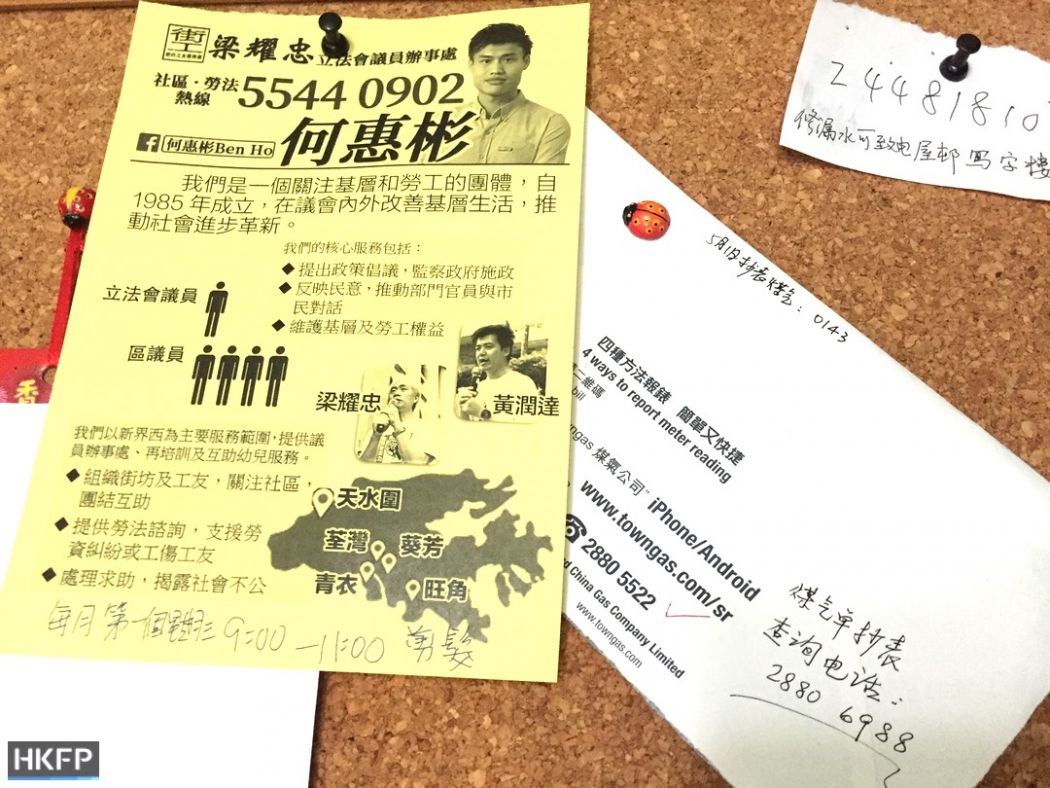

Community worker Ben Ho’s itinerary for the day consists of teaching a class of senior citizens on how to use mobile phones and visits to households in Tin Shui Wai’s public housing estates in the New Territories. The Wongs, an elderly couple in their 60s, warmly welcome Ho into their humble apartment; they have a flyer bearing his face tacked to their notice board.

Ho, 28, works at the Neighbourhood and Worker’s Service Centre, a political party that focuses on grassroots and labour issues. Ho was primarily visiting the Wongs to look at their bathroom ceiling – which was falling apart – and to give them an overview of what the volunteer team would do when they come round to carry out repairs. The inspection could have been a quick five-minute job, but after half an hour of friendly banter it became clear that Ho was deliberately taking his time to keep them company. The couple have lived alone since their son moved out last year.

Ho jokingly calls himself a “part-time grandson” – a reference to part-time girlfriends, young Hongkongers who engage in sex work. But unlike “PTGFs,” Ho does not charge for his services, which range from providing Tin Shui Wai’s senior citizens with guidance on how to deal with labour disputes to taking them to doctor appointments. Recently, he accompanied an elderly lady all the way to Causeway Bay for her cataract surgery, a trip documented by local media outlet HK01.

Given the long working hours and limited size of Hong Kong’s public housing apartments, most adult children often move out once they joined the working force — especially given Tin Shui Wai’s inconvenient location. Others will move out once they start their own family. Ho said some senior citizens project their feelings towards their absent children or grandchildren onto him, while others tell him the story of their lives, especially from when they were younger. He has met the offspring of a Kuomingtang officer, an ex-neon light craftsman and a former maths teacher at a university who is now a social welfare recipient. “These are memories they see as significant, but for whatever reason no one has asked them or given them the opportunity to share.”

Ho’s own time in university coincided with the heat of the anti-high speed rail protests in 2009 and 2010, which he said gave him the impression that everyone cared about society. But he soon realised that most people didn’t pay attention when it came to their own community.

“With major issues and occasions such as the July 1 [democracy protest], June 4 [Tiananmen Massacre commemoration] or expressing our discontent towards the lawmaker disqualifications — thousands, tens of thousands, would hit the streets to protest. But when it comes to the struggles ordinary citizens face or family problems, no one cares,” he said.

So he stepped up.

The silver tsunami

In 2017, around 1.78 million of the 7.4 million people in Hong Kong are over the age of 60, according to census figures. The government’s assistance of senior citizens comes mainly in the form of subsidies — such as the “fruit money” old age allowance, which provides HK$1,345 to any Hongkonger over the age of 70, as well as the old age living allowance and higher old age living allowance for those with financial needs, at $3,485 and $2,600 respectively.

The government also supplies annual health care vouchers of HK$2,000 and vouchers sponsoring care home services to senior citizens. But Mrs Wong said she felt the government was not doing enough for the grassroots elderly population. It can take a long time to book appointments with doctors under the medical voucher scheme, while the voucher amount is scarcely enough to cover expenses when a pair of prescription glasses could already cost them HK$2,000. There have also been numerous cases of participating parties overcharging senior citizens and abusing the scheme, with the Department of Health receiving 72 complaints on the matter last year.

As of May, nearly 40,000 are on the waiting list for subsidised residential care services, with an average waiting time of around two years. The quality of elderly care homes, however, is hit and miss. Three years ago, Ming Pao reported that staff of Cambridge Nursing Home in Tai Po had abused their elderly residents, who were stripped naked in an open area while queuing up for a bath. Ho, too, is concerned that most homes operate as businesses with commercial concerns rather than with the spirit of a good Samaritan.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s policy address last October stated that the priority of the government is now with home care and community care over elderly residential care centres, reaffirming the policy of “ageing in place as the core, institutional care as back-up.” This means that senior citizens could remain in their own residences and the government will mostly deploy teams to provide backup services such as bringing takeaway food to the elderly and transporting them to the doctor.

However, the waiting time for home care services and community care services for the 6,000 applicants on the waiting list can be up to 14 months, according to figures released in May. Ho has also heard of instances where the government would terminate services due to a lack of resources which – to him – defied common sense: “A senior citizen’s health isn’t going to suddenly improve — it will only worsen over time.”

‘City of Sadness’

Ho’s party has a district office located in Tin Shui Wai, giving him a front-row seat to the issues plaguing the elderly population. A decade earlier, remote Tin Shui Wai earned the nickname “City of Sadness” due to a spate of suicides and domestic violence cases. The area is predominantly occupied by new immigrants or working class Hongkongers. With little private housing or middle-class residents with spending power, the local economy never took off or became self-sufficient.

Tin Shui Wai is viewed as an unsuccessful town project and many in the community feel abandoned by the government. On one recent occasion, Ho had to pressure the Housing Authority into tackling the rat infestation problem at one housing estate, after residents counted 45 rodents on a single floor of a block.

Now, the public housing estates are over 20 years old, and their residents – who were middle-aged when they moved in – have joined the elderly population. Young people have moved to the city to work, saving themselves a three-hour commute each day. And families across Hong Kong have shrunk meaning that multiple generations no longer live under one roof. An ageing population has now been left to fend for themselves.

The thought that the couple may continue to live on their own in the years to come worried Mrs Wong. “We’re getting older… I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future.” Given her age, she said, it was hazardous for her to climb up and down to look at the ceiling: “If I fall, it could be big trouble for me.”

She said she had sought the assistance of handymen, but none of them were willing to come for such a minor problem; she also had little confidence in them after witnessing a locksmith charging a neighbour who had forgotten the door key HK$1,000 just to open the door. Without expertise in the area, she preferred to rely on people she trusted like Ho, whom she met at a mobile phone class. “[My husband and I] are not working anymore… and we want to do our best to save money.”

On another occasion, when she wished to replenish the refrigerants for her air-conditioner, she was told by a community worker from her District Council branch that they do not have staff for such matters and to do it herself. “Maybe they mostly sit in the office… they won’t bother with trivial matters like this.”

Ho said he believes the weak community support has to do with the political atmosphere. At the 2011 elections, the incumbent district councillor – from a pro-Beijing party – had run uncontested and hence was automatically elected. There was therefore a lack of incentive to improve community services, Ho said, besides the usual tactics of handing out freebies before elections to curry favour with residents in exchange for votes.

It was pointless to the grassroots and elderly population, he said, “if you give them ten dumplings but their ceiling is still broken… and their washing machine isn’t fixed.” Eventually, residents grow disheartened and they expect less from the party that serves the area, meaning the councillors can afford to do even less, he observed.

“This is a vicious cycle,” Ho said. As councillors cannot gain the trust of the elderly on election day, they have to resort to methods such as writing the candidate number on their palms or bussing them to polling stations, he added, referring to common methods deployed by the pro-establishment camp as reported, for instance, in South China Morning Post in 2015.

In contrast, Neighbourhood and Worker’s Service Centre’s grassroots work has had a limited effect on its election dreams. It always had a weak presence in the political arena, and Ho even referred to the party as really “a labour group that takes part in politics.” Its members have leanings across the political spectrum, Ho said, and some of the volunteers he has worked with even stated explicitly that they wanted nothing to do with politics.

Ho’s efforts may appear admirable, but it is also illogical in the context of politics. “There are those who think it’s stupid — if you’re an assistant of a councillor or a district worker, doing maintenance or repair work for families is crazy… most won’t make the effort just for one or two votes,” he said. A single case may take him four hours or even half a day.

Ho’s philosophy was simple: “If there’s someone in front of you that needs your assistance, and you’re in the position to help, then you should.” Now, taking his lead, other volunteers have joined in the efforts to help senior citizens, and he has also recruited a handful of secondary school students.

Earlier in June, Neighbourhood and Worker’s Service Centre saw a mass resignation after three members of the labour team were fired by Leung Yiu-chung, the party’s only lawmaker. Leung claimed that the decision was a result of the party’s poor finances, but as a labour rights-focused organisation, the exiting members’ claims that Leung was a “unscrupulous employer” would be no doubt come back to haunt him during elections. This, in turn, could further impact the party’s finances, as part of its funding come from wages and subsidies associated with Leung’s seat.

The controversy, coupled with stress and exhaustion from engaging in community work, triggered a crisis of faith in Ho. He began questioning whether his work has any real impact, or if residents saw him as disposable and he had merely been indulging himself this whole time.

But when he gave himself two days off from work to take a breather, he started getting calls and texts from Tin Shui Wai’s residents, who were already wondering where he was. “I’ll keep doing this work for as long as is possible,” he vowed.

As Ho got ready to leave, Mrs Wong confessed that she did not usually follow the news, but was nonetheless aware of the internal shake-up in Neighbourhood and Worker’s Service Centre, and was concerned that Ho’s job was at stake. “We hope you’ll stay and continue to help us here,” she said. “A good lad,” she murmured.

The Wongs names were changed at their request.