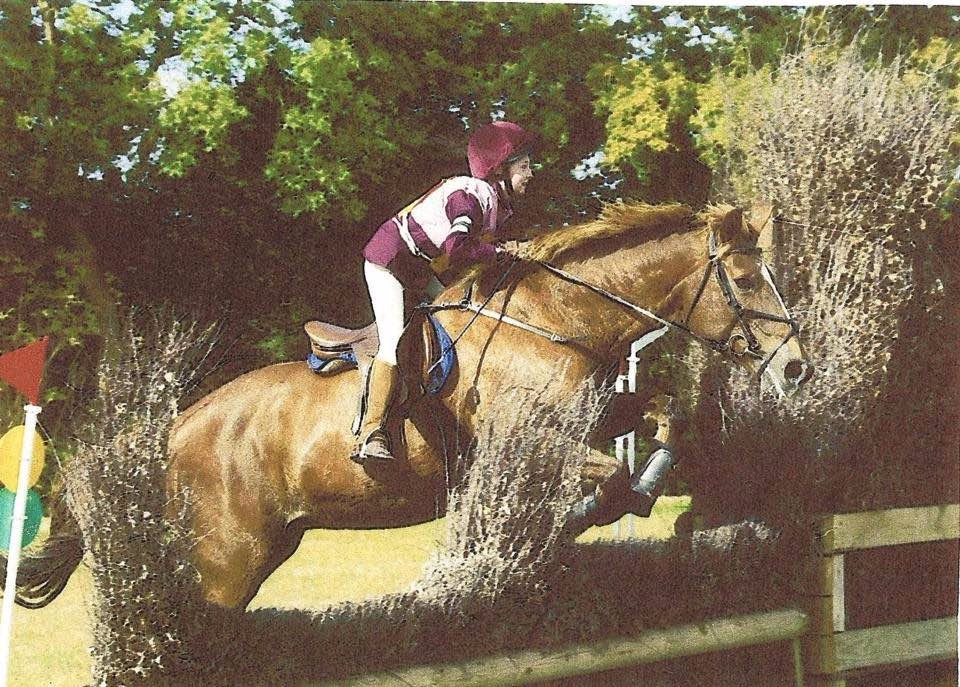

Bobbie Poulton grew up surrounded by horses on a rather remote farm in the English countryside bordering Wales. Learning to ride before she could walk, she became involved in competitive shows from an early age, through which she learnt the thrill of dedicating oneself to achieving excellence in a very physical, and rather solitary, skill.

“I love the feeling of being the best, just for me, me against me, that’s what I love. It doesn’t matter how good your opponent is, you can’t control anyone else,” she tells HKFP. “I can’t control anyone, I just know that I have to give it my absolute best. I love giving 100 per cent.”

Bobbie’s indomitable spirit has seen her rise through the ranks of Hong Kong’s gruelling CrossFit circuit and push herself well past her limits. But also seen her through a life-shattering injury and its painstaking recovery.

At 28 years old, Bobbie has found herself in Hong Kong, where life and its pace are nothing like rural Britain. She arrived in 2012 with only a rucksack on her back, some savings in her pocket, and with the aim of moving to Auckland, where she had been promised an internship in sports therapy.

But, seven years on, she ended up staying in the city. By this point, Bobbie had grown up, found passions besides horse-riding and gained a degree in sports conditioning and rehabilitation in Cardiff – the Welsh capital. She had also found herself to be good at rugby, enjoying the intense physicality of the sport. Nevertheless, she found the pressures of operating within a team rather stressful.

“I don’t like letting people down,” she says. “I put a lot of pressure on myself.”

A new era for Hong Kong’s fitness industry

Growing up surrounded by men, her father being her best friend, Bobbie never felt much stigma when it came for opting for more “masculine” hobbies. She studied rugby at college, on a course in which she was the only girl – not that she minded. And when the opportunity came to pick up and study the science of weightlifting while at Cardiff Metropolitan University, she lept at it.

“I remember walking into the gym, and I saw the lecturer, Jeremy Moody, do a single arm barbell snatch – that’s proper Olympic lifting, a really hard manoeuvre. And that was that, I was hooked” she says. “It seemed really technical, and really empowering”.

Bobbie was somewhat ahead of the curve at the time, but more and more women are getting into weightlifting in a big way, in the West as in Hong Kong. Weightlifting and Crossfit gyms have mushroomed across the city, some geared exclusively to women.

The Hong Kong fitness industry used to – and still does in some areas – operate under the idea that a cardio-stricken female body that starves itself is “healthy” and “attractive.” And that women lifting heavy weights would “bulk up.”

It is only now starting to adapt to the reality that women’s bodies benefit as much from building muscle as men’s. And in gyms all over Hong Kong, the squat rack is no longer the preserve of that bulky guy you’re too scared to look in the eye.

One keen observer of the trend is Hong Kong’s Tricia Yap who has, for years, been advocating the health benefits of lifting and resistance training for women in a city that still places far too much value on “smallness” as a desirable feminine trait.

The trailblazing fitness entrepreneur and coach, who also lays claim to the title of the city’s first female MMA fighter, has a nuanced take on the rise of female weightlifting in Hong Kong, and related trends like CrossFit – which inspires many to push their body to the limit.

“I love that women are now encouraged to lift weights and that the athletic body is starting to be celebrated,” she told HKFP.

“But whether the societal pressure is to be supermodel-skinny or have muscular curves, the dangers of body image still remain the same – some women are willing to go to extremes to achieve either look quickly, because they want results immediately and forget about balancing aesthetics, performance and health.”

The industry has ballooned since she started her first fitness venture, Bikini fit, in 2012, later opening lifting and boxing gym, Warrior Academy. But she is concerned it is now “scarily under-regulated.”

CrossFit games: ‘Who is better at gym?’

Bobbie’s passion for weightlifting travelled with her to Hong Kong. After getting involved in the rugby team, and coming close to competing for the city, she found her way into the world of competitive CrossFit.

The sports regimen and related contests have exploded in popularity since the brand was founded in 2000 in Santa Cruz by Greg Glassman. Glassman is said to have developed the programme in his garage as a teenager, having been determined to build physical strength having contracted polio as a baby. He is known for his brashness and his libertarian philosophy.

The CrossFit regimen brings together Olympic lifting, gymnastics, high intensity, interval training and other challenging disciplines. Bobbie describes it as “constantly varied functional movement that serves as a catalyst for moving and feeling better,” and coaches a version that takes into account the specific abilities and limitations of each individual, in a sustainable way.

At its extreme end, which finds expression in the CrossFit games, athletes learn to perform mindboggling feats of strength and endurance. Sift through some of the social media output on the world’s “fittest men and women” and you will see incredibly shredded bodies performing mesmerizing things.

“What you see on Instagram, those super-jacked people, that’s not the reality,” Bobbie says.

Bobbie threw herself into CrossFit, all whilst working as a fitness trainer, which comes with its own set of pressures and demands.

“Being in this industry, there’s this pressure to be a certain way, move in a certain way, to represent health. We’re supposed to be walking symbols of health and wellness,” she says.

It’s a pressure Tricia Yap, who a few months ago had a child, agrees is pervasive throughout the industry.

“There’s lots of pressure to look good. The number of times I’ve been asked why my abs aren’t back… um, my baby is four months old?! It takes two years hormonally to recover from childbirth,” Yap says.

In the world of competitive CrossFit, Bobbie rose up the ranks to be placed fourteen out of 3000 in 2017. That was out of the entire Asia region, including Russia. She placed third in Hong Kong. That year, she was offered a spot to represent Asia in the Pacific region, in a contest taking place in Australia.

“CrossFit is basically competing at ‘who is better at gym,’ she says. “And to be the best at anything is not healthy. It comes with risks.”

Bobbie resolved to give training for regionals her all, pencilling in three hours a day to put her body through gruelling workouts while treating her nutrition with the exactitude expected of professional athletes.

“I wanted to compete against the big dogs, full-time.”

‘From that day on, it was game over’

In her athletic element, Bobbie’s lifting stunts were impressive by any margin. At 5’3 and weighing 53kg, she could clean and jerk 95kg, which is an intricate, powerful set of manoeuvres in which one swiftly lifts a barbell from the ground over one’s head, lands with one’s feet apart, and then lands again with the feet and torso aligned as the barbell remains hoisted above one’s head with straight arms.

“It comes down to my personality. I was driven, I like to take risks,” she said. “… And getting to regionals was the only time I’d really been proud of myself. Apart from getting my degree.” she added. “All I cared about was my athletic identity”.

Bobbie didn’t know at the time that she has a congenital disorder called Ankylosing Spondylitis, most likely inherited through her mother’s side, who has Crohn’s disease. It is a type of arthritis that causes an inflammation of the joints, fusing the spine’s bones together, which make it very vulnerable to injury.

One afternoon in June last year, Bobbie caught a barbell, felt a click in her spine, and fell to the floor. Reeling from pain, she went to the hospital, had an MRI scan – but no X-ray – and was told that she most likely had a bulged disk.

“That’s not too scary,” she thought, and loaded up on painkillers as she flew out to Australia to train and compete. What she didn’t know, as she was labouring away, was that she had three fractures above her spine. She returned to Hong Kong having put her body through such duress that she could not walk without discomfort.

She took a bit of time off and returned to the gym in August.

“…and there I was, Bobbie loads up and puts a bar on her back… and I felt a shift in my spine – the whole vertebrae shifted — and it was game over,” she says. “From that day on, my life was never the same again”.

‘The old Bobbie is gone, and she’s never coming back’

Besides being a top-notch athlete, Bobbie likes to feel positive and to make people happy. And she doesn’t like to ask for help. From that day on, all of those qualities that had made her who she was became a challenge for her to hold on to. “It felt like I lost my identity,” she says.

“I had 9 /10 pain every day, I couldn’t work, I would lie and smile, put on my ‘happy’ smile, but inside I was dying,” she said.

It quickly became clear that she needed surgery. The procedure, an anterior lumbar inter-body fusion, would involve pulling the spine together with the help of a bone graft. Surgeons would have to cut through muscle tissue, either through the back, which is the safer option or through the front, which, though higher risk, would enable Bobbie to return to training faster.

She insisted on surgery through the front, despite being advised otherwise. “My only goal was to get back to competing, that was my self-worth. I was willing to risk even my health to get back there,” she recalls. “I thought, if I die on this table… well, what have I got to lose?”

It’s been over a year now since the surgery, which took place on November 14, at a public hospital in Chai Wan. Bobbie recalls waking up in the worst pain she has ever endured, with her stomach cut open, unable to move, feeling utterly helpless. It would be three days before she could move her head.

After a week she was sent home in crutches and a metal corset she would have to wear for the next three months. Loaded up on painkillers she was allergic to, which she violently threw up, Bobbie was told not to move at all.

That spark of life

Enthusiastic well-wishers told Bobbie she would soon be back “stronger than ever.” She expressed gratitude about the support network she had around her, including her boyfriend at the time who served as her full-time carer, and a good number of devoted friends. The journey to recovery was long, excruciating, arduous, and filled with feelings she struggled to accept in herself.

“I felt crushed, and continued to feel crushed. My confidence disappeared. I couldn’t give myself a break, I was so hard on myself,” she recalls. “I felt ashamed.”

Bobbie defied various odds through recovery, owing to her own stubborn resolve to do whatever exercise she could, against doctor’s orders, and based on her own understanding of the human body and its ability to heal.

“We need stress to create adaptation, physically, and mentally,” she says. It started with simple breathing exercises, to gentle core work, to eventually leaning against the wall, to doing the odd press up, later chin-ups and lunges. She would go to the gym with her metal corset hidden under her shirt.

Come March, Bobbie would be in the hospital again and was told that she was recovering well. A few months later, she would be lifting heavier and heavier weights, and was even considering getting back into competing-mode despite the potential havoc this could wreak on her still-recovering body.

But something in Bobbie had changed. Still struggling with self-esteem, she removed herself from certain circles, switching off certain social media channels that are riddled with outlandish imagery on how the body should look and what it can accomplish.

She quit her job, struggling to train people to be strong and feel great when she felt she embodied neither of those things at the time. Unlike before her accident, she struggled to share in other people’s joy as their strength and fitness improved. She noticed cellulite on her legs, and recoiled.

It took time, but gradually, incrementally, she softened, grew kinder to herself, and grew into a different kind of strength.

“I realised that I was living this lie, I was in this shadow… trying to be the old Bobbie,” she says. “And I’m still battling demons, but I’ve stopped comparing myself to others, and I went back to being a normal person”.

Bobbie still loves to work out. You’ll find her at the gym at 5am every morning, putting herself through various paces, with a look of determination on her face that is quite different from her usual, smiley-coach demeanour. Sometimes, she’ll jump up on a bar fixed to the wall above, and perform a series of kips and chin ups. Feats that would have been absolutely impossible for Bobbie to do this time last year.

To the uninitiated, these gymnastic feats involve pulling your body up, and in the latter move, swinging powerfully as you do so. They are some of the movements those newly initiated to the world of CrossFit and its various offshoots find themselves staring at in awe. For all CrossFit’s health hazards, it is a space in which one can really marvel at what the body is capable of when it is put through certain rigours.

Bobbie is devoted to working out and challenging her body because it makes her happy. But she avoids the gyms that offer “false hope,” and promote unhealthy ideals. Like Tricia Yap, she worries about the lack of regulation, and the rate at which new gyms spring up, many of which with coaches who, as Yap describes, might have no more than three day’s worth of training.

Bobbie is starting her own business, Transcend Performance, which aims to foster good, sustainable health in a city that can grind you down.

“In Hong Kong, it’s the stresses, pressures, the crush-you-down-ness, the way we all live like lemmings in shoeboxes. It’s what makes you give your 100 per cent when you find something special. That spark of life,” she says. “For me, that was CrossFit.”