Thirty years ago on June 4, I sat around a small television screen at my grandmothers home in Hong Kong. I was nine years old. My grandmother sat closest to the television, on a small plastic stool. All of my family in Hong Kong were there in that room, in front of that small screen. I sat cross-legged on the floor, beside my mother, who held me firmly. As we watched I felt her grip tighten. At several points she embraced and kissed me, and I felt her tears on my cheek.

Usually, on a Sunday I would have been at the Club swimming with friends, or running barefoot across the cricket ground. My family, as Eurasians, shared many of the trappings of expatriate life. We spent holidays abroad, and had a holiday house on Lantau island’s south coast.

But we were also different. My family had come to Hong Kong as refugees several generations back. We were never people in transit. Hong Kong and China represented more than just the present: it was also our past. We identified as a part of China, as Chinese, and this was our home.

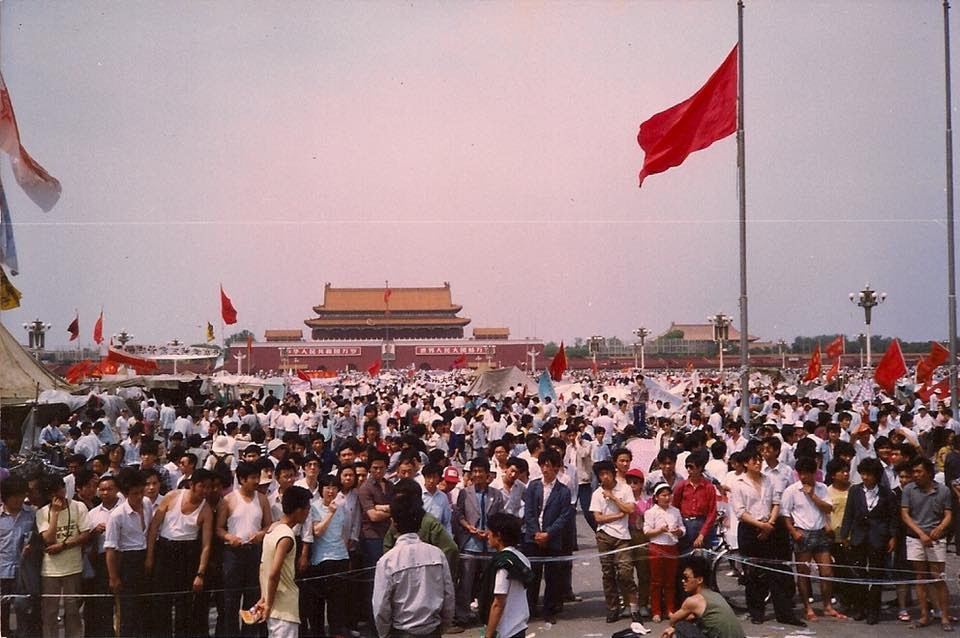

From April 1989 all of Hong Kong watched, with increasing hope but also unease, as a memorial in Tiananmen Square in Beijing to the late Hu Yaobang, the reformist General Secretary ousted in the “struggle against bourgeois liberalisation” two years prior, evolved into mass demonstrations around the country demanding for political reform. During these weeks I returned home each day from school to find my family following closely each development. The BBC world service replaced Phil Collins on the radio. I recall watching on the television images of young people with headbands laying wreaths next to a black and white portrait.

I had never been to Beijing, nor did I know who the man in the portrait was nor why there were demonstrations; nor could I understand anything of what was being said, as – like all of my family – we only spoke Cantonese. However, even as a child, I could sense something momentous was happening, as everyone, everywhere in Hong Kong seemed to be gripped by the events. But most of all I felt its importance within my own family.

Like many families in Hong Kong, our identities are complex. We had all been raised as British subjects, but we identified as a Chinese family; one of my aunties was married to a staunch Communist, another had married a Nationalist. Several relatives had “moved away” and now lived in the US; others had “remained” and had been born and lived on the Mainland. My mother had married into an English family, and I had been raised in Hong Kong as an English boy. However the thought of boarding school in England, as was expected, frightened me, and I choose against this path. I was not English, nor was nor could I be, I thought, England.

The 1989 demonstrations struck a nerve buried deep within my family. Arguments became more common, especially among my younger uncles in whom age had not yet tempered their political conviction. As the weeks passed and neither the government nor the protestors would back down, tensions only heightened. One uncle laughed and shook his head dismissively, complaining the students were merely causing a nuisance and that this was not the way to act. I always remember an answer he gave to me then when I asked, in English, what the protests were about: “they [the protestors] are stupid,” was all he said.

On June 4th, as images were broadcast across our screens and began to fill our heads my family seemed to shut down. All arguments ended. At one point my youngest uncle began to punch the wall. He continued for some time until my grandmother stopped him. I remember seeing his bruised hands. They remained clenched.

My grandmother had lived through the Japanese occupation and the death of her husband and my grandfather. She had a steel about her — an emotional numbness. Later I would discover much of her family had been murdered by the Communists and that she hated them. Yet she said not a word, least to my uncles who forever sung the praises of the Communist Party. Fear, as I would learn, often outweighs hatred.

Lu Xun, arguably the greatest Chinese writer of the 20th century, described “the state of numbness,” as necessary when the only alternative is “increased suffering and pain,” and when even “hope for the future” brings little comfort. Still, my grandmother cried that Sunday. We all cried.

On that day, I cried as a child. I sensed the distress, the pain and the hurt. There were other emotions I could not understand and so could not feel: of shock, grief, fear, panic, anger and rage. However I knew what I was feeling and what I was witnessing happen on screen was profoundly wrong. The shaky clips and noise, and the voices, the shouting and the crying, all carried with them a resonance. That day I felt how deep my Chinese roots lie, but also how much different a China existed in Hong Kong. June 4th taught me, before I even knew of or cared for politics, that a nation and a people are not defined by a government, let alone by one party.

Since that day, I have carried a pain. It is a pain ever one in my family carries, and a pain, I am sure, that is carried by those generations of Chinese who remember. In Hong Kong we watched from afar, but still our hearts stopped. No one in my family was at any of the demonstrations that day, nor was anyone my family then knew. And still my grandmother cried. Did it mark the extinction of a China dream and the beginning of a nightmare — a point at which any genuine hope for reform within China was extinguished? No one in my family, even my Communist Party-praising uncle, trusted the party. It came as little surprise that within two years, and despite British assurances, my parents and my siblings would be the only members of our family still in Hong Kong.

The pain continues in our hearts because the Communist Party refuses to acknowledge what really happened. It is a truth recorded not only in the dead, but in the memories of the living that cannot be erased. There was no foreign conspiracy, no imminent threat. By continuing to deny the massacre that took place that day in 1989, the Chinese will never find peace and China will never be either harmonious nor stable.

To quote someone who was there, and who never forgave himself for a moment of cowardice in later life when under duress he lied against his conscience:

In the depth of despair

remembering the dead

is the only hope. May darkness transform into stones

scattered across the wilderness of my memory.

Twenty-eight years, later Liu Xiaobo would die in state custody, a political prisoner, the better known or the tens of thousands of named prisoners of their own memory, and tens of thousands more who died nameless.

Despite the best attempts of the Communist Party, the Chinese have not forgotten June 4th. We must not forget those that died that day, and the events that traumatised a people. Let us carry forward with us the one hope of everyone at Tiananmen that day, and watching around the world, that China and the Chinese people may one day live lives free of the yoke of oppression, free from fear and united by a shared dignity.

Kong Tsung-gan‘s new collection of essays – narrative, journalistic, documentary, analytical, polemical, and philosophical – trace the fast-paced, often bewildering developments in Hong Kong since the 2014 Umbrella Movement. As Long As There Is Resistance, There Is Hope is available exclusively through HKFP with a min. HK$200 donation. Thanks to the kindness of the author, 100 per cent of your payment will go to HKFP’s critical 2019 #PressForFreedom Funding Drive.