Will a national security law be next on the cards, following the extradition bill row? Perhaps not, although probably that sequence was the original intention. This line of thinking follows from two events.

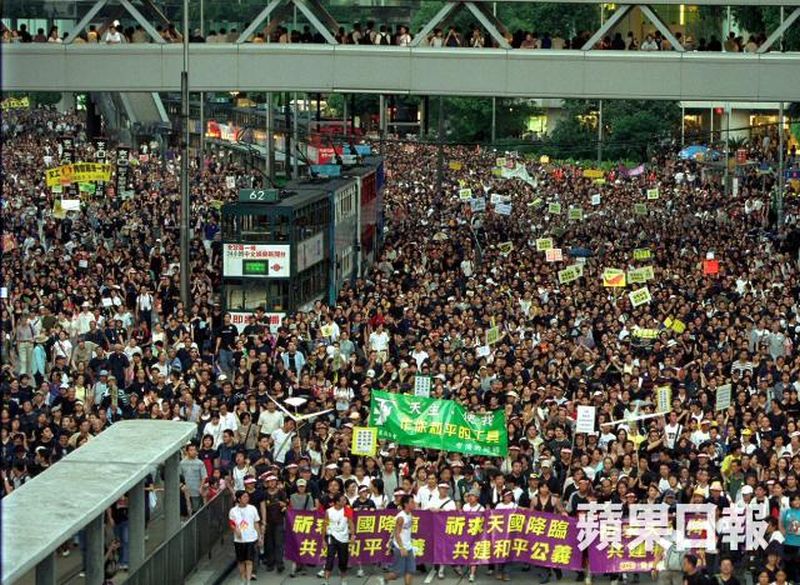

The first was a comment made by Hong Kong’s Chief Executive during a question-and-answer session in the Legislative Council on May 22. The second, on June 9, was the largest protest demonstration Hong Kong has seen since the return to Chinese rule in 1997.

The implications of one follow from the other. Together they suggest that Hong Kong may at least have succeeded in delaying, yet again, the imposition of mainland-style national security strictures on its political way of life.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam figured prominently in both events, along with her insistence on seeing a fugitive extradition bill passed into law by the Legislative Council before the end of this month. The law would permit extradition of criminal suspects on a case-by-case basis to all jurisdictions with which Hong Kong has not yet concluded such formal agreements. Most controversial of those destinations is the Chinese mainland itself, plus Taiwan and Macau.

Hovering over all this was the dreaded national security legislation mandated by Hong Kong’s post-1997 Basic Law constitution. Article 23 stipulates that Hong Kong must pass legislation prohibiting acts of treason against the Central People’s Government, as well as, secession, sedition, subversion, and theft of state secrets. Foreign interference in Hong Kong’s political affairs is also included among the Article 23 prohibitions. Hong Kong is constantly being reminded of its “constitutional duty” to stop procrastinating and pass the legislation.

Laying the groundwork

During the question-and-answer session in the Legislative Council on May 22, Carrie Lam was asked by pro-government legislator Junius Ho Kwan-yiu why her administration was suddenly so keen to pass the fugitive extradition bill, when the matter had been allowed to drift untended for over 20 years, since 1997.

Successive administrations had kept their heads in the sand “ostrich-like,” he said. So why now, when another more important matter had also been left pending since 1997. He was referring to the Article 23 national security legislation. Junius Ho is the pro-establishment camp’s most audacious provocateur and enjoys throwing fat on the fire.

The Chief Executive’s answer provided some fruitful grounds for speculation about her thinking and political strategising. When she took office in 2017, Lam was expected to be a quieter calming influence after the combative style of her predecessor Leung Chun-ying. He is an unabashed pro-Beijing patriot. She is an a-political civil servant, trained in pre-1997 colonial days to obey orders from above and see to it that they are carried out by those below.

The entire range of political debate on the merits of dictatorship and democracy seem to be outside the realm of her interest or experience. Hence her determination to carry out the tasks assigned to her by Beijing, regardless of the political consequences here.

She answered the question by saying, as she had many times previously, that favourable conditions are needed before the Article 23 mandate can be addressed. She then went on to reveal that from the time she took office until now, she had been striving to create such conditions. But “unfortunately, this objective is moving further and further away.”

Of course, like everyone else in Hong Kong, her questioner knows very well why the Article 23 mandate has been left to languish. An attempt to push through the legislation in 2003, similar to Carrie Lam’s current effort over the fugitive rendition bill, led to a massive public backlash.

It was estimated at the time that half-a-million angry people turned out on July 1, 2003 to protest the national security bill, causing James Tien’s Liberal Party legislators to have second thoughts and withdraw their support. Without the votes needed to pass, the bill had to be put on the shelf where it remains to this day, for fear of provoking another upsurge of dissent.

Lam’s answer to the May 22 question reflected that experience when she said favourable conditions were needed before another attempt could be made to legislate on the Article 23 prohibitions. But when she said that despite her best efforts, the favourable conditions were slipping further and further away, she was speaking within the immediate context of the uproar she herself has caused with the drive she launched last February to fast-track the fugitive extradition bill.

So, the obvious question is how could Lam have reasoned that she was doing everything possible to create “favourable conditions,” even as she went about tirelessly promoting an extradition bill that encountered widespread resistance from the start?

Evidently, she and those she has appointed to advise her were oblivious to the endemic fears the new law would provoke. That’s why all the early reporting reflected their surprise, calling the pushback “unexpected.”

But the bill was so carelessly drafted that it has had to be watered down twice just to quiet the nerves of those with direct cross-border interests and connections who are most immediately at risk. Then, with those concessions made and the business community apparently mollified, Carrie Lam seemed to assume the problem had been solved.

She and her team of officials disregarded the possibility of provoking the same deep-seated fear of extending Beijing-style law enforcement into Hong Kong that had provoked the uprising of resistance against national security legislation in 2003.

Doubts and fears derive from the well-known features of China’s Communist Party-led legal system and the anomaly of those who might be returned by Hong Kong’s “independent” authorities, only to face justice on the mainland side of the “one-country, two-systems” fault line.

These fears were ostensibly addressed by writing many safeguards into the bill. These look good on paper but cannot guarantee a fair trial and humane punishment for any criminal suspect once transferred into the hands of mainland legal authorities.

Another unacknowledged lapse is the contradiction inherent in one of the safeguards, namely, that a suspect will not be extradited for an act that is not a crime here. But the impending Article 23 “Sword of Damocles,” hanging over Hong Kong’s head raises the prospect of eventual extradition on national security grounds as well.

All these uncertainties are illustrated in the case of Lam Wing-kee, one of the Hong Kongers caught up in the Causeway Bay Books case. Having eluded his mainland captors once, knowing he is on their wanted list, and assuming the extradition law will be passed, he has just left Hong Kong for Taiwan.

A local pro-government champion of the bill mocked Lam saying he should know he is not at risk because selling books banned in China is not a crime here. But she has no way of knowing what the mainland charges are in his case.

Causeway Bay Books specialised in gossipy titles about mainland leaders, including Chairman Xi Jinping himself. Irreverence on that level carries all kinds of dangerous national security implications, which Lam Wing-kee knows well because he was forced to spend a considerable period of time, incommunicado and without legal representation, as a “guest” of mainland interrogators.

‘Favourable’ conditions

In fact, according to the standards of accountability to Beijing she governs by, there were good reasons for Carrie Lam to disregard the possibility of resistance. This is because since taking office in 2017, she had been so successful in carrying forward the political strategy of her abrasive predecessor Leung Chun-ying. The aim then had been to diminish the strength and credibility of Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Her a-political style seemed better suited to the task than his transparent antagonism.

Together with her Justice Department, exercising its powers of prosecutorial discretion, and judicial deference, Lam’s administration had succeeded in fulfilling Beijing’s mandates with selectively targeted precision.

The 2016 election of six Legislative Councilors was nullified via the oath-taking saga. Several election candidates were disqualified due to their political advocacies. One political party was banned as a security risk and a foreign correspondent was expelled from Hong Kong for giving the party’s leader a public platform to advertise his views.

Numerous activists were jailed in the aftermath of Hong Kong’s 2014 Occupy-Umbrella Movement protests, which followed Beijing’s rejection of all popular Hong Kong proposals for electoral reform. As Chief Secretary, or Number Two in the Hong Kong government at that time, Carrie Lam had overseen the exercise from start to finish with expressionless efficiency.

Most recently nine of the Occupy movement’s most prominent leaders were convicted on public nuisance charges. Four are now serving prison sentences including two university professors and a Legislative Councilor.

So effective has this official strategy been, in further fragmenting and demoralising Hong Kong’s democracy movement, that its candidates actually lost two of the special elections held to replace their disqualified Legislative Councillors.

It followed that these losses strengthened pro-government forces in the Legislative Council, allowing them to revise its rules of procedure and further reduce democrats’ ability to obstruct, thereby making it that much easier to pass the government’s contentious legislative agenda.

Meanwhile, Carrie Lam has been a regular on the commuter flights to Beijing where officials have spent most of the past year on a major publicity drive advertising their latest cross-border integration plan.

This aims to further coordinate economic development in the Greater Bay Area Pearl River Delta cities of which Hong Kong is one. Hong Kongers and especially the younger generation are constantly being urged to investigate the career opportunities that will be emerging from this ambitious new cross-border development project.

National security law next?

All this had been accomplished on Carrie Lam’s watch. Under the circumstances, and with Beijing’s well-publicised encouragement at every step, she might well have concluded, before introduced her new extradition bill, that the way ahead was clearing and she was on course for more victories to come.

The fugitive extradition project followed in direct succession from all that had gone before. The bill was introduced in February. No formal public consultation period was allowed. The standard Bills Committee vetting process was abandoned after the weakened pro-democracy caucus had exhausted its few remaining options for obstruction and delay.

Had it all gone as smoothly as Lam apparently anticipated at the start, she could have felt confident that she had succeeded in creating the conditions needed to pursue the ultimate, Article 23, challenge.

But insensitive to the politics of dissent as she is, Lam also seems to have overlooked the implications of her extradition law for all the cross-border projects being championed as an outlet for Hong Kong’s disaffected youth seeking job opportunities and a prosperous future.

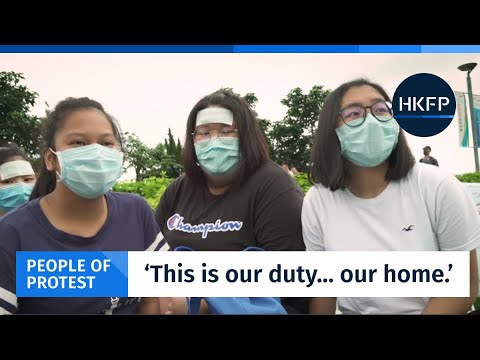

Those cross-border opportunities also contain the traps of an unfamiliar legal system and now Hong Kongers are being told that flight back home to Hong Kong in case of trouble will not protect them. So, no wonder it suddenly seems as if Carrie Lam’s extradition bill has given birth to a whole new generation of Hong Kong protesters.

There were many gray-haired old-timers in the marching lanes on Sunday June 9. But another overwhelming impression, beyond the sheer size of the crowd, was its youth. Young Hong Kong was everywhere, in white T-shirts and Bermuda shorts, the dress code of choice for a sweltering summer marching day.

In fact, no one, not even the organisers themselves, anticipated that the public would respond on June 9 in another 2003-style angry mass uprising. Then, in 2003, it was the national security law. Now the fear is rendition into the hands of mainland law enforcement authorities.

The protests are continuing. There is talk of a general strike, unheard of in contemporary Hong Kong, as well as classroom boycotts, and a mass rally surrounding the Legislative Council building, just like the protest planned after the July First march in 2003.

The situation is comparable to the days just after July 1, 2003, when the Tung Chee-hwa administration dug in its heels and refused to withdraw its legislation. But that was before James Tien and his Liberal Party legislators announced their decision to withdraw support for the bill. Whether that sequence can be repeated now is uncertain.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam has made one thing clear. The ultimate Article 23 prize for Hong Kong Chief Executives is now moving further and further away, probably more like becoming a poisoned chalice for all who follow her.

The Hong Kong Free Press #PressForFreedom 2019 Funding Drive seeks to raise HK$1.2m to support our non-profit newsroom and dedicated team of multi-media, multi-lingual reporters. HKFP is backed by readers, run by journalists and is immune to political and commercial pressure. This year’s critical fundraiser will provide us with the essential funds to continue our work into next year.