For sure, it’s at least a matter of public perception. Those who speak in the judges’ defence are forever protesting their innocence: independence intact, never compromised despite the challenges, Lady Justice continues to reign supreme from her perch atop the Central court building, and so on.

But something must be wrong if middle-aged university professors can be overheard muttering in stage whispers “they’ve been bought” of the judges, and “ridiculous” about their rulings.

These mutterings and much more have been provoked by a series of recent court rulings, all with political implications: the retroactive disqualification and removal, for improper oath-taking, of six Legislative Councillors duly elected in 2016; the re-sentencing and subsequent imprisonment of student leaders for their role in precipitating the 2014 Occupy Movement; the disqualification of prospective candidates ahead of the 2016 election; and the stiff prison sentence handed down last month for a young politician convicted of rioting.

This ongoing sequence, with more trials in the pipeline, has been accorded all the formalities of due process: multiple court hearings, arguments, rulings, and appeal judgements. But the sequence has also had the effect of targeting … for all to see and with some key questions left unanswered … the most promising leaders of Hong Kong’s latest political generation.

This generation came of political age during the long campaign for universal suffrage elections that culminated in the 2014 Occupy Movement. Major city thoroughfares were blockaded by protesters for 79 days, beginning in late September 2014.

Such elections had been the goal of Hong Kong’s democracy movement since the 1990s when they became one of many promises made by Chinese government officials in preparation for the 1997 transfer of Hong Kong from British colonial to Chinese rule.

Protesters moved out onto the streets in 2014, once Chinese officials finally began to come clean after years of procrastination and euphemistic generalities. As it has turned out, Western-style open elections, and the official Chinese definition of universal suffrage, are two very different things. So is the promised “autonomy” — that was going to allow Hong Kongers to manage their own affairs — by comparison with the reality of post-1997 political life.

Those distinctions might have been acknowledged by British and Chinese negotiators and written into the original pre-1997 promises. But for whatever reason there were no definitions, so the public was not forewarned. Everyone has had to “learn by doing,” one step at a time, from one year to the next.

Today, the consequences of that disconnect … between pre-1997 promises and post-1997 Chinese mandates … are finally playing themselves out in the form of prison sentences, blighted careers, unfulfilled expectations, and new demands for autonomy of a kind that might realize the pre-1997 promises as people here originally understood them.

Those demands are also now coming, most insistently, from members of the younger generation who have grown up and come of political age during the years since 1997.

Defending law and order

In response, the authorities still have little to say beyond blaming the critics. Hong Kong’s new Chief Executive Carrie Lam, who replaced the much-disliked Leung Chun-ying just one year ago, has led the way with a one-dimensional defence of her Justice Department.

Addressing widespread criticism of the six-year prison sentence imposed on 27-year-old autonomy-independence advocate Edward Leung Tin-kei, Lam said it is actually the critics who are undermining Hong Kong’s reputation for law and order. She said it’s wrong for people to criticize the law just because they disagree with a verdict.

Lam was defending the way the Justice Department had prosecuted Leung and others for the 2016 Lunar New Year mob violence in Mong Kok. It’s OK to criticize, she said, but not to suspect the motives of the prosecution and sentencing guidelines. She therefore concluded that it was the critics who were politicised, not Hong Kong’s legal system.

She made the same accusation last year when critics here and elsewhere protested the re-sentencing and jail terms for student leaders Joshua Wong, Nathan Law, and Alex Chow. Heralded as Hong Kong’s “first political prisoners,” they had already completed their community service sentences for actions that precipitated the Occupy street blockades in September 2014.

Lam said such accusations were irresponsible and groundless. They could damage the very foundations of Hong Kong’s success, foundations that had been built on its reputation for maintaining an independent judiciary that upholds the rule of law for all alike.

Among the distinguished legal personalities who spoke out in similar terms were former Court of Final Appeal judge Henry Litton, former director of public prosecution Grenville Cross, and barrister Ronny Tong, formerly of the pro-democracy Civic Party.

Litton said Hong Kong’s judicial independence was alive and well. He also said the additional prison sentences for the three student leaders was not a case of double jeopardy. The new sentences were entirely appropriate because their actions had involved violence.

Grenville Cross wrote that Hong Kong is “blessed with a legal system which is effective, open and just.” He also emphasized Hong Kong’s “prosecutorial independence” and noted that prosecutions are meticulously prepared. So much so that cases brought before the High Court have a 90+% conviction rate.

He dismissed as “ill-informed” recent criticism of the judiciary for verdicts and sentencing in sensitive cases. Rioters were receiving their just deserts and in any case they could always appeal.

Ronny Tong, now a member of Carrie Lam’s Executive Council cabinet, reworked her argument and ended with a dramatic flourish. His foil was Hong Kong’s last British governor Christopher Patten who had spoken out against Edward Leung’s six-year prison sentence. A jury found him guilty on one count of rioting, but not on a second charge of incitement. Prosecutors are reportedly considering a re-trial in hopes of securing a stronger conviction.

Patten suggested it was an excessively harsh sentence and an abuse of Hong Kong’s Public Order Ordinance, which his administration had tried to modernize before 1997. He was quoted as saying the old colonial law remains vaguely worded and ‘is now being used politically to place extreme sentences on democrats and other activists‘.

Tong ridiculed Patten for defaming judge and jury in the rioting case and mocked people like him who are “running our rule of law into the ground.” Democracy could not survive in an environment where politicians are allowed to abuse their monopoly in shaping public opinion.

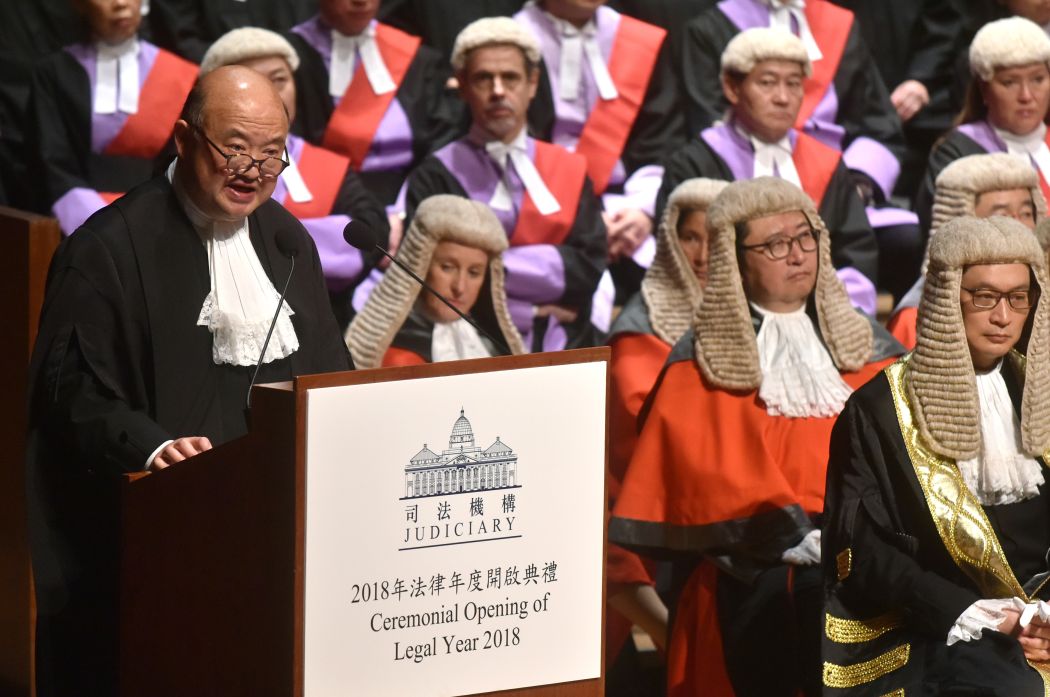

A more judicious defence, by Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma

The people closest to this storm are, of course, duty bound to remain silent … with a few exceptions. Most important of the exceptions is Hong Kong’s Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li, whose infrequent words on formal occasions are followed attentively. One such occasion is the ceremonial opening of each legal year and 2018 was no exception.

Ronny Tong had referenced Chief Justice Ma’s warning last January about the “unwarranted criticisms” being leveled against Hong Kong’s rule of law. The Chief Justice had emphasized that Hong Kong’s judiciary is independent, and the courts follow the law, the law alone without any other considerations.

But he said something more … with an explanation of the court’s additional responsibility, especially important for the administration of justice in troubled political times.

He spoke especially about the importance of transparency in the operation of the courts so that the public could be properly informed when commenting on end results. Toward that end he reviewed the basics.

Hong Kong remains a common law jurisdiction as it has been for the past 180 years, he said. This is regarded as the foundation of Hong Kong’s success, not just for the ever-present concerns of business and finance, but for the entire community.

A key feature of the common law, he noted, is its reliance on case law, or the doctrine of following case precedents. Its practical purpose is to make the law predictable so that “one can be assured that similar legal situations will be dealt with in a similar way.” This allows everyone to manage their affairs in a predictable way.

The responsibility of the court in such a system, he continued, is to provide reasoned judgments properly and fully explained, open and accessible to the public. “It is important for everyone to see that applying the law is key and that there are no extraneous factors in arriving at the determination of a legal dispute.” Why and how courts arrive at their decisions must be plain for all to see.

The retrospectivity trap revisited, by “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung and Martin Lee

Chief Justice Ma framed the problem perfectly. If only his judges and their rulings could follow in kind! As it happens, the single greatest source of “unwarranted criticism” during the past two years has been the selective and retroactive disqualification and expulsion from the Legislative Council of six duly elected legislators.

Multiple court decisions have affirmed and reaffirmed the disqualification verdicts. But how they were reached has yet to be made plain for all to see. They have not been adequately explained, which is why … given Beijing’s interventions… widespread suspicion about “extraneous factors” persists.

The question people keep asking is how a common-law system … that respects the principle of precedent and predictability … can impose retroactive verdicts that disqualify legislators for oaths they took that were not illegal at the time they took them. This is not simply a matter of misunderstandings on the part of the general public … whether informed or otherwise.

Even defence lawyers representing the legislators did not understand and were chastised in court for their “ignorance.” But when the Court of Final Appeal issued the final ruling last summer, the judges only cited the precedents that had been cited before … still without explaining in plain language for all to understand.

This episode in Hong Kong’s post-1997 history has become known here as the oath-taking saga. And despite the absolute final verdict from the Court of Final Appeal, the saga remains ongoing.

To re-cap: The Legislative Council election was held on September 4, 2016. The swearing-in ceremony was held on October 12. As many as 15 legislators, among the 70 total, allegedly embellished their oaths of office that day. They did so with various pro-democracy gestures and protest slogans. This provoked central government leaders in Beijing to issue, on November 7, a formal Interpretation of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, Article 104 on oath-taking.

Accordingly, oaths must now be taken word-for-word, solemnly and sincerely. No second chances. But of the 15 who embellished their oaths, only six were prosecuted by Hong Kong’s Justice Department. All six were judged guilty as charged by Hong Kong courts citing, in the first instance, a past Hong Kong precedent and Beijing’s Interpretation of Article 104 thereafter.

The local Hong Kong precedent might have made sense since it involved two legislators who repeated oaths they themselves had drafted. The precedent was set by a 2004 judicial review that ruled against individualized oath-taking.

But the second batch of four legislators had actually been allowed to retake oaths that were deemed problematic at the time and all were formally sworn in. This followed the Legislative Council’s precedent and customary practice that had evolved since 2004.

The precedent dated back to a request by then newly-elected legislator “Long Hair’ Leung Kwok-hung. He wanted to write his own oath but, unlike the novices of 2016, he had the good sense to ask permission first via a judicial review request. The judge said no. So, Leung took the standard oath and shouted his slogans afterward.

This became customary along with the practice of allowing oaths to be re-taken, which is how the four came to be sworn in. They served as legislators for several months before the disqualification verdict was handed down in July 2017. Defence lawyers for the second batch of four legislators focused especially on two questions: the selective nature of their disqualification, and its retrospective aspect.

Justice Thomas Au’s reasoning on the first question was a masterpiece of judicial obfuscation. Presumably, punishing a few to teach the others a lesson is also not a common law principle. But this issue was soon forgotten.

What remains an ongoing source of anger and suspicion is the second question. As Chief Justice Ma noted, common law follows case precedent so that citizens can predict how to regulate their behavior accordingly. Legislators had thus calculated the circumstances in which they would be allowed to re-take their oaths and retain their seats, and they could logically expect to remain seated in them.

But all such arguments were to no avail. In ruling after appeal ruling, Beijing’s November 7 Interpretation of Basic Law Article 104, became “what the law had always been,” dating back to Day One, July 1, 1997.

The answer lies in the distinction between ordinary case law, the subject of Chief Justice Ma’s presentation, and laws passed by legislatures, which he did not address. Common law does follow the retroactivity principle for interpretations of the latter. Which is why the appeal judges kept repeating … “what the law has always been”. But no one has yet troubled to explain that distinction, at least not to the voters who elected the six legislators.

Hong Kong’s Basic Law was adopted by the National People’s Congress in Beijing on April 4, 1990, and went into effect as of July 1, 1997.

Nevertheless, die-hard attempts to escape the retrospectivity trap continue. It is fitting that veteran agitator “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung is seeking redress in this way since he is the pioneer of dissident oath-taking.

His chief counsel is veteran barrister-politician Martin Lee Chu-ming. Both are treated as pariahs by pro-Beijing loyalists and not much better by Hong Kong’s political establishment.

“Long Hair” is the last of the six to persist. The others have either run the gamut of their appeals or given up. He may soon have to do likewise because one of his key manoeuvres has just been torpedoed. Leung and Lee are arguing that Beijing’s November 7 2016 Interpretation of Basic Law Article 104 added many more conditions to the original meaning of Article 104 on oath-taking.

Therefore, Beijing’s Interpretation is actually an amendment to Article 104, not an interpretation. Amendments are processed differently (Basic Law, chapter 8), and would not be subject to retroactive enforcement.

This argument has already been rejected in earlier rulings. But Leung and Lee asked that new evidence be introduced to the same effect by an expert witness in Beijing. After considering a preview of his evidence, however, the court rejected it. In a June 13 ruling, Judge Jeremy Poon announced the decision, namely, that the new evidence did not merit introduction at this late date. The case continues…

A matter of independence, or public perception… or something in between?

It seems to be something in-between, but something important all the same because the judiciary is not blameless, and the consequences concern the public’s right to know. That “something” stands between the courts and public perception, but the courts or those who speak for them are responsible for the lapse since the public should not be held responsible for what the public cannot know.

Chief Justice Ma framed the problem perfectly when he said the courts are responsible for clarity and the public for accessing the courts’ clear judgements. But he could just as well have given that speech at any time before 1997 because he failed to emphasize the changed nature of the larger frame in which Hong Kong is now embedded.

The sovereign authority overseeing the larger pre-1997 frame was the Privy Council in London. Today it is the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing.

Before 1997, everyone in London and Hong Kong adhered to the same common law principles. Today, Hong Kong courts find themselves in the awkward position of managing a common law system while simultaneously being “bound,” as they say, to enforce Beijing’s mandates.

That transforms Hong Kong courts into sometime enforcers for Chinese Communist Party decision-makers, and the two legal systems are at best uneasy companions.

The Hong Kong courts are also administering justice within a community that has itself been changed by the 1997 transition from British to Chinese mainland rule. Hong Kongers have become voters and the community is far more conscious of human rights and civil liberties than before.

Those changes date only from the 1980s, after Beijing announced its intention to resume sovereignty, and they are generally seen as safeguards, a form of protection against the dangers of Beijing’s rule.

Yet the courts’ conservative defenders use the same arguments today that they might have used before, evidently sincere in the belief that they are protecting the rule of law. They blame the critics without acknowledging the changed political context and the nature of “prosecutorial discretion” that has evolved accordingly.

But the concerned public can hardly be blamed for its suspicions when confronted with the new stricter sentencing guidelines, plus prosecutors who seek re-trials and re-sentencing if convictions and sentences don’t conform to the new political mandates coming from Beijing.

Without more “judicial discretion,” at least in the matter of explaining in plain language that everyone can understand, exhortations to respect the rule of law regardless are likely to fall on deaf ears.