving the state of democracy in Hong Kong.

As this anti-authoritarian identity is consolidated – paradoxically, by the very forces intended to stamp it out – the movement has carved its values into the fabric of contemporary Hong Kong culture.

The adoption of a protest anthem; the sustained local coverage and endless reports of confrontations, on the street, in bars, at university campuses, between pro-Beijing and pro-democracy supporters; and the wide international response – all strengthen the position occupied by protesters as the most significant issue affecting Hong Kong in our times.

Consequently, as the idea that the protests have irrevocably changed the social and political climate of Hong Kong gains traction, it becomes more difficult for the government to achieve a resolution.

The greater threat to the legitimacy of the local and central governments is posed not by noisy, violent, attention-grabbing protesters, but by the portion of the population who think of themselves as pro-democracy.

This includes those who identify as part of the movement even if they disagree with some of the more radical actions committed by demonstrators, or have never physically attended a protest or taken part in social media debate, or breathed a word about their political opinion to others.

These people may not have been among those in attendance of the approximately two million-strong march on June 16. These are the invisible protesters who nevertheless contribute to the cultivation of a Hong Kong identity that aligns broadly with values espoused by the pro-democracy movement. These individuals also contribute to the widening ideological divide between pro-democracy and pro-establishment camps, which define themselves in opposition to each other.

With this in mind, how can the myopic, quick-fix censoring attitude of the central government ever work with these invisible protesters, each of whom has, through the force of ideas, the potential for revolution?

China knows this and fears it intensely, hence the ruthlessness of its crackdown on dissidents. Identity and individual interpretations of Hong Kong as ‘home’ cannot be erased like printed words, or disappear like bodies; identity goes deeper than that. Beyond words, it is preserved and even transmitted through culture. The protests have served to tighten the bonds pro-democracy supporters have attached to their home, bonds that will long outlive the present ‘crisis.’