Keep calm and carry on is the motto of the day. Electioneering has somehow carried on despite the interventions of brick-throwing protesters, barricaded streets, and police riot squads equipped with all the tools of their trade.

To call this a protest election is almost a contradiction in terms. It’s more like trying to impose the normal routines of a civic exercise meant for peacetime use on an open rebellion that will not end, because officials cannot acknowledge the causes and solutions are therefore nowhere in sight.

As of now, just days before the scheduled November 24 District Councils election, final decisions about whether to abort have yet to be made. If the threat of violence is great enough to endanger public safety, the election will be postponed. But in Hong Kong’s current volatile atmosphere, public safety can be endangered as quickly as a flash mob can be created via an instant messaging app.

The upsurge of public anger was provoked by a Hong Kong government attempt, earlier this year, to force passage of an extradition agreement with China through the local legislature. Opposition morphed quickly into a popular protest movement over ongoing intrusions by Beijing into what was supposed to remain Hong Kong’s own spheres of political and legal autonomy.

Community-based councils

The election aims to fill 452 seats on Hong Kong’s 18 District Councils, in the first stage of its 2019-20 election cycle. The territory-wide Legislative Council election will be held next year.

This electoral system is a late colonial creation initiated by the British when they were preparing Hong Kong for its 1997 transition to Chinese rule. The idea was to familiarise citizens with the customs and conventions of universal suffrage elections, which was finally introduced by the colonial government in the 1980s, after decades of dithering and false starts.

The neighbourhood-level constituencies were seen as the first direct links between citizens and the formalities of government, in preparation for the day when all members of Hong Kong’s legislature and its Chief Executive could be directly elected. It was a bold if belated idea and became part of the contract formally agreed to by Beijing in preparation for handover.

Today, the local councils serve mainly as top-down conduits to promote government policies and oversee the provision of local amenities. But they also provide opportunities for politicians to establish themselves from their neighbourhood offices and the local problem-solving they can provide for their constituents.

In this way, the councils have inadvertently become representative of Hong Kong’s main contending political forces, although not in the conventional sense of democratically elected politicians responsible to the people governed.

Due to their superior resources, organisation, and connections, pro-Beijing loyalists and their conservative pro-establishment allies quickly succeeded in putting down roots and establishing themselves at the neighbourhood level. As a result, they now dominate all 18 District Councils and look set to maintain their position on November 24.

Pro-democracy partisans have a chance to win bare majorities on only two councils. These are in Sham Shui Po, one of Hong Kong’s poorest districts, and Shatin, a newly developed suburban town located in the New Territories between urban Hong Kong and the Chinese border.

The contending parties

Initially, during the early post-1997 years, people were perplexed at the way pro-Beijing forces moved in to win community-level elections, taking to the unfamiliar routines like ducks to water. British officials had fretted over the idea of introducing anything so undignified and “un-Chinese” as electioneering into local communities where reserved decorum had always been the mark of authority.

So people wondered how pro-establishment candidates had mastered the election routines faster than their opponents who were, by definition, champions of democracy!

A curious contradiction, but easily explained on closer consideration of its organisational underpinnings. A political party was established in the early 1990s, with Beijing’s encouragement, and has since grown exponentially. Now claiming 42,000 members, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB) is Hong Kong’s largest political party by far – mass-based and with all the organisational discipline of its Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mentor. Despite the latter’s long-standing presence here, it remains “underground” and therefore out-of-sight.

Bolstering the DAB’s strength is the Federation of Trade Unions (FTU). Established in the late 1940s, it now claims over 400,000 affiliated union members, who mobilise at election time. The FTU sponsors its own candidate lists, but careful coordination ensures that DAB and FTU candidates never step on each other’s toes by competing for votes in the same constituencies.

Additionally, friendly united front associations now blanket the territory with members also mobilised to turn out at election time.

The contrast with their opponents is stark. Pro-democracy partisans are represented by multiple groups and parties and therein lies one of their greatest weaknesses. None have more than a few hundred members. The largest and strongest are the middle-class Democratic Party and the lawyer-led Civic Party. The Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood is community-oriented. The League of Social Democrats is a party for old-style radicals, and so on.

But since 2003, a concerted effort has been maintained by Power for Democracy, a long-suffering group that specialises in candidate-coordination. The aim has been to mediate between and among members of the many contending pro-democracy parties whose greatest temptation has been to win name recognition for themselves by contesting elections, regardless of the larger consequences. In contrast, pro-establishment forces, guided by their DAB and FTU organisers, contest elections for only one purpose: to win.

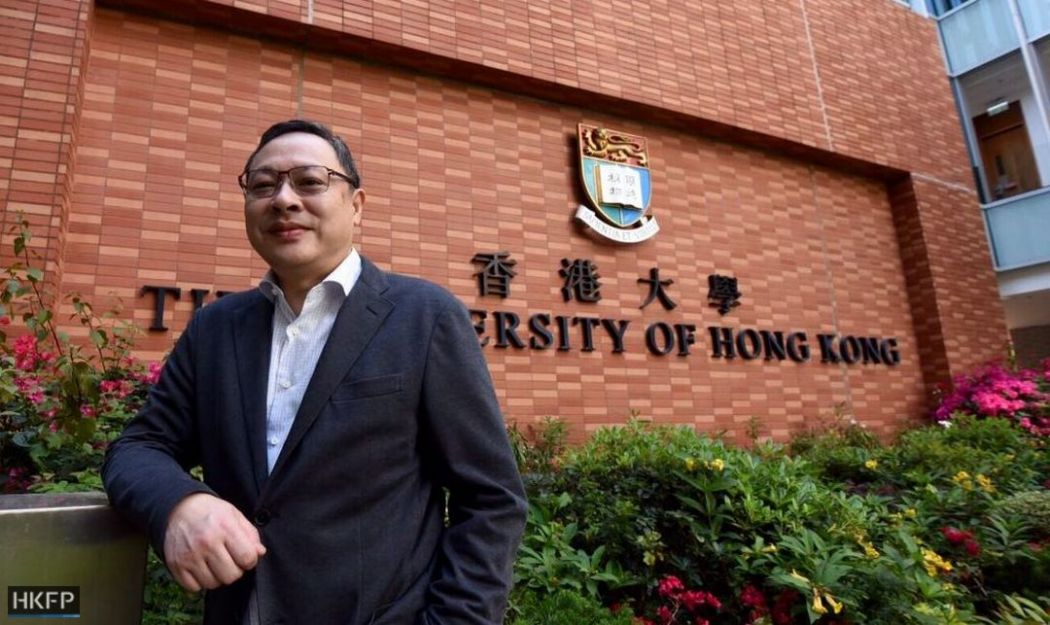

Benny Tai, Project Storm, and the resistance

A major unheralded coordinating influence nevertheless pervades the coming election, along with the upsurge in voter interest and new registrations prompted by the ongoing protest environment.

The man personifying that trend is Benny Tai Yiu-ting, released from prison in August, pending an appeal against his conviction last April on public nuisance charges.

Professor Tai was the originator of the non-violent civil disobedience campaign he and his co-founders named Occupy Central with Love and Peace. It erupted into the 79-day street blockades of 2014. Afterwards, participants renamed their experience the Occupy-Umbrella Movement, from which today’s protests are directly descended.

The aim in 2014 was the same then as it is now, namely, to realise the promise of universal suffrage elections and protest Beijing’s growing interventions. These are gradually redefining the terms of autonomy promised Hong Kong in 1997.

Between Occupy and his 2018 trial, Tai continued as he had been before, coming up with one action plan after another. But his bright ideas during this period all aimed at encouraging democrats to use the existing convoluted electoral system to best advantage despite its defects.

A major goal as he saw it was to maximize fragmented pro-democracy voting strength. For the 2016 Legislative Council election, he came up with a controversial tactical voting plan.

He named his idea for the coming District Councils election Project Storm. Essentially, it meant encouraging democrats to do what they had never done before, namely, to treat the District Councils seriously, as a basic step up the ladder of Hong Kong’s democratic development.

The local councils, he argued, were not only about neighbourhood housekeeping chores, because the councils actually came with some extra inbuilt political powers.

For example, six seats are reserved for District Councillors on Hong Kong’s 70-seat law-making Legislative Council. One of these seats is filled by agreement among the councillors themselves. Candidates for another five seats are nominated by District Councillors from among their own number. But these candidates must then be approved by the public at large on a universal suffrage basis.

Also, 117 seats are reserved for District Councillors on the 1,200-seat Election Committee that selects from among Beijing’s approved nominees to serve as Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. Obviously, more democratic District Councillors mean more democratic influence elsewhere.

This is the ungainly convoluted system that democrats deplore and that has inspired them in their long-running quest for “genuine” universal suffrage elections.

Undeterred, Benny Tai announced his Project Storm idea in 2017. Afterwards, he held countless meetings before the Occupy Nine trial began in late 2018. He was trying to encourage potential candidates to focus on community work well in advance, rather than try to parachute into constituencies as unknown novices at the last minute.

But in one of his letters sent from prison last summer, Tai noted that of the 452 District Council seats to be filled in the coming November election, only about 300 pro-democracy candidates were waiting in the wings, preparing to contest.

Nevertheless, he celebrated the great change he sensed in Hong Kong’s political atmosphere after the massive anti-extradition bill marches in June. He said they were a strike back by Hongkongers against Beijing’s growing intrusions. But he remained committed to elections as the best way of penetrating Hong Kong’s political system.

Since his release from prison in August, there has been little mention of Project Storm by name, or its apprentice candidates. Tai has preferred speaking in more dramatic terms about November 24: as a referendum on the still unfulfilled quest for political reform; as a change election, and on the legal basis for opposing an unconstitutional government.

But the spirit of his plan, in combination with the upsurge of public anger, has had a remarkable unifying effect.

Candidates and campaign strategies

After routine vetting of the original 1,140 hopefuls who submitted their registration papers ahead of the October deadline, 1,090 remain. Hong Kong’s most famous activist, Joshua Wong, was the only candidate disqualified on political grounds.

For the first time ever, a democratic candidate will be competing in all, now 452, constituencies. These keep changing slightly due to population shifts and some questionable boundary changes, in the establishment’s favour, a few years ago.

Power for Democracy has done well on the candidate-coordination front, although a few stubborn holdouts remain in some 30 constituencies.

The holdouts include one veteran who should know better since he has twice been defeated by just such a candidate configuration. Frederick Fung, Hong Kong’s original community organiser, is trying again after losing his long-held District Council seat to the FTU in 2015.

He also contributed to democrats’ loss of their Kowloon West Legislative Council seat in one of last year’s special elections. These were held to replace disqualified Legislative Councillors who were removed from their seats, retroactively and selectively, for loyalty-oath indiscretions.

A few duplicates among pro-establishment candidates have little chance of blunting the well-coordinated DAB-FTU juggernaut.

Given its size, the DAB naturally tops the list with 179 candidates in all. Its FTU ally is sponsoring 62 candidates, with the largest concentration in Hong Kong Island’s Eastern District. This council currently has only five democrats, overshadowed by 12 pro-establishment members.

The most skewed is the Wan Chai District Council, which can currently boast only one democrat. There used to be more but one by one, they gave up trying to compete with the DAB or FTU-dominated pro-establishment coalition.

Pro-democracy candidates will nevertheless be the centre of attention because they represent the “electoral wing” of the current protest upsurge. These candidates will also be the focus of attention because so much effort has gone into compiling the candidate lists and trying to impose discipline on both the candidates and the typically fractious pro-democracy voter base.

As a whole, this base routinely represents over half of the vote in territory-wide Legislative Council elections. But that 50 per cent advantage can evaporate quickly at the district level where the rewards of a few weeks campaigning can seem greater than the neighbourhood-level prize itself.

The pro-democracy camp has united around a list of 396 recommended candidates. They call themselves the Democratic Coalition for the District Councils Election and include people, although not everyone, from old-time pan-democrat moderates to new post-Occupy localists.

All in the new coalition have agreed to support the current protesters’ five demands. One of these has already been achieved: full withdrawal of the government’s extradition bill. Another is the resumption of the universal suffrage political reform project. It was abandoned in 2014 to 2015, after democrats refused to accept Beijing’s mainland-style election design and Beijing refused to budge. The three remaining demands are protest-related.

Far from trying to escape responsibility for the violence and disruption, democrats are running on their record as supporters and frontline mediators between protesters and law enforcement. Pro bono lawyers are in especially great demand given the thousands of protesters now awaiting disposition of the charges laid against them.

Conversely, pro-Beijing forces are running on their record as law and order candidates, and miss no opportunity to label democrats as enablers of the months’ long turmoil.

Nor is it quite accurate to say no one is talking about Benny Tai’s Project Storm. Pro-Beijing paparazzi made a habit of monitoring his meetings in 2017 to 2018, and then publishing the names and photographs of people surreptitiously followed as they came and went.

The practice is continuing as a campaign tactic, matching the old photographs and names with current candidates, tagged for their association with Benny Tai’s effort.

But overall, pro-Beijing candidates are on the defensive, worried about being overwhelmed by the wave of anti-government anger and bracing for unaccustomed defeats.

In contrast, democrats are hoping the wave will benefit them. But they, too, are worried about the potential for a backlash from borderline moderate voters due to the sudden escalation of violence on college campuses in mid-November. This followed the death of a student protest supporter and has turned campuses into battlegrounds during the week before Election Day.

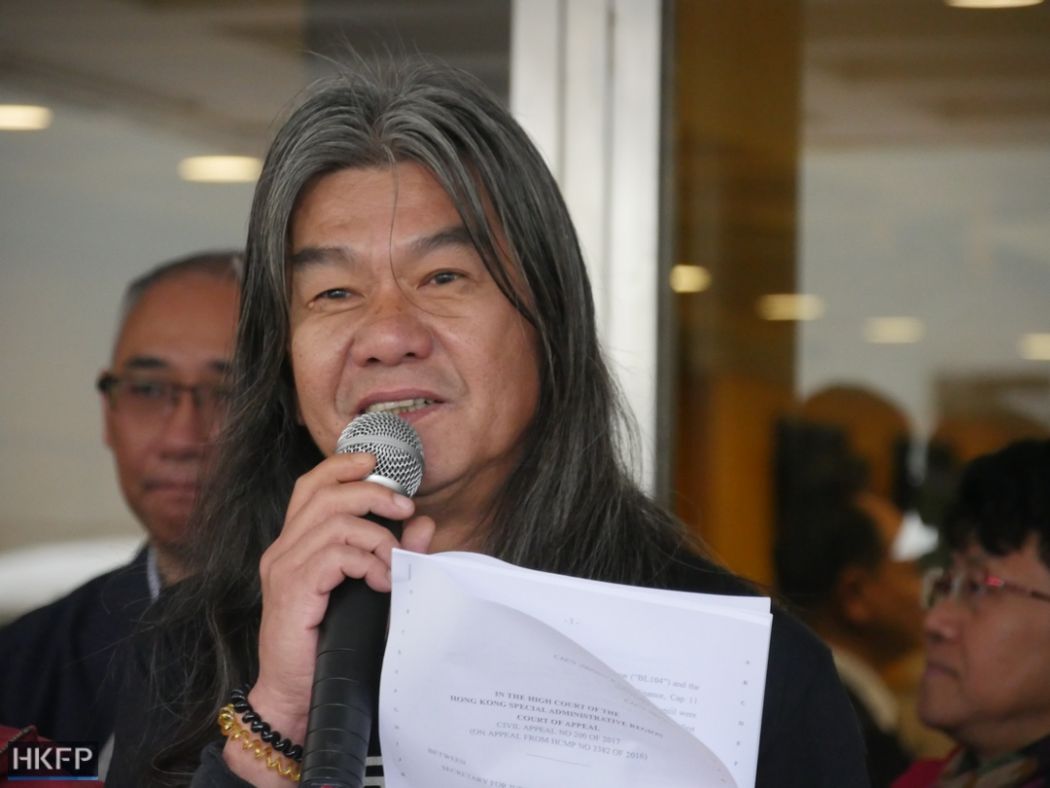

One final note is due to the contribution of an old-time, peaceful, rabble-rouser. With no chance of winning, “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung has nevertheless agreed to help fulfil the challenge of Project Storm by leaving no constituency uncontested.

This he has done by parachuting into the home base constituency of DAB chairwoman Starry Lee. Her supporters can be counted on to rally to her defence, strike a blow for Beijing, and defeat the famous intruder.